J.P. Richardson, alias the Big Bopper, shared equal billing with Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens on the tragic Winter Dance Party tour of 1959 on the back of his novelty masterpiece Chantilly Lace. Although destined to be a one-hit wonder, the track showcased a talented songwriter… By Jack Watkins

The Clear Lake, Iowa, tragedy of February 1959 is too often referenced for The Big Bopper to ever be forgotten. But of the three rockers who perished in the plane crash, next to Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens who in death achieved almost mythical status, his career details are little known.

The loss was great all the same. Although six years older than Holly and 11 years the senior of Valens, that still only made him 28. He left behind a wife, Adrianne Joy, and a four-year-old daughter Debra Joy, with the birth of his son (Jiles Perry Richardson Jr. who would later revive his father’s songs) coming just two months later.

And even if his back catalogue was the least extensive of the three, with just one substantial hit, Chantilly Lace, the artist was a much-loved individual with a career on the rise. Posters for the ill-fated Winter Dance Party tour gave him equal billing with Holly, Valens and Dion And The Belmonts. He was also a successful disc jockey and was showing great promise as a songwriter.

Born Jiles Perry Richardson in Sabine Pass, Texas, in 1930, and known as J.P., or Jape, his family had soon relocated to Beaumont, 40 miles to the north. As a Texas oil town, Beaumont’s large working population supported a lively entertainment scene. J.P. was raised on western swing and country, and his mother taught him to play piano. With a natural flamboyance, while still a teenager he’d done part-time deejaying on the local KTRM radio station, which was part-owned by one of his Beaumont High teachers.

By 1949, on leaving college, he was doing the job full-time, and his exuberant jive talk made him one of the most popular deejays in the region. Needing a catchy name, he first had the idea of calling himself the Big Yazoo, before settling on the Big Bopper. In 1957, he gained national attention by setting a record for non-stop deejaying when he spent five days, two hours and eight minutes on the air, playing a remarkable 1,823 songs in a sponsored disc-a-thon.

Yet Richardson had ambitions that extended beyond just spinning the platters. Even before a two-year period of conscription to the US Army in the mid-50s, he was writing songs. Bopper’s Boogie Woogie was a jokey spoken number he cut alongside a couple of other songs during a demo session in 1954 for Jay Miller’s Feature Records. Although unreleased at the time, the demos showed enough promise to hold out the possibility of a record contract with Excello had Uncle Sam not intervened.

Instead, it was Starday Records, during its short alliance with Mercury, who released the Big Bopper’s first single, under the name Jape Richardson And The Japetts in 1957. Crazy Blues, a slight rocker, was paired with the country waltz Beggar To A King on the flipside. The latter would be recorded by country royalty such as Hank Snow, who had a Top 5 country hit with it in 1961, as well as George Jones, Ernest Tubb and Rose Maddox.

But the single didn’t take off for Jape, who was a pleasant but uncompelling balladeer, tending to shine on the lighter material, which allowed his outsized persona to come through. Starday followed up by releasing his Monkey Song (You Made A Monkey Out Of Me). Somewhat ironically, on this rockin’ parody, Richardson seems to send up the hiccupping Buddy Holly style. A Teenage Moon (In A Rock & Roll World) was an amiable ditty, but once again the single made no impact on the record-buying public.

The next single, initially released on Starday’s subsidiary D label before it got picked up by Mercury, was released under the Big Bopper moniker. The intended top side was The Purple People Eater Meets The Witch Doctor, which utilised characters from recent hit novelty songs, David Seville’s Witch Doctor, and Sheb Wooley’s The Purple People Eater. However, it was Chantilly Lace, hastily written by Richardson on the way to the studio, which was favoured by radio jocks. With Mercury leasing the single and putting its greater promotional muscle behind it, it sprung up the national charts, reaching US No.6 in August 1958. In the UK, it would reach No.12 by the end of the year, the Big Bopper’s sole British chart entry.

