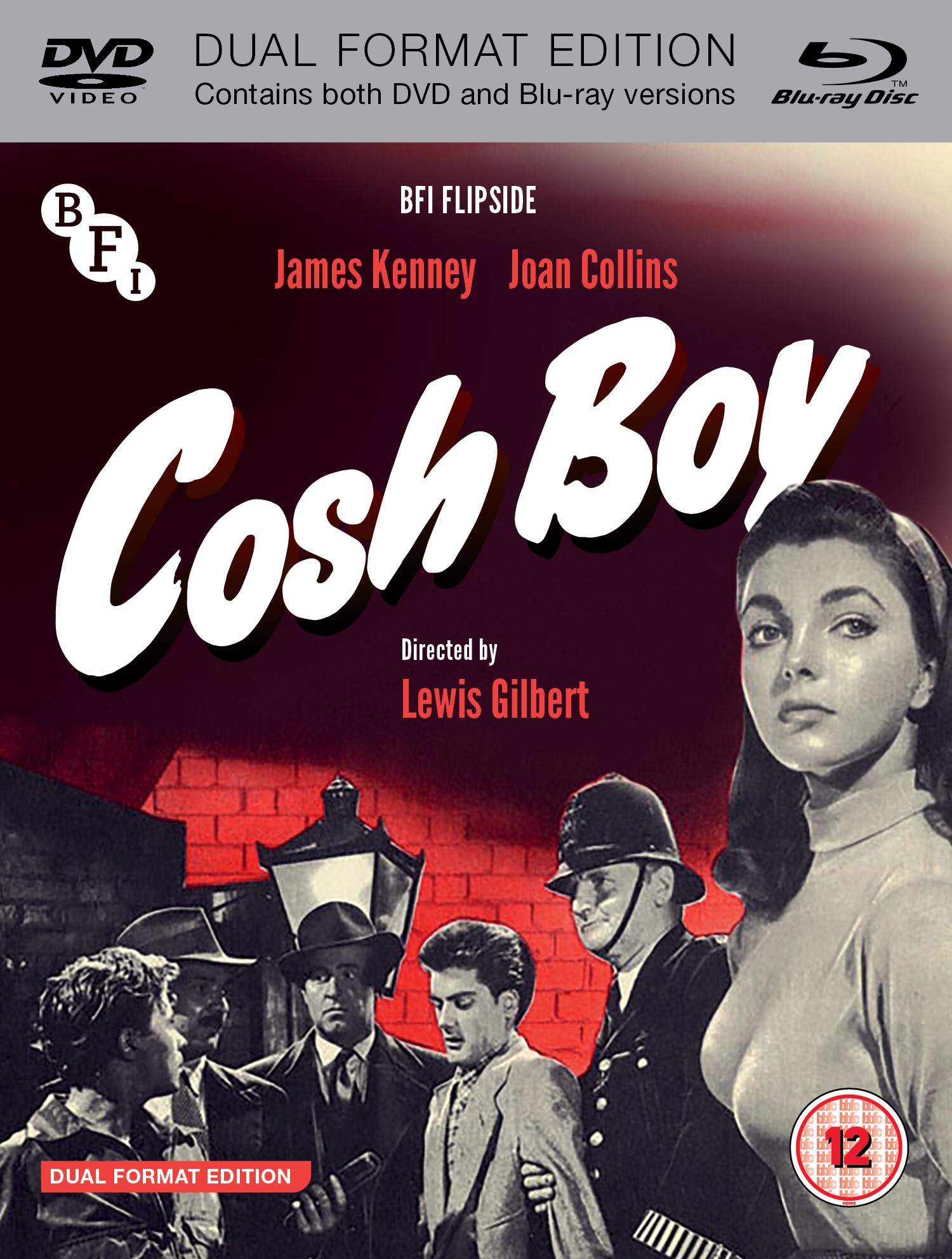

Only the second British film to be given an X certificate on its release in 1953, even that didn’t stop critics calling for Cosh Boy to be banned. Now available on DVD and Blu-ray from the BFI, it offers a fascinating insight into the way middle Britain was reacting to the rising youth phenomenon of the 50s.

