In our lowdown on Fats Domino, we look at how his New Orleans sound was a cornerstone of early rock’n’roll…

John Peel liked to argue that rock’n’roll should feel scary and unhinged. You can see his point, but it’s only half the story. Bill Haley & His Comets, Chuck Berry and The Everly Brothers are examples of rock acts who thrilled and delighted rather than frightened or shocked audiences. Then there is Fats Domino, the placid, avuncular singing piano player from New Orleans. The keyboard rumbled and the backbeat was strong, but despite a phase when he took to using his ample girth to push the piano across the stage, he was never a raving rocker.

Contradictorily, while the peace-loving Domino was the least likely type to stir a fight, there were reportedly more riots at his shows than at those of any other US artist playing to teens in the 50s. The racial segregation rope that ran down the middle of the floor would literally be ripped up by the mixed crowds of dancers.

But a Domino concert was all about entertainment, the tunes delivered without menace.

The Rhythm King

If the point needs clarification, just compare his version of All By Myself with that of Johnny Burnette & The Rock’n’Roll Trio. Domino shuffles along in his endearing way, and there’s nothing threatening in his declaration, “Little girl, don’t you understand? I wanna be your lovin’ man!” and the suggestion to “Meet me in the park about half past one, we’re going out and have some fun.” Johnny Burnette, much more frantic, changes the lyrics, telling her to meet him behind the barn. He sings, “Don’t be afraid, I’ll do you no harm,” and it sounds like his idea of fun is going to be very different to Domino’s.

Burnette’s reworking certainly fits into the “unhinged rock’n’roll” gospel as preached by Peel, and maybe modern rock’n’roll fans will find it the sharper of the two records. Yet Rick Coleman called his biography Blue Monday: Fats Domino And The Lost Dawn of Rock’n’Roll (2006) for a reason. As Coleman sees it, before Bill Haley, Chuck Berry and Elvis, it was the man born Antoine Domino in New Orleans, Louisiana,in 1928 who first put the heavy African-American beat on the map.

He had already had a dozen Top 10 R&B hits in the period 1950 to 1955, before his first crossover smash Ain’t That A Shame arrived in 1955. The Fat Man, released in 1949, had reportedly sold over one million copies. Only Elvis shifted more records than Fats Domino from the 1950s up to 1963. Consistently underrated, Domino wasn’t a thrilling personality offstage, and his musical and performing style set itself in the 1950s and didn’t alter much for the rest of his career. But given the richness of the musical sources he’d drawn upon; he didn’t need to. And he did it all with a smile.

KEY SONGS

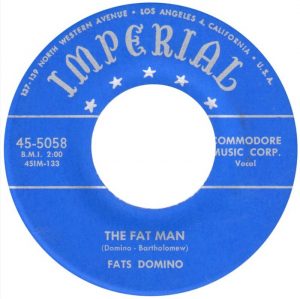

The Fat Man

Recorded in New Orleans at Fats’ first Imperial session in 1949. Issued as his first 45, paired with Detroit City Blues, it made No.6 on the US R&B charts. Despite its status as a pioneering rock’n’roll record, argued by some to be the first, the powerful backbeat created by Domino’s pounding left hand and Frank Field’s bass, was arrived at by accident. Producer Dave Bartholomew had unintentionally left the piano too high in the mix.

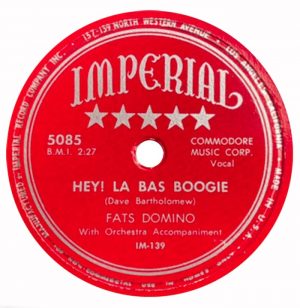

Hey! La Bas Boogie

Fine boogie-woogie and sparkling glissandos are fired across a racing R&B rhythm, on this reworking of a traditional French Creole song. Herb Hardesty offers some classic honking, and a battalion of saxophones come in at the end swinging like the Benny Goodman Orchestra back in the day, joined by Fats in a powerhouse finish. New Orleans rock’s melding of different musical styles was never plainer.

