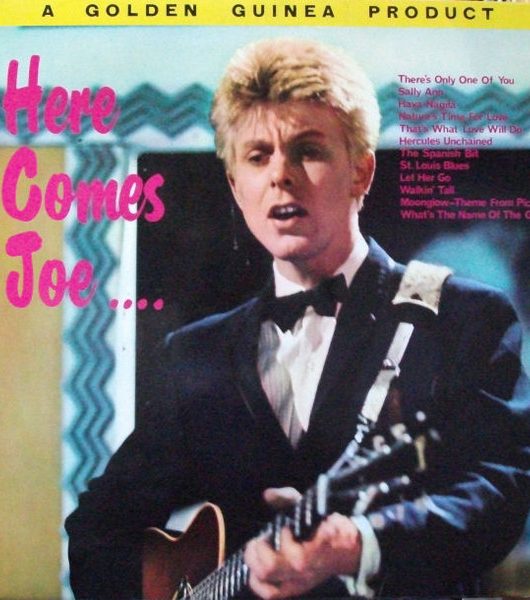

Story Behind The Song: Cliff Richard and the Drifters – Move It

By Jack Watkins | September 27, 2025

Some people regard Cliff Richard and the Drifters’ Move It not just as the first true British rock’n’roll recording, but also the greatest. Here Vintage Rock traces its creation…

It’s often said that the great thing about rock’n’roll is its spontaneity. Many of its most celebrated songs were written or recorded off the cuff. Jess Stone rustled up Shake, Rattle & Roll under orders from Atlantic boss Ahmet Ertegun to knock out an up-tempo number for Joe Turner. Little Richard’s Tutti Frutti was hurriedly extemporised almost in desperation when a debut session for Specialty wasn’t delivering the anticipated fireworks.

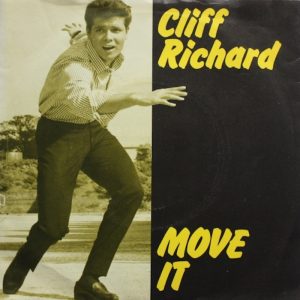

Shakin’ All Over was another spur-of-the-moment job, written by Johnny Kidd, and Brian Gregg and Alan Caddy of The Pirates, sitting on Coke crates in the cellar of a Soho coffee bar the night before a session, and only intended as a B-side. As for Move It, widely acclaimed as the first authentic British rock’n’roll record, and for some people the finest, it was penned by the Drifters’ rhythm guitarist Ian Samwell on the top deck of a Green Line bus on his way to rehearse at his mate Harry Webb’s house in Cheshunt, Hertfordshire.

Webb’s initial love of rock’n’roll was fired by hearing Heartbreak Hotel, which had introduced Elvis Presley to the youth of Britain in the spring of 1956. His father brought him his first guitar later that year and by the time he’d caught Bill Haley and His Comets’ show at the Regal, Edmonton, in North London, in March 1957, he had a raging desire to perform. He formed a vocal group the Quintones.

On The Move

Then, still only 16, and with skiffle all the rage in the UK, he joined the Dick Teague Skiffle Group, before breaking away with Terry Smart to form a band, which placed more focus on rock’n’roll. Eventually settling on the name of the Drifters – unaware of the existence of the supreme American vocal group of that name – by early 1958 they were playing clubs and pubs in North London, before graduating to the 2i’s in the West End. It was here they met up with and acquired guitarist and embryonic songwriter Samwell.

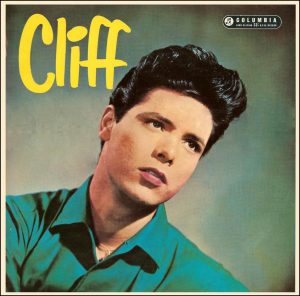

It was Samwell, when it was suggested that the charismatic Webb needed a more attention-grabbing stage name, who came up with ‘Cliff Richard’ – ‘Cliff’ for the rock-like connotations, and ‘Richard’ in part tribute to Little Richard.

Photos show that Samwell and Smart were two nice young lads, but Cliff had the pout and presence to draw screaming hordes of girls to the band’s shows. A rough round the edges demo of Lloyd Price’s Lawdy Miss Clawdy, owing everything to Presley’s version, and of Jerry Lee Lewis’ Breathless, executed above the old HMV shop in Oxford Street was useful enough to gain the ear of Norrie Paramor.