By Jack Watkins

Teddy Boys have a special status in the story of rock’n’roll. They brought a uniquely British stylistic panache to the scene in the 1950s and remained loyal to the music in the 1960s when others were deserting it. They made a comeback in the 1970s, and even if it sometimes seemed like a bit of a parody of the good old days, it was good to see them about. There was some argy-bargy with new fans of rockabilly during that time, another unfortunate example of the tendency of lovers of pre-flower power era music to shoot ourselves in the foot when in reality we’re all in it together, but Teds have kept going right into the new millennium. That’s what you call loyalty and riding out the storms.

Yet the fact is that, for broader society, the sheep-like followers of conventional hypocrisy, the Ted has long been a dirty word. How far back the distaste goes is reflected in Cosh Boy, which has just been remastered and released by the British Film Institute on DVD and Blu-ray. The film was first released in 1953. That date is a reminder that Teds predated rock’n’roll and that, although they took Bill Haley to their hearts, before he and Elvis Presley came along, they were listening to big band swing, smaller jazz combos, belters like Frankie Laine and Johnnie Ray, as well as crooners and cowboys, the go-it-alone types all conveniently wiped out of the picture by subsequent generations of music writers, and even sometimes by hardcore rock’n’roll fans.

Shock to the system: Cosh Boy was released in the United States as The Slasher

Cosh Boy is no Ted-fest, however. The name isn’t used, the term ‘cosh boy’ being an alternative term which was often favoured by the sensationalist press at the time. The music Teds loved plays no part in the film, other than some tame jazz at a youth club, but the film is remarkably frank for its period in the teenage issues it covers, including pregnancy, abortion, crime, violence and lack of respect for adults.

This wasn’t the first British film to cover the violent youth, the troubled soul on the edge of society. You could argue the first and greatest British outsider movie was the Boulting Brothers’ adaptation of the Graham Greene novel Brighton Rock, released in 1947. Although it softened Greene’s totally heartless ending, the film drew a menacing performance from Richard Attenborough as the boy gangster Pinkie, had stellar support from hardnut character actor William Hartnell, and included scenes of razor-slashing violence from the notorious Brighton race gangs.

Then there was the Ealing crime thriller The Blue Lamp (1950), which shocked the nation by having the pipe-smoking, begonia-growing, community-minded PC Dixon of Paddington Green, played by the ever-excellent Jack Warner, gunned down by panicky, small-time hoodlum Tom Riley (Dirk Bogarde), just over half-way through the film. Beyond the fact that killing a policeman was well beyond the pale in those days, you definitely weren’t supposed to shoot Jack Warner, a national treasure if ever there was one. Audiences were left speechless. But as well as car chases around the enviably uncongested streets of Paddington and Ladbroke Grove and exciting scenes at the lost, lamented White City dog track, there are also exterior and interior shots of the Metropolitan Theatre, popularly known as “The Met,” on the Edgware Road. This was to be the last of the great London music halls to survive into the rock’n’roll era, hosting gigs by skifflers like Chas McDevitt and The Vipers, and early British rock acts like Tony Crombie And His Rockets, Wee Willie Harris, and Terry Kennedy’s Rock’n’Rollers, which featured seminal figures like drummer Clem Cattini and bassist Brian Gregg, and which morphed into Terry Dene’s Dene Aces. The theatre was finally demolished in 1963, ironically to make way for the new Paddington Green police station.

Both Brighton Rock and The Blue Lamp became revered British films, a fate that never happened to Cosh Boy, a fact that makes its arrival on disc something to be welcomed. The film was based on Bruce Walker’s West End play Master Crook which, strangely, given the subject matter and the tendency of critics of the time to be outraged by the smallest sign of anything pushing against the barriers of what they considered acceptable to polite society, aroused little controversy. Even so, as cinema censorship was even stricter than that of the stage, the swearword “bloody” had to be changed to “ruddy” for the movie, and the description of lead character Walshy, an arrogant chain-smoking thug who bullies his mates into gang assaults and street muggings, as a “little bastard” had to be watered down to “brat”. Use of the razor was forbidden, although Walshy is seen to try to use it at the film’s climax, while the coshings could only be shown in long shot.

