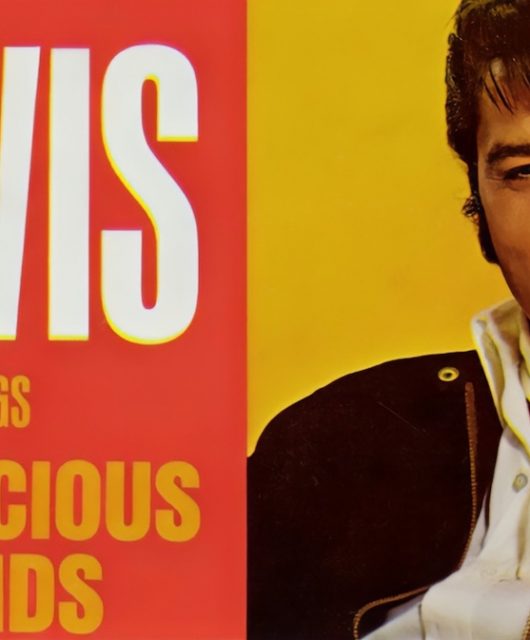

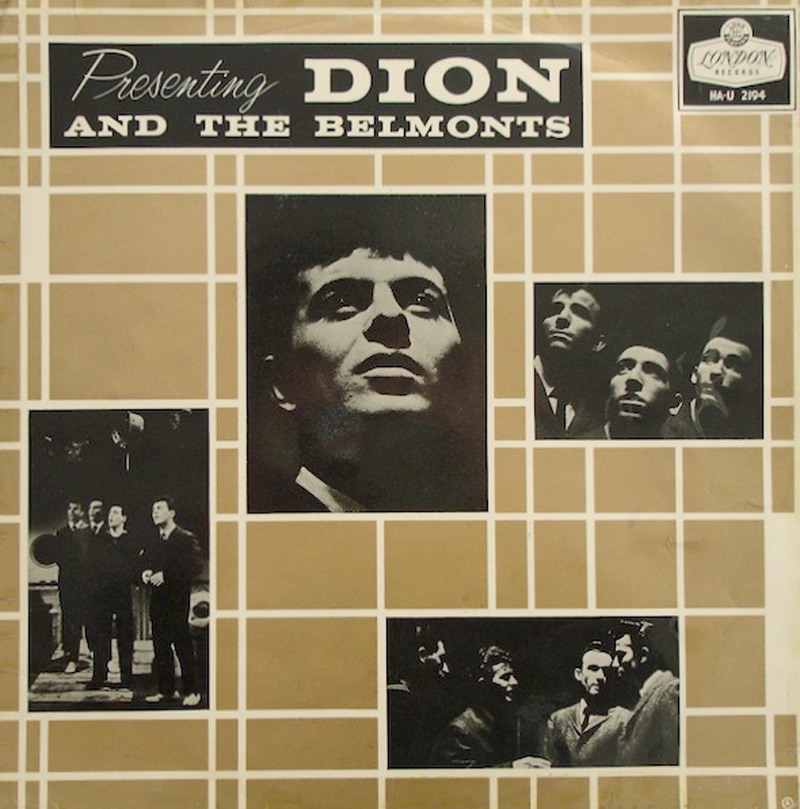

Classic Album: Dion And The Belmonts – Presenting Dion & The Belmonts

By Vintage Rock | July 16, 2020

Dion And The Belmonts’ debut album of 1959 stands proud as one of the rock’n’roll era’s great records and a high watermark of vocal harmony. We delve deep into its genealogy to find out why this particular Italian job remains something special…

When Presenting Dion & The Belmonts was released on Laurie Records at the tail end of 1959, doo-wop as a descriptive term for the type of music that these days we’d call the LP a classic example of, didn’t exist.

To most listeners the record showcased a quartet singing in a melodically harmonious, yet occasionally rough-edged style that they would have seen as a kind of off-shoot of rock’n’roll.

Dick Clark, in his sleeve notes, simply described these “four fellows” as a vocal group delivering “an interesting variety of songs.”

The term “doo-wop” first appeared in print in 1961 in The Chicago Defender and the phrase was attributed to radio disc jockey Gus Gossert. However, the desire among young record buyers for such sounds was already well-established.

“We were kind of exotic – which back then meant foreign – and that, in turn, meant dangerous”

Along with hits by other vocal groups, four of the songs on Presenting Dion & The Belmonts had already made the American singles chart.

I Wonder Why, the group’s first hit, had peaked at 22 on the Billboard Hot 100 in May 1958. No One Knows had bettered that, reaching 19 in the September of that year.

Then, after Don’t Pity Me had just managed to scrape into the Top 40 at the start of 1959, just as the buds had finished ripening and the flowers were starting to blossom, so in April 1959 did the group’s lovestruck youth anthem A Teenager In Love land them their biggest hit up to that point, springing to No.5.