The experienced EMI A&R man brought them in for an audition. He later remembered that they played so loud the walls of the old building seemed to tremble. He followed up by booking the band for a three-hour evening session in EMI’s celebrated Studio Two in Abbey Road on 24 July 1958. It was decided that the two songs to be laid down were Samwell’s Move It and a track the middle-aged Paramor had in mind as the A-side, Schoolboy Crush. This excruciatingly bad song had originally been done by the American artist Bobby Helms and recently released as the B-side to his Borrowed Dreams, a minor hit on Decca in the States.

Rough & Ready

Paramor would prove a great support to Cliff across his career, but his heart was never in rock’n’roll. He’d intended to use the Ken Jones Orchestra, who’d backed Marvin Rainwater on his recent Top 20 UK hit I Dig You Baby, recorded in the same studio, but Cliff insisted that they needed to go with a small group sound. Paramor did lay on a backing vocal group for Schoolboy Crush, the Mike Sammes Singers, as ubiquitous on British recordings around this time as the Anita Kerr Singers were in Nashville.

Paramor knew Schoolboy Crush was a mediocre song, but his ear was not attuned to the youth market and, hard as it seems to credit now, it would take him some time to recognise that Move It, with its rough edges, was a stronger side than what he would regard as the more polished and professional Schoolboy Crush.

Along with Cliff, the only Drifters to appear on the session were Samwell on rhythm guitar and Smart on drums. They were augmented by the experienced sidemen Frank Clark on upright bass, who had played in the Beryl Brydon skiffle group, which had also featured Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies, two luminaries of the upcoming UK blues boom. Electric guitarist Ernie Shear, who had also dabbled in skiffle with the Hallelujah Skiffle Group, twanged to order on successful British rockin’ covers like Tommy Steele’s Come On Let’s Go and, alongside Bert Weedon, on Marty Wilde’s cover of Endless Sleep.

First up on the session was Schoolboy Crush. The only thing to recommend it was that it had been part-written by Aaron Schroeder, co-creator of several Presley songs, including the exhilarating Any Way You Want Me (That’s How I Will Be) and Got A Lot Of Livin’ To Do, as well as Glad All Over for Carl Perkins. But while Helms’ original of Schoolboy Crush was painful enough, the Drifters’ version was at least as bad, featuring possibly the most annoying whistling and pit-a-pat drumming ever heard on wax.

Crushin’ It

If it was an attempt at mining the same territory as A White Sport Coat which, whether performed by Marty Robbins or Terry Dene, was actually a charming, well-constructed song, it didn’t. Viewed through the prism of 60-odd years of rock, this calculated bid to ingratiate itself to teen tastes is quite offensive.

Luckily, it was to be overshadowed by Move It. Although the senior pop engineers at Abbey Road during this period were Peter Bown and Stuart Eltham, by the time they had finished recording Schoolboy Crush, there were only 40 minutes left on the session’s allotted three-hour allocation. With Bown departing early because he had tickets for an opera performance, a young engineer Malcolm Addey, recently hired to assist Bown and Eltham, was left at the controls.

This proved significant. Addey was just a few years Cliff Richard’s senior. No more impressed with Schoolboy Crush than the band had been, whereas the EMI rulebook at the time had strict stipulations about how loud recording levels should be, Addey simply recorded what he heard coming though the speakers. Disregarding the accepted noise levels gave a distinctive echo effect, a trace of distortion lacking in British rock’n’roll up to that point, when convention dictated a flatter sound to balance out the instruments. There was an edge to Move It that was quite unprecedented. Remarkably, recorded on a single-track tape, with no capacity to overdub or remix, it only took two takes to nail the number.

Moody & Broody

Although Samwell had devised the guitar licks and fills that became the song’s signature, he recognised he was not skilled enough to produce these effects on tap in the studio, and so simply imparted his ideas to Ernie Shear, while playing rhythm guitar himself. Somewhat bafflingly, Samwell wasn’t pleased with some of what he felt were Shear’s “Bill Haley-like fills”, but as it was destined to be the B-side, raised no complaint. “I think we just talked about it in the studio and it developed,” said Shear, quoted in Steve Turner’s Cliff Richard: The Biography. “It was really a busking session for us even though we read music.”