Youthful stars: Cosh Boy stars James Kenney and Joan Collins

Even after all that, Cosh Boy was deemed provocative enough to merit becoming only the second British film to get the X certificate, introduced in 1951 to allow the licensing of films for viewing by adults. To begin with it had been mainly applied to foreign films, which tended to contain more sex and violence. The first British film to get one, Women Of Twilight, had been released the year before, and came from the same independent filmmaking company – Romulus Films – that would make Cosh Boy. One of the co-producers Daniel M. Anger was the son-in-law of Vivian Van Damm who ran the celebrated Windmill Theatre in London’s Piccadilly. The two films also had the same director, Lewis Gilbert, who would have one of the longest careers in British film, first appearing on screen as a child actor in the 1930s, working for the RAF film unit in the Second World War, and directing one of the most successful British war films of the 1950s, Reach For The Sky. He went on to direct three James Bond movies (You Only Live Twice, The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker), and was still making films in his eighties. He died aged 97 in 2018. As Gilbert would say in a late interview, today you could show Cosh Boy to 10-year-olds, but the timing of its release was definitely unfortunate because, between the start of its production and the date of its first screening, Britons had been closely following the Craig and Bentley murder case, in which two teenage cosh boys, or Teds, had shot and killed a policeman while carrying out an attempted armed robbery at a south London warehouse. Christopher Craig, who had pulled the trigger, was underage, and eventually ended up serving 10 years in prison, while the older, but mentally unstable, Derek Bentley, was hanged.Craig was apparently steeped in American gangster movies, and there were obvious, if unintended parallels between the case and the Cosh Boy storyline, with gang leader Walshy essentially behaving like a small-time mob leader, intimidating his mates into carrying out the coshings at his instigation, while watching from the sidelines. The first screening of the film took place just a week after Bentley’s execution, and the trial and lead up to the hanging had been a major story in the press for months.

James Kenney, who’d played Walshy in the play, repeated the role on screen. The character, at 16, can be seen as a development on from the spiv type, who had come to the fore in the Second World War and the subsequent years of rationing, which went on well into the 1950s. Spivs tended to be dapper, cheekie chappie types with a gift of the gab, however, as personified by Private Walker (James Beck) in Dad’s Army. They needed to cultivate an air of surface respectability to do business with ordinary people. But the cosh boys, or Teds, while they were extremely stylish, were essentially a youth phenomenon. Disgusted and bored by their surroundings, the gang warfare and assaults on

members of the public arose out of this. They tried to find meaning by developing their own dress code, and behaving differently to the stern, dull adults who tried to dictate to them.

Walshy is a classic type. He is constantly pulling out a comb to use on his greased back, thick wavy hair, quite long in contrast to the regulation short back and sides of the male adults in the film. When he stands in front of a mirror to comb his hair in front of what he calls his “silly old cow” grandmother, she says: “Would you like me to lend you a couple of hair pins?” Her attitude to his preening typified the way the older generation saw this obsession with appearance as unmanly.

However, there’s almost zero effort made by the script to take an interest in Walshy’s psychological make-up. While American rebel movies of the 1950s offered thoughtful studies of juvenile delinquency like The Wild One (banned from being screened in Britain until 1967), Blackboard Jungle and Rebel Without A Cause, conformist-minded Brits clearly couldn’t deal with the idea of bolshy youths. Walshy is depicted as a character without any redeeming features. There’s no attempt to understand his hyperactive insecurity, in fact the film starts with a caption describing the cosh boy as “an enemy of society at sixteen” and that the film is “presented in the hope that it will contribute to stamping out this social evil.” This essentially seems to amount to him being given a good thrashing by the boyfriend of his mother, who Walshy regards as a “big Canadian slob.” Ironically this character and the officials in the film are so stiff, modern viewers will probably end up half sympathising with the obnoxious Walshy anyway.

The film certainly is of interest in the 50s style department. Walsy’s jackets have padded shoulders, the trousers have large turn-ups, and he wears a bomber jacket with a flick knife in the front pocket. Jenny Hammerton, a film archivist who has contributed an essay, Teds And Fashion, to the booklet accompanying the BFI disc, wonders if Walshy’s style influenced the wardrobe department of Rebel Without A Cause, in which a similar look marks out James Dean: “In that instance, the protagonist wears a red bomber, the collar always turned up, that has become the iconic jacket choice of the wannabe rebel. Watching Cosh Boy, it seems Walshy beat him to it a few years earlier, refining the Brando look from A Streetcar Named Desire (1951).”

Hammerton also notes Rene, the girlfriend he treats so cruelly, played by a young Joan Collins on loan from Rank Studios, starts off in a demure cotton dress and an Alice band in her hair. But after she starts going out with Walshy, this is ditched for a big skirt, brassy earrings and a turned-up lace collar, “all costume signposts that this good girl has gone bad.”

