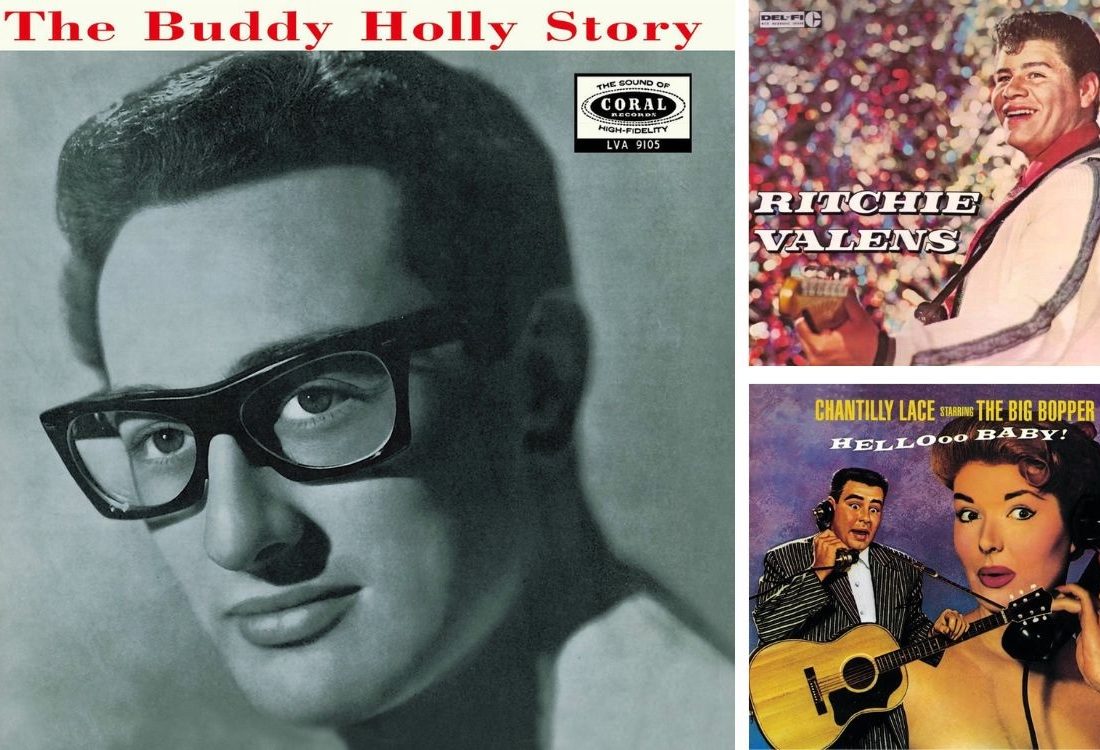

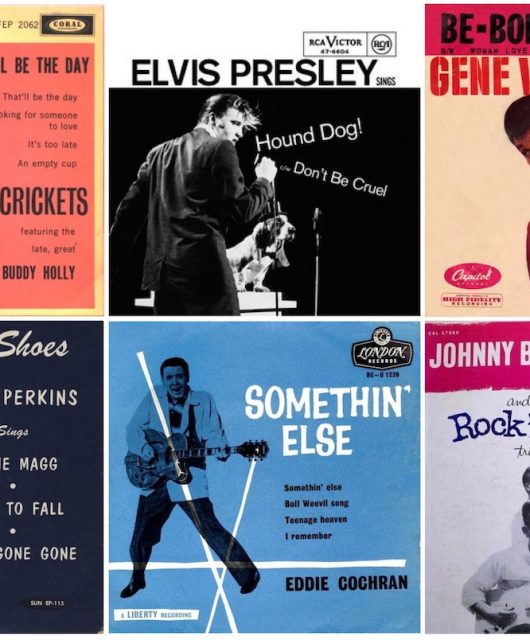

When the rock’n’roll pioneers Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and JP Richardson, aka The Big Bopper set off on a chilly tour in January 1959, no-one suspected it would spell the end of an era and The Day The Music Died...

Words by Randy Fox

On 3 February 1959, Jerry Dwyer’s small plane left the runway of the Mason City, Iowa airport. It was a clear, beautiful Tuesday morning, but Dwyer was on a grim mission. Filled with foreboding, he immediately began scanning the ground below him. A little over eight hours earlier, slightly before one o’clock in the morning, Dwyer had watched a Beechcraft Bonanza owned by his charter flight company depart from the same airport.

The small, four-seater plane was piloted by 21-year-old Roger Peterson, and carried three passengers – rock’n’roll singers Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and JP Richardson, aka The Big Bopper. After leaving the field, the plane levelled off and made a 180 degree left turn, heading to the northwest and its planned destination of Fargo, North Dakota. The musicians were due to perform in nearby Moorhead, Minnesota on the evening of 3 February, and the plane had been chartered to avoid a long, cold and tedious bus ride over icy roads.

Despite moderate wind gusts and snow, the takeoff was flawless. Dwyer watched the tail light of the plane as it receded from sight. About four miles from the field, the plane appeared to descend, almost as if heading for a landing, but given the snowfall and the angle of the turn, that apparent descent was surely an optical illusion.