Lacking a solid-body electric guitar, Shear played a Hofner Acoustic with a DeArmond pick-up pushed up to the bridge. “I wanted the toppiest sound I could get.” Samwell’s grinding, bottom-oriented rhythm guitar rumbled away in menacing support, perhaps the most suspensefully exciting moments coming six seconds in, and again at one minute 20 seconds, to the track, when the two guitars briefly combine to play the riff together. A couple of decades later, Carl Perkins, quoted in Steve Turner’s biography, would say that its sound “could have been made in Sun Studios in 1954. It’s basic rockabilly music. That guitar is doing what we did. He’s got some echo and he’s working on more than one string. He’s getting three of the bass strings and he’s doubling up from the bottom. That’s very good.”

Not to be overlooked is Cliff’s vocal. The subsequent direction of his career meant that his work as a rock’n’roller has been underrated. Although on early TV performances he would overdo the moody, broody sub-Elvis posturings, he had his own mid-Atlantic sound, very different from the London twang of Tommy Steele, Wee Willie Harris and Johnny Kidd. As with Billy Fury, Elvis was a key influence, but he lacked the Liverpudlian’s thrilling, quavery fragility. Cliff was a hybrid, with something of the warm, wholesome appeal of Ricky Nelson. It was more than good enough for Move It.

Move It And A-Groove It

As with all early rock’n’roll, Move It wasn’t exactly deep and meaningful, although it did stem from strong feelings. Samwell described his creation as having “all the magic of a first-time hit, without any experience behind it, not like the way I write numbers now,” in Bob Ferrier’s The Wonderful World of Cliff Richard (1964). “I break them down, I play songs to people. But then I didn’t know, I just wrote the song. I saw the Melody Maker front page, it said something like rock and roll is dying. I thought, they’re joking because it was sort of rampant at the time, but they were always saying things like that.” So Samwell wrote the conversational line: “They say it’s going to die but let’s face it, they don’t know what’s going to replace it.”

Samwell also later recalled on his personal website that he designed Move It to be as American as possible, and that it was the result of “everything I had ever learned ranging from Gene Autry’s campfire songs to Chuck Berry’s splendiferous observations about teenage America.” Terms long in use by hip Americans like ‘pretty baby’, ‘honey’ and ‘groove it’, dotted the lyric sheet.

For a while, Norrie Paramor persisted with his intention to release Schoolboy Crush as the A-side. It wasn’t until an EMI record plugger gave a copy to television producer Jack Good, who immediately latched on to Move It – a reaction echoed by a similar response from Paramor’s young daughter that he realised his misjudgement.

It’s Called Rock’n’Roll

Move It swept up the UK hit parade, stalling only at No.2. As Pete Frame wrote in The Restless Generation, “even the rock’n’roll cognoscenti, those purists who refused anything non-American on principle, had to admit that this was a fantastic record.”

It also had a visual impact in those more innocent times. When a ‘smouldering’ Cliff performed it on Jack Good’s new youth music show, Oh Boy!, the Daily Mirror asked: “Is this boy too sexy for television?”

The impact of Move It may have been relatively short-lived, but Howard Massey, in his The Great British Recording Studios, quotes John Lennon stating that “the first English record that was anywhere near anything was Move It by Cliff Richard, and before that there’d been nothing.”

Budding young British musicians of the time certainly took note. Led Zeppelin included the song on a compilation CD which paid tribute to their many influences, The Music That Rocked Us. A young Freddie Mercury, tonally quite close to Cliff Richard, imitated some of his mannerisms, and Motörhead’s Lemmy was apparently inspired by seeing him perform on Oh Boy!. Sting has said that Cliff was technically the most accomplished of the British singers.

If, in the late 1950s, “America had teenagers and everywhere else just had people,” as Lennon said in an interview included in The Beatles Anthology, 18-year-old Cliff and the Drifters, and most especially Move It, demonstrated that it didn’t have to be that way.

Visit the official Cliff Richard website here

Read More: Rock’n’Roll Heroes – The Shadows