Subsequent to that, another track on the album Where Or When would give the line-up the highest chart placing they would achieve together, making No.3 in January 1960.

Dion And The Doo-Wop Era

Dion & The Belmonts headed a white vocal group craze which brought hits for the likes of The Elegants (Little Star), The Mystics (Hushabye), The Bell Notes (I’ve Had It), The Crests (16 Candles), The Regents (Barbara-Ann), and the dreamily incomparable Skyliners (Since I Don’t Have You), whose lead vocalist, Jimmy Beaumont – surely the best of all the white doo-wop singers – died recently. Yet, notwithstanding the excellence of the hits these groups achieved, arguably none came to symbolise the sound of the era more than Dion And The Belmonts. I Wonder Why, which was backed by Teen Angel when released as a single, and A Teenager In Love in particular conveyed the energy and angst, tenderness and tears of late-50s adolescence, in a way that, with a touch more coy innocence, mirrored guitar-driven rock’n’roll.

The difference was that, instead of being good ole’ boys from the Southern states, the group was made up of four good-looking Italian-Americans hailing from the New York Bronx. While the few music history books that have troubled themselves to talk much about doo-wop have tended to frame the narrative around Dion, the Belmonts trio of Angelo D’Aleo (falsetto), Fred Milano (second tenor), and Carlo Mastrangelo (bass), had been harmonising together for years, having attended the same high school.

“We went through a host of names, most of them silly,” Angelo later recalled. “Fred and I were from Belmont Avenue and it seemed like a nice sounding name. It was that or we’d have been the La Fontaines or some other. Belmont had a nice ring so it so we kept that.”

While they had periodically encountered and sang with Dion DiMucci, who had also attended the same school, on their neighbourhood streets, they only properly came together after they’d both released unsuccessful singles for the same label, Mohawk. The Belmonts’ Teenage Clementine and Dion’s The Chosen Few had failed to make any waves, but Carlo had written a song called We Went Away that Dion had taken a shine to, telling Bob and Gene Schwartz at Mohawk that they should record it. Operating on the basis that, because the four lads knew each from their locality and clearly got on, the chemistry could work in the studio, Dion And The Belmonts were brought in to record the song together, but once again the single failed to sell.

Things were about to look up, however. The Schwartz brothers had plans to break away from Mohawk and form their own record label, called Laurie. When the quartet played them a new song they had come across called I Wonder Why, “they flipped,” recalled Carlo. “They told us they were getting out of Mohawk and starting a new label. We agreed to go with them and record it there.”

I Wonder Why has several elements of what would come to be called classic doo-wop. First off was the prominence of the bass voice. While this wasn’t unusual in vocal groups up to then, Carlo’s bass intro was strikingly prominent. Not only that, he was rattling off complete wordless nonsense. Just try writing it down. With the record played at normal speed you can’t, but “dnn nn nn, duh nn, dun nn dun nn nn nn nn nn nn naaaaa…” or whatever it was, it was a development from the sort of thing young neighbourhood vocal groups always loved to do, as a way of improvising for the lack of formal instruments, while they sang in streets, hallways or subways.

Another striking feature was the way the rest of the group, after Carlo’s into, brought up the melody, individually singing the words “know – why-I” and then, all together, “love-you-like-I-do”, before Dion’s gorgeous tenor took up the story. The beat was chunky, but the instrumentation light, barely noticeable, so that it retained a kind of heavenly a cappella feel, while retaining the edge of New York’s toughest streets.

The quartet certainly had an air about them. While Frankie Lymon And The Teenagers had given vocal harmony its major youth breakout song in 1956 with their hit Why Do Fools Fall In Love, the sound of a lot of the black vocal groups, in common with early R&B, had a certain maturity about it. Lyrically, too, their material tended to be adult, though those who lament the way white doo-wop supposedly watered down the earthier themes of black R&B are perhaps forgetting the highly romantic and sanctified songs the likes of The Harptones, The Orioles and The Penguins did so beautifully. The key element was the sincerity with which all the best of these groups, whether black or white, managed to present their material, which is why it still rings so true today.

Dion and The Belmonts were undoubtedly youthful and, with their Manhattan Lower East Side links, they had street cred. As Dion put it in his autobiography, The Wanderer: “There was something about the sight of four Italians, decked out in city slicker clothes, snapping their fingers, acting like Negroes. We were kind of exotic, which, back then, meant foreign, and that, in turn, meant dangerous.”

So convincing were they, with a lack of promotional material to precede them, many people who heard them on the radio believed they were black. They were one of the first white groups to perform at Harlem’s hallowed Apollo Theatre, but it was only because the boss had never seen pictures of them. In the event the show went so well, they were promptly re-booked.

The Ultimate Doo-Wop Album?