Ain’t That A Shame

Initially pressed as Ain’t It A Shame, this gave Domino his breakthrough on the newly created Billboard Top 100 in 1955, reaching No.10, as well as topping the R&B charts. The first Domino single on which the tape was slightly sped up to make him sound younger, it has familiar effects, including the country two-beat rhythm, his right-hand triplets, the signature electric guitar figure, and pauses and staccato sax for dramatic effect.

So Long

Rock’n’roll and gracefulness aren’t obvious partners, but how else to describe the swaying rhythms of New Orleans musicians? A souped-up blues ballad, this makes a simmering entrance via Fats’ piano, before being halted by thumping percussion. ‘Tenoo’ Coleman adds a steady beat and a brigade of sax players repeat a muscular horn riff. The lyric is forgettable, but Wendell Duconge’s alto sax solo is languidly elegant.

Blueberry Hill

Domino’s biggest seller has one of the most instantly recognisable intros of all time. A revival of an oldie, it was fellow New Orleans artist Louis Armstrong’s 1949 version that had convinced Domino it would suit his own mellow style. Remarkably, despite its simplicity, the 45 required multiple splices by Cosimo Matassa’s engineer, Bunny Robyn. Imperial boss Lew Chudd first refused to release it, eventually giving in to Domino.

I Can’t Go On

The flipside of Blueberry Hill when the latter was released in the UK, but itself a standalone classic. You can’t beat a speeded up country two-beat rhythm with added syncopation, as Chuck Berry showed with Maybellene. This was a horse from a similar stable, albeit the instrumental break supplied by sax not guitar. Berry’s song had a strong narrative, whereas Fats went for a soulful vibe, over and done in barely two minutes.

Blue Monday

Spare a thought for Smiley Lewis, another New Orleans R&B artist on the Imperial roster. Lewis sang the original Blue Monday, written by Dave Bartholomew, only to see Domino’s effort sweep past and make US R&B No.1 and No.5 on the Billboard Top 100. Many maintain the luckless Lewis’ grittier version is superior, but his mature sound was less appealing to teens. Domino performed this in the movie The Girl Can’t Help It.

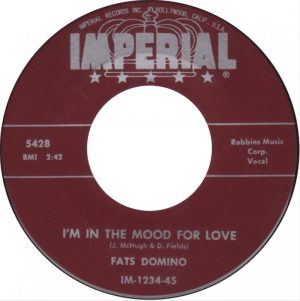

I’m In The Mood For Love

Cosimo Matassa marvelled at how Fats could make anything his own. The languorous delivery and French Creole pronunciation helped him charm his way through old chestnuts such as Dixieland standard Careless Love, a rocked-up My Blue Heaven and What Will I Tell My Heart?, all imbued with the New Orleans spirit. I’m In The Mood… had Fats at his most romantic, with a fine Bartholomew arrangement.

I’m Walkin’

Another of Domino’s biggies. Earl Palmer replaced drummer ‘Tenoo’ Coleman and added a rattling parade rhythm in the style of a New Orleans marching band, while Herb Hardesty blows a chirpy sax. Ricky Nelson recorded a cover at his first ever session and sold 60,000 in three days. Fortunately, Fats’ status as a credited co-writer ensured a decent payout and softened the blow. Palmer would later drum on many of Nelson’s sessions.

Be My Guest

Did Fats Domino make the first ska record? The off-beat rhythm on this song which made the Billboard Hot 100 Top 10 in 1959 has definite suggestions of the infectious Jamaican style that surfaced in the following decade. When Fats played some shows in Jamaica in 1961, he was hailed as a visiting monarch. Bob Marley is mentioned in Rick Coleman’s biography of Domino as saying that reggae originated with the man from New Orleans.

KEY ALBUMS