Winter Dance Party

By daybreak, Dwyer was less sure it had been an illusion. Shortly after the plane departed, he had attempted to reach Peterson by radio, without response. The radio silence continued throughout the whole night. By the next morning, Peterson was sure something was wrong. The plane had not arrived in Fargo, and an alert was issued for the missing aircraft. Taking matters into his own hands, Dwyer decided to follow the most likely flightpath and see what he could find.

Just a few minutes after takeoff, at approximately 9:35a.m. local time, Dwyer spotted the wreckage in a nearby cornfield. It was obvious the plane had hit the ground at a high rate of speed, as the main fuselage was a tangled ball of metal, wood and fabric resting against a barbed wire fence, while bits of debris and bodies were strewn across the field.

Eleven days earlier, the Winter Dance Party tour had kicked off on 23 January 1959 with a show in George Devine’s Ballroom in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Rock’n’roll tours were a genuine rarity in the Midwest, and the enthusiasm of the audience proved to be overwhelming. But Buddy Holly and the four other featured acts – Ritchie Valens, The Big Bopper, Dion and the Belmonts, and Frankie Sardo – knew they had a hard road stretching ahead of them.

Travelling through the flat, frozen plains of Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa during the harshest months of the winter would be a difficult task under any circumstances, but the booking agency, General Artists Corporation (GAC), had seemingly given little or no thought to geography while planning the tour. Rather than follow a logical path from city to nearby city, the tour instead would zig-zag its way between distant locations, guaranteeing gruelling all-night rides in bare-bones buses over icy and dangerous two-lane highways.

The Tour From Hell

Despite these challenges, Holly had little choice in signing on for the tour. In November 1958, he announced he was moving to New York and would no longer work with the Clovis, New Mexico-based producer Norman Petty. Holly and Petty had enjoyed a successful partnership for almost two years, scoring hit after hit. But as time progressed, Holly came to suspect that all was not well with his share of recording and songwriting royalties. The legal actions following the split led to Petty freezing all royalty payments to Holly. By January 1959, Holly was finding himself low on ready cash, and the offer to headline the Winter Dance Party tour offered the chance for some much-needed income.

Holly’s past experience on GAC package tours had been mostly pleasant, but times had changed for the rock’n’roll tour circuit. Rock’n’roll shows were simply not as profitable as they had been just a few years earlier. GAC badly needed to cut costs, and their performers’ comfort was where the axe fell.

The budget cuts were obvious to everyone who embarked on the tour. The performers were required to travel without a road crew, and were forced to load and unload their own equipment at each stop. Even worse, they were required to travel in cheap, second-hand school buses ill-equipped for the harsh road conditions and freezing temperatures, often traversing more than 300 miles of icy roads in a single night.

Within days the performers had worked their way through several replacement buses as they experienced breakdowns, severe lack of heat, and sleepless, all-night rides on the chilly and uncomfortable coaches. By the end of the first week, the performers were exhausted, and none had come at all prepared for the weather. Holly and Richardson were from Texas, and Valens was from Southern California, where freezing temperatures were a rarity. Even the New Yorkers, Dion and the Belmonts and Frankie Sardo, were underdressed for the sub-zero temperatures. The Winter Dance Party quickly received a new name, “the tour from hell”.

Fatal Flight

After reporting the location of the crash, Jerry Dwyer turned his plane back towards the Mason City Airport, landed, then hurried to his car to drive to the crash site. When he arrived, the police were already on the scene. It quickly became obvious that as the plane crashed, the right wing had struck the ground first, ripping it away. The remainder of the plane had cartwheeled across the field for 500 yards, crumpling the fuselage before coming to rest at a woven-wire fence.

Crash investigators later estimated the plane was travelling at 170mph when it struck the ground. The bodies of Holly, Valens, and Richardson had been flung clear of the plane as it tumbled across the field, with Holly’s and Valens’ bodies lying 20 feet south of the main wreckage and Richardson’s body 40 feet beyond the fence row. The body of pilot Roger Peterson was found crushed in the ball of the wreckage. All four men died on impact.

For Holly the turning point on the tour from hell came in the early morning hours of 1 February. On the evening of 31 January, the Winter Dance Party tour rocked the National Guard Armory in Duluth, Minnesota. Despite the hardships, the performers gave their all for each performance. Over 58 years later, one attendee, Bob Dylan – a high school student at the time – recalled Holly’s performance in his 2017 Nobel Prize lecture. “He looked me right straight dead in the eye, and he transmitted something,” Dylan said. “Something, I didn’t know what. And it gave me the chills.”

But a sparkling performance provided little comfort once Holly and the other musicians had traipsed back out to the freezing bus. They had been on the road for only a few hours when the vehicle slowed and came to a complete stop. With heavy snow falling and temperatures dipping to 35 degrees below zero, the musicians found themselves stranded on a lonely stretch of highway in the wilds of northern Wisconsin.