The songs on Presenting Dion And The Belmonts represent something of the personnel’s diverse musical interests, which spanned country and blues, vocal group harmonies, pop, jazz and even light opera. No One Knows, with its acoustic guitar, Dion’s close-mic vocal earnestness, and the muted “aaahs” from The Belmonts, could almost have started a new genre, that of the teen country weeper. The song was written by Ernie Maresca, who would be a key Dion collaborator after he went solo, writing songs such as Runaround Sue, The Wanderer and Lovers Who Wander.

Another song on the album written by Maresca was I Got The Blues. Technically, this was the “meaner” side of Dion, though if this was the blues, it was ersatz, delivered in a playful way. But Dion’s love of blues and country ran so deep it went to the heart of his style, and so songs like this presaged a lot of his later material. “I always said my early rock’n’roll was just black music filtered through an Italian neighbourhood, and it came out with an attitude,” he reflected in an interview in 2006. “I’d tune into radio stations from the South so I could hear people like Howlin’ Wolf and Jimmy Reed.”

Then there was his love of country music. Tommy Collins was one of the pioneers of Bakersfield sound, taken to its greatest commercial heights by Buck Owens, but Collins had a big hit on the country charts in 1954 with his self-penned song You Better Not Do That. Dion And The Belmonts’ revival on their album was inspired, ditching the fiddles while keeping the cornball humour, but adding saxes and handclaps over a jauntier rhythm. At this early stage in his career it was about as near to the stone country music Dion so loved as he could dare get away with.

Dion was, after all, a guy who had walked his local streets strumming a guitar and singing Hank Williams’ Cold Cold Heart. “A sound that might as well have been from the moon for all it had to do with the Italian Bronx,” he admitted.

In fact, though he’d later become reconciled to his Italian origins, in those early ears he felt restricted by them. It wasn’t just the poverty, but the music Italian-Americans listened to. “Everyone wanted to sing like Vic Damone,” Dion told Mark Rotella in his Amore: The Story Of The Italian American Song, “someone who sang as if all he did was take voice lessons.” Dion was doing a disservice to Damone, one of the greatest crooners, but it’s easy to see his point. While older Italian-Americans loved the smooth balladry of the likes of Damone, Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett, Dion craved energy and punch, and found his inspiration in the style of another of a more unorthodox Italian-American performer Louis Prima. “He was rock’n’roll man. Prima would have been the first guy included into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame if he didn’t sing in Italian.”

But as far as second tenor Fred Milano was concerned, The Belmonts’ inspirations were the great older vocal groups such as The Four Aces, The Four Coins and The Hilltoppers and even going back to The Mills Brothers. “We were making the transition from that sound to hearing the Alan Freed radio show out of Cleveland with groups like The Harptones, and Fred Parris & the Five Satins. All the groups, older and new, influenced us,” he said.

Just You showed the group in romantic mood, with beautiful harmonies and falsettos, and a sax and piano lending the most unemphatic backing. On this number Dion effected his emotionally troubled teen singing voice, which tended to have mixed results. It worked for Just You, but Don’t Pity Me and Wonderful Girl are love balladry at its feeblest. No wonder Don’t Pity Me barely scraped into the Top 40.

The group’s talents were shown to much better effect on two standards usually sung by older artists. That’s My Desire had been written back in 1931 and, ironically, another Italian-American Frankie Laine had enjoyed his breakthrough hit with his version of the song for the Mercury label in 1947.

Although generally perceived as a belter, Laine in those early days sang in a much more restrained, jazz-influenced style, and his brilliant performance of That’s My Desire was typical of this. Dion And The Belmonts, however, gave it a doo-wop makeover, with a brilliant falsetto counter melody.

On Where Or When, a Rodgers and Hart favourite, the harmonies were among the most beautiful the group ever achieved. It deserved its high chart placing, but A Teenager In Love, penned by a songwriting team more contemporary to the group, is the more remembered number in their catalogue. Doc Pomus and Mort Schuman would become known as two of the New York Brill Building’s finest songwriters, but A Teenager In Love was the first one they did together which became a hit.

Yet Pomus, speaking to Bruce Pollack for the latter’s book In Their Own Words, admitted he couldn’t even remember writing the song. “It was an assignment. We wrote the other side of that record too and I always liked it better.”

The song Pomus was referring to, I’ve Cried Before, also appears on the Laurie album. “We had a song that we’d already written called A Teenager In Love and Dion liked the lyric to it and wanted us to change the melody. So we just changed the melody.”

While you couldn’t say the song is quite up to the level of that other doo-wop teenage classic Why Do Fools Fall In Love it quickly became a standard. Rather unkindly, of the three versions of the song to make the British chart, the covers by the English singers Marty Wilde and Carl Douglas fared better than Dion And The Belmonts’ original, though all three made the charts at the same time. A familiar story…

But Dion And The Belmonts are now universally recognised regarded as the first white doo-wop outfit to hit the big time. At least no-one can take that away from them.

Jack Watkins