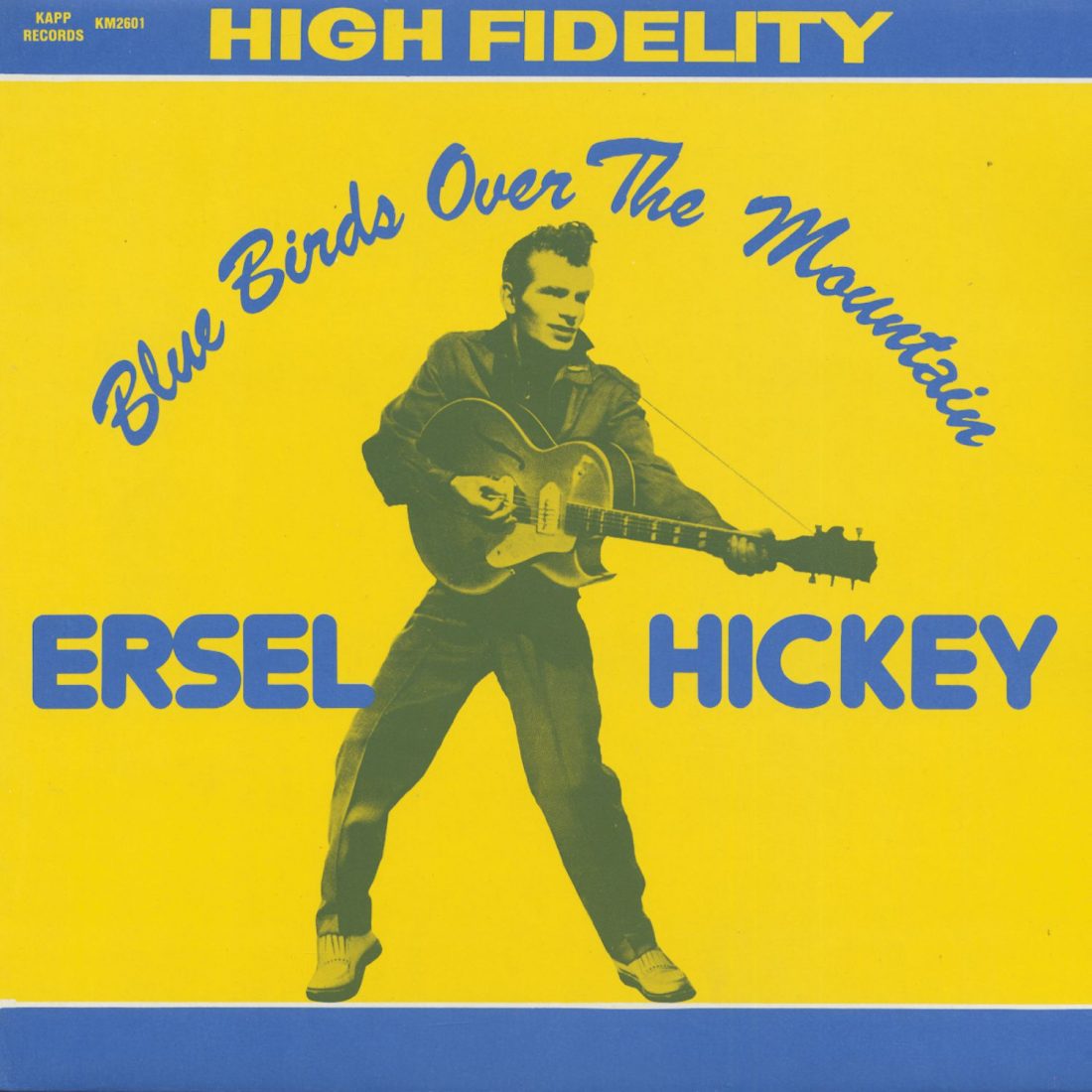

Outside of rockabilly circles, few will have heard of Ersel Hickey, and yet the majority will doubtless have seen his iconic photograph. Vintage Rock tells the tale of the cat behind rock’n’roll’s most famous pose… By Rik Flynn

It was 1976’s The Rolling Stone Illustrated History Of Rock & Roll that transformed a virtual unknown to the eyes of millions. Anyone leafing through that first edition would have immediately been faced with the striking image of an über-cool rock’n’roller in dynamite pose, singled out as the book’s frontispiece. But it wasn’t Elvis Presley, nor was it Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee or Eddie Cochran. In fact, the vast majority of readers would have been completely in the dark as to who he was.