Two generations: Joan Collins (left) went on to become an international star and Hermione Baddeley was a much-loved British actress who had also starred in Brighton Rock

When Cosh Boy came out critics reacted with fury. Milton Schulman of the Evening Standard wrote, “The cosh boy can glow in the admiration of his fellow morons. He can have the prettiest girl in the district. He can wear ridiculous drape suits and clownish ties. He can go on coshing merrily soothed by the assuring words of one of the boys in this film: ‘The law don’t worry me. I’m under age.’”

Even when its certificate was put forward for a possible change to an A certificate by the British Board Of Film Censors in 1961, the original X-rating was upheld, the Board’s secretary John Trevelyan, maintaining that “however detestable the boy may be to adults, impressionable young people might find a false sort of glamour in his defiance

of authority.”

Posterity hasn’t turned Cosh Boy into a great film, but it’s full of interest for those of us fascinated by the culture of the 1950s. Much of it was filmed on location among the still-bombed-out wartime ruins of Hammersmith and Battersea. You can see Hammersmith Bridge in the opening coshing scene, and Leamore Street, arguably the eeriest road in London, where Walshy lives with his mum and gran in the basement flat of a Victorian terrace near the railway bridge, is still intact today. Judge for yourself whether Walshy had any motive to carry on the way he did, or all he ever needed was a damned good thrashing.

No holds barred: The film was ahead of its time in its frank depiction of unmarried teenage sex, pregnancy and abortion

TEDDY BOYS

A glimpse into a lost world

Among the special features on the Cosh Boy disc is an eight-minute film originally shot for ITV’s This Week programme in 1956, following “working class west London lad” Mike Wood, a proud Ted, as he talks about his lifestyle. If you think today’s TV presenters are a bunch of mugs, totally unrepresentative of modern Britain, have a gander at interviewer Michael Ingrams. When quietly spoken Mike talks about his desire to make some money if he can find the means, Ingrams asks him if that would include robbing a bank? Mike just smiles at the patronising little doughnut. At one stage, he points out that the only violence he was ever involved in was during a stint in the army. The film starts with Mike and his mates, all decked out in drapes, cravats, bootlace ties etc, being turned away from a club just for being Teds. Mike certainly seems a pretty harmless sort of a bloke. He pays £2 a week for his bedsit in Hounslow West. “I’m very particular about my clothes,” he says, lovingly slipping them off the hangar on the door. “I pay a lot of money for them.” His brain’s sharp too. “The only thing I believe in is what I can see with my own two eyes.” He seems more like someone you can imagine having a talk to today than Ingrams, the apparent voice of middle class England, though you might draw the line at spending one and a half hours in the barber’s chair, and paying three guineas to get your hair permed in the latest bebop style. Then he’s off for a night’s dancing to jazz at the Flamingo Club, Soho, played by The Tony Kinsey Quartet. Now there’s one in the eye for the know-it-alls who thought music for youngsters only started with Elvis Presley.

BFI FLIPSIDE

More gems from Britain’s cultural past

The BFI says its Flipside series is “dedicated to rediscovering the margins of British film, reclaiming a space for forgotten movies and filmmakers who would otherwise be in danger of disappearing from our screens forever. It is a home for UK cinematic oddities, offering everything from exploitation documentaries to B-movies, countercultural curios and obscure classics.”

The BFI says its Flipside series is “dedicated to rediscovering the margins of British film, reclaiming a space for forgotten movies and filmmakers who would otherwise be in danger of disappearing from our screens forever. It is a home for UK cinematic oddities, offering everything from exploitation documentaries to B-movies, countercultural curios and obscure classics.”

Apart from Cosh Boy, other dual format releases have so far have included the likes of Expresso Bongo (1959), the stage satire of the late-1950s music business which was adapted for the big screen as a vehicle for Cliff Richard and The Shadows; London In The Raw, a warts-and-all documentary from 1964 about London’s nightlife; and Beat Girl (1959), which sets late 1950s youth rebellion against a Beatnik backdrop, and features the debut film appearance of Adam Faith (“Drink’s for squares, man.”). Cosh Boy is available on DVD and Blu-ray from the BFI shop for £14.99. Go to bfi.org.uk/dvd-blu-ray/bfi-flipside for more info.