Cold Commute

While several of the musicians began burning newspapers in an effort to stay warm, Carl Bunch, Holly’s drummer, was having difficulty moving his legs and the pain in his feet was quickly becoming intense. In the dim light, guitarist Tommy Allsup examined Bunch’s feet, which had turned a disturbing shade of brown.

Finally, a deputy sheriff arrived on the scene and called for additional patrol cars that ferried the dangerously hypothermic musicians to Hurley, Wisconsin on the Wisconsin/Michigan border where they were able to get a few hours of warm sleep in a hotel. The situation was more dire for Carl Bunch. Diagnosed with a severe case of frostbite, he was admitted to the hospital in nearby Ironwood, Michigan, where he spent the next several days recovering.

A scheduled matinee show in Appleton, Wisconsin was cancelled, but the assembled musicians continued on to Green Bay, Wisconsin in the relative comfort of a Greyhound bus for an evening performance at the Riverside Ballroom.

The next day, 2 February, had been scheduled as an official day off, but a call from New York ruined any hope for rest and relaxation. Hoping to wring every possible nickel from the tour, a last minute booking had been arranged at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa – and it was 350 miles away. Holly and the rest had little choice, and boarded yet another second-hand school bus for the long trip west. “Surely,” Holly thought, “there has to be a better way to travel.”

As police and emergency calls about the crash filled the airwaves of Clear Lake and Mason City, a nearby radio station picked up on the reports while monitoring police calls. As soon as the first identification of the bodies was reported, the station began running announcements of the crash, as well as submitting the story to national wire services.

Terrible Truth

Initial announcements were short on details; many reported Buddy Holly’s death along with unidentified “members of his band”. At least part of this early confusion was caused by the discovery of Tommy Allsup’s wallet lying in the debris. The night before, Allsup had given Holly his wallet so he could use the identification to pick up a registered letter waiting for Allsup in Moorhead, Minnesota.

Surf Ballroom manager Carroll Anderson was called to make an identification of the bodies, and shortly afterwards corrected news reports went out over the wire services and the story was broadcast coast-to-cost over radio and television stations. No consideration was given to the families and friends of the victims. Maria Elena Holly would endure the shock of learning of her husband’s death through her television. Allsup spotted a picture of The Big Bopper on TV as he entered the Moorhead hotel; only when he spoke to the check-in desk did he realise the terrible truth.

By the time the bus arrived in Clear Lake, Iowa, Holly was fed up. They were exhausted and cold, and with no time to have laundry done the look and smell of his band’s clothing was becoming repulsive. As Waylon Jennings recalled in his 1996 autobiography, “We’d change in the dressing room, go on, get all sweated up, and then run back to the bus. We tried to hang our wrinkled suits in the aisle, and after a while, it got kind of ripe in there. We all smelled like goats.”

Last Call

On the way to Clear Lake, Holly suggested chartering a plane to fly himself, Allsup and Jennings to the next stop in Moorhead, Minnesota. It would give them time to get some sleep, take a bath, have their clothes laundered, and make arrangements for the following show. Allsup and Jennings agreed, and after arriving at Clear Lake, Holly asked Carroll Anderson to make the arrangements with the nearby airport in Mason City, Iowa.

During the show, JP Richardson heard about the plan. As The Big Bopper was over six feet tall and weighed more than 250lbs, attempting to sleep on the tiny bus seats was agony for him. Furthermore, he was coming down with a bad case of the flu. Desperate to avoid more bus travel, he had little problem convincing Jennings to give up his seat. Ritchie Valens, equally keen, tried the same tactic with Allsup. The two tossed a coin, with Valens winning the coveted spot.

Sometime during the evening, Holly made a call to Maria Elena. As she later recalled to writer John Goldrosen, “He told me what an awful tour it had been… everybody on the tour was really disgusted with the whole thing. He said the tour was behind schedule, and he had to go on ahead to the next stop to make arrangements for the show. He didn’t tell me that he was going to fly. I said, ‘Why should you go ahead?’ And he said, ‘There’s nobody else to do it.’”

End Of An Era

Holly, Richardson and Valens arrived at the Mason City airport at 12:40a.m. on 3 February. They were met by Jerry Dwyer, the owner of Dwyer’s Flying Service, and pilot Roger Peterson. The forecasts for the night indicated excellent visibility of 10 miles or greater. With the temperature dipping to 18 degrees Fahrenheit and wind gusts to 35mph with light snowfall predicted, conditions were less than perfect but still adequate for normal visual flight.

But Peterson had missed a weather advisory for lowered visibility due to fog and snow. This would necessitate flying by instruments – a skill he was not certified for. Also, the plane was equipped with an old-style attitude gyro which displayed the plane’s bank and pitch in the opposite manner to more modern instruments. For a younger, less experienced pilot flying with no visibility, it meant one might believe the plane was climbing when it was descending. Unaware of these potential pitfalls, Holly, Richardson, and Valens stowed their luggage and climbed into their seats – relieved for a respite from the tour from hell and oblivious to the destiny that awaited them.

Subscribe to Vintage Rock here