Alongside the Bopper’s wolfish laugh, Chantilly Lace was bursting with great lines – the flirty “He-e-l-l-o-o B-a-a-a-b-y!” intro, the repeated declaration, “Oh baby, you kno-o-o-w what I like!”, and, of course, “a wiggle in the walk and a giggle in the talk”. No wonder teenagers lapped it up. A walking bassline and Link Davis’ riffing saxophone did no harm either. The Big Bopper knew how to put it across.

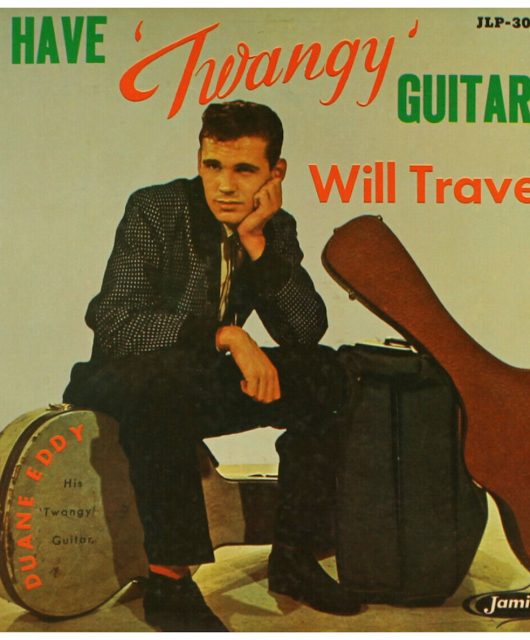

Cutting an imposing figure, he’d take to the boards in tiger skin-patterned coats, black slacks and white loafers, guitar hitched over his broad shoulders. You can see how likable and charismatic he was by watching a YouTube clip of him lip-synching Chantilly Lace on American Bandstand just months before his cruelly premature death. The song became so big, the Big Bopper was able to hand in his notice on the daytime job with the radio station.

But beyond being recalled whenever the fate of the Big Bopper is remembered, the song would also be granted a subsequent afterlife when Jerry Lee Lewis chose to sing it on his 1972 album The “Killer” Rocks On. Apparently suggesting on the spur of the moment during a session that he should cut the song, he ran though it in one spontaneous take and immediately declared it to be a hit. He was right. It spent three weeks at No.1 on Billboard’s country singles chart, and in Britain reached No.33 on the pop charts, his first entry since Good Golly Miss Molly in 1963.

During the summer of 1958, Mercury capitalised on the Big Bopper’s soaring popularity by slipping out a 12-track LP Chantilly Lace. It included a fabulous rocker White Lightning, which paid tribute to the potency of moonshine brewed up by the singer’s pappy “in North Carolina way back in the hills”. The song was destined to become a favourite among country-leaning rockers after the hard-drinking George Jones had a hit with it in 1959.

Naturally enough, the Big Bopper’s follow-up single was in the same novelty song vein. The double-sided Big Bopper’s Wedding and Little Red Riding Hood made No.38 and No.72 on the US national charts respectively before the end of 1958. Both songs did nothing to undermine the Bopper’s growing reputation for craziness, though they were probably a little too similar to his breakthrough hit.

Even so, it was all enough to ensure he was hot property when it came to selling the Winter Dance Party tour. The shows went well for him and Dion would later recall the fun of sitting in the back of the tour bus with him, Holly and Valens, while they shared each others’ songs. In the Iowa cornfield where it all ended on 3 February 1959, a briefcase found in the plane wreckage contained the lyrics for 20 new songs.

One of his compositions that had been put to use before his death was Bopper 486609 by Donna Dameron. Recorded in December 1958, the song was all set for release by Starday boss ‘Pappy’ Daily on his new Dart label in early 1959. Daily’s initial response in the light of events was to hold it back, before eventually deciding to release it that year. Written by the Bopper as an answer song to Chantilly Lace, poignantly, his voice, along with his laugh, is heard seconds from the end of the track (“Yeah honey, everything’s gonna be alright!”).

Had he lived, would the Big Bopper have risen beyond one-hit wonder status? Possibly not, but the penning of other popular classics like Running Bear and White Lightning to sit alongside Chantilly Lace, suggests he might have made a bigger splash as a songwriter.