He didn’t even get a mention in the book. The greaser in the photo – collar up, leg elegantly cocked, sporting a perfectly coiffured pompadour and with his guitar thrust provocatively forward – was Ersel Hickey. Until a caption was added to later editions – ‘Ersel Hickey, the personification of early rock’n’roll style’, Hickey was nothing more than a static characterisation of the Big Beat. The image was, and still is, more famous than the man. So who was the guy behind one of the most famous photographs in music history?

Born in Brighton, New York, in 1934, Ersel Hickey got his name from Dr Ersel, the family doctor who helped bring him into this world. It was a rough start for Ersel and his seven siblings. His Irish father died when he was just four years old and his Canadian mother had a nervous breakdown a few years later and was institutionalised. As a result, much of Ersel’s adolescence was spent in and out of foster homes, the circumstances of which endowed the footloose youngster with a passion for doing a runner…

At only 15, Ersel embarked on one such escape when he took to the road with elder sister ‘Chicky’ Evans, a popular burlesque dancer at the time. Ersel clearly found this nomadic life preferable to the alternative, choosing to carry on alone as part of a travelling carnival until he was eventually sent to a home for delinquent boys in Columbus, Ohio.

It was in Columbus that Ersel took to singing; first gospel and then – with 50s superstar Johnnie Ray as his inspiration – leaning more towards a secular sound. It wasn’t long before the stage beckoned and in 1952, Ersel won

both first (solo) and second prize (with a group) in a talent contest in Columbus, scooping $500.

As if losing his father and having an absent mother wasn’t enough, tragedy struck when Chicky died in a car crash. Ersel went back to live with his aunt and brother, with whom he got a job as a locksmith. When Elvis began to make his presence known, a 19-year-old Hickey fell hard for those world-shaking 1954 sides: That’s All Right, Blue Moon Of Kentucky, Good Rockin’ Tonight and, in particular, I Don’t Care If The Sun Don’t Shine, a Mack David tune recorded early on in Elvis’ career. Ersel’s brother booked shows for his talented sibling around Rochester, a stone’s throw from his home.

Now with a local following, Hickey borrowed the funds from his brother to record and in February 1957, with only an acoustic guitar, he cut a simplistic, dog-eared set at Fine Record’s studio in Rochester. The session included a roughshod, yet amiable (abridged) cover of Fats Domino’s recent hit I’m Walkin’, an equally sketchy demo called Street Car Of Desire and two tracks that would make up his eventual debut 45.

Hickey’s primitive debut, You’re No Good!!, was as raw as rockabilly came, but possessed a naïve charm. For the flipside, he took on I Want To Go Where You Go, Do What You Do (Then I’ll Be Happy), a hit for ‘Whispering’ Jack Smith in the late-1920s and a No.75 hit for pop crooner Eddie Fisher in 1955 (likely the version Ersel had heard). Ersel took the name of ‘Mickey Evans’ for the release, a combination of his late sister’s pet name for him and her surname. Fine issued a mere 250 copies and the release disappeared with little fanfare, but it’s a session that hinted at what was to come. An elusive second Fine 45 was supposedly recorded, too, with only one copy rumoured to exist.

At this point, fate intervened. Having seen The Everly Brothers play a local show, Ersel happened to bump into Phil Everly in a local restaurant. “They were performing at the war memorial in Rochester. It was just strange how it happened,” he relayed to WMFU. “He started talking to me and I said, ‘How do you get into the business?’ And he said, ‘Well it takes a good song as a starter. And that’s how it’s done.’ And that night I wrote Bluebirds Over The Mountain. I woke my brother up at 2.30am. I said, ‘Bill, what do you think of this song?’ He said, ‘That’s it! That’s your song.”’

With his newly-penned tune – supposedly inspired by the lyrics to Over The Rainbow – swimming around his head, the young rockabilly boarded a bus to Buffalo the following day. When he alighted that bus after the short trip westwards across New York State, Ersel couldn’t have known that the black-and-white publicity shot that he was about to have taken – dressed to the nines in scarlet jacket and modish slacks – would become one of the most iconic images ever to be attached to rock’n’roll.

Near to Jann’s Casino, a popular haunt on Buffalo’s main street, was the ‘Studio Of The Stars’ owned by Gene Laverne, an exotic dancer and female impersonator who would play a big part in helping Hickey up the ladder. Chicky had had her own promo shots taken by Gene and had advised Ersel to do the same. Laverne no doubt helped position Ersel into that infamous pose, but the full effect of the rakish outfit worn that day is lost.

“The jacket was bright red – Chinese red silk actually. I bought that at a flea market… and the pants were rust coloured,” he told Meredith Ochs. “It was a wild outfit and, of course, the guitar was one of the best ever. Even today, that ES-295 Gibson, the gold guitar, it sells for a huge amount of money and they sell a lot of them because of that picture.”

After Rolling Stone’s Illustrated History…, Ersel’s image was used for anything and everything related to rock’n’roll from pins and badges to T-shirts and posters – Louisville’s Guitar Emporium still use Hickey’s silhouette as their logo to this day. It’s a picture that inspired fans to go the extra mile.

“Recently, I was up in Green Bay, Wisconsin and I did a rockabilly show up there,” Ersel told WMFU in 2002. “They had The Crickets, Jack Scott was there and Charlie Gracie… The fans came up from all over the world. We signed autographs for close to three-and-a-half hours. They even had the shoes I wore in that picture. They manufacture those shoes! And, of course, they had tattoos with my picture on it. So I signed a tattoo and about two hours later, he came back and he had it tattooed right in!”

After that mythical shoot and with local fame, Hickey made the move up the ranks and began to work the clubs and casinos of Buffalo. Soon, Laverne had hooked him up with record exec and composer Mike Corda (Corda also penned tunes and produced for Bill Haley), who became his manager and producer. It was a good association for Hickey. Sensing a hit, in November 1957, Corda booked his new hopeful into the modest National Studio in New York to record a demo of Bluebirds… With his new manager on bass and guitarist Jimmy Mitchell on hand, Bluebirds… was cut together with flipside Hangin’ Around, rush-written in 15 minutes in the studio.

Influential Buffalo DJ George ‘Hound Dog’ Lorenz often took a punt on lesser-knowns and gave Ersel’s demo some airplay on his popular WKBW show. Epic Records’ boss Joe Sherman took note and in January 1958, purchased the tapes.

It was while at a show in Niagara Falls that Ersel heard word that Epic Records had chosen to offer him a contract.

So confident was Sherman that he issued the untouched demo as a 45 in January of the following year.

On Valentine’s Day 1958, Ersel performed the song on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand and in March, for The Dick Clark Saturday Night Beechnut Show, a huge show that went out on ABC. Ersel was clearly a whirlwind to watch.

“I shared the stage with Ersel more than once,” wrote friend Wes Bryan. “Believe me, the girls went crazy for him and those shakin’ legs of his.”

Aside from scoring a lucrative publishing deal for Ersel, the record would go on to top the charts in New York for a five-week stint. It went national, too. At No.75 in the Hot 100, it was Hickey’s sole Billboard hit, thanks in no small part to the TV exposure and the fact that distribution went through Columbia, the biggest distributer at the time. Jukeboxes played a big part, too.

“I could go into the South and I might not be getting play there, but I would be on the jukeboxes,” Ersel told Ochs. “You could get good action on your records… and they covered all the jukeboxes.” The single also made a big impression on his peers. Frankie Sands released a version (Imperial, 1958), as did Ritchie Valens (London, 1959), and Ronnie Hawkins, whose 1965 ballad version made the Top 10 in Canada. At only one minute and 20 seconds, it was a work of rare quality – and one of the shortest hit singles in history.

1958 was a busy year for Ersel. Eager to capitalise on the success of Bluebirds…, Sherman booked a May session at Columbia’s New York studio to record a second single for July release. With help from New York sessioneers including Billy Mure and jazz drummer James ‘Osie’ Johnson, Ersel was cooking on all cylinders.

Goin’ Down That Road was a fervent rocker with a rousing hook of ‘Boom-chicka-boom-bop-bop’. It’s now a much-loved staple. Flipside Lover’s Land was solid mid-tempo rockabilly. An unfinished third (church) song, Due Time, revealed Ersel was reaching the ears of the big league.

Colin Escott writes in the liner notes to Bear Family’s Bluebirds Over The Mountain compilation that Hickey played it to Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, who then adapted it for Wake Me, Shake Me, a No.51 hit for The Coasters in 1960.

On 23 July 1958, Ersel returned to American Bandstand to sing both sides of his follow-up, but even with the exposure, this time it was lost to the ether.

Hickey’s recording continued in earnest and a return to National Studio in October with musician and arranger Al Caiola (and Mike Corda) turned out both teen pop (Wedding Day) and clean-cut rockabilly (You Never Can Tell). Both You Never Can Tell, written with Blueberry Hill co-writer Al Lewis and another track, I’m Ready were offered to Ersel via demos sung by Bobby Darin, but it seems he chose the wrong track. While You Never Can Tell charted in LA, Detroit and Chicago, I’m Ready was picked up by Fats Domino, whose bounding boogie-woogie made the Billboard Top 20.

Ersel returned to New York in March of 1959 to cut his next two 45s. Shuffling rockabilly You Threw A Dart

(his first record to land a UK release) and I Can’t Love Another marked an ultimately unsuccessful direction for Hickey, ushered in with the new decade. “Epic and Kapp often tried to cast Hickey in the teen-crooner mould,” writes music historian Greg Adams, “even though his husky voice and its limited range resembled Fabian or Gary Shelton far more than Bobby Vee, with whom he competed on a string-laden version of What Do You Want?”

Ersel ended the year with another Dick Clark appearance and while it’s unclear what songs were performed, it’s likely he peddled that version of What Do You Want? (a UK No.1 for Adam Faith). Ersel wasn’t a fan, plus only had one day to rehearse. It showed. A far cry from the primitive sounds of his early strikes, it too died a death – despite Epic’s claim in Billboard that it was “starting to move”.

Hickey’s closing statement for Epic was cut in April 1960 and, while still squarely aimed at the teen pop market, Stardust Brought Me You at least gave a nod to his humble acoustic beginnings.

Big changes came when Sherman (now his manager) secured a new contract with Kapp. Not only did Hickey record his two sole Kapp singles at the infamous Bradley Studio in Nashville, but the city’s elite session stars were in attendance, including guitar ace Grady Martin and pianist Floyd Cramer.

The musicianship shines through on the woozy pop of Teardrops At Dawn and Lips Of Roses, both cut over two days, together with B-sides and some unissued tracks. Strong swooning pop it may have been, but it was still far from Ersel’s rockabilly prime. With no chart success, Hickey’s brief tenure at Kapp expired – as did his six-month association with Sherman.

With fewer bookings, Ersel began writing for other artists. Jackie Wilson (Ersel’s favourite singer) released Bad News Travels Fast (Brunswick, 1962), while LaVern Baker cut A Little Bird Told Me So for her 1963 LP See See Rider. The following year, Hickey was married and settled in New York. It was an opportunity to further flex his songwriting muscle.

He shopped songs at the Brill Building and pitched to Johnny Cash, losing out solely because of conflicting publishing interests (“He loved the songs, but they never got recorded.”) He even got close to Elvis. “I wrote a lot of things for Elvis,” said Hickey. “They used to buy them over at Hill & Range [Elvis’ then publisher], but I never got an Elvis record.”

In 1962, Hickey cut the excellent pop-rocker Upside Down Love for Apollo, and Eddie Miller’s Toot Records put out a succession of his music later in the 1960s, but the glory continued to fall to others. In 1964, Don’t Let The Rain Come Down (written with Miller) went Top 10 for The Serendipity Singers.

“I wrote the song for Jimmie Rodgers,” Ersel told WMFU. “I took the song to him one night and I said, ‘I wrote this song for you. I don’t know if you’d like it or not, but I’ll drop back…’ So the next night, I came back and said, ‘Did you like the song?’ And he said, ‘Like the song? I recorded it this morning at 11 o’clock!’ So that’s how fast those records were done in those days. And then, of course, The Serendipity Singers heard the record on an album and made a single out of it.”

Another big success came in 1968, when The Beach Boys released their version of Bluebirds Over The Mountain

(it also appeared on their 1969 album, 20/20) and purchased the publishing rights – a lucrative arrangement for Ersel. “That’s a psychedelic version,” he told Meredith Ochs.

“I expected something different, but it was fine. It sold very well and hit the charts. We’re on 17 albums, so I’m very happy with that!”

A string of independent releases saw Hickey through to the mid-1980s. Having stormed Viva Las Vegas in 2002 and with more plans to tour, he sadly died in 2004 aged 70. Notoriety may have arrived under strange circumstances, but Ersel Hickey was indeed the personification of early rock’n’roll.

With thanks to Louisville News, The Rockabilly Hall Of Fame and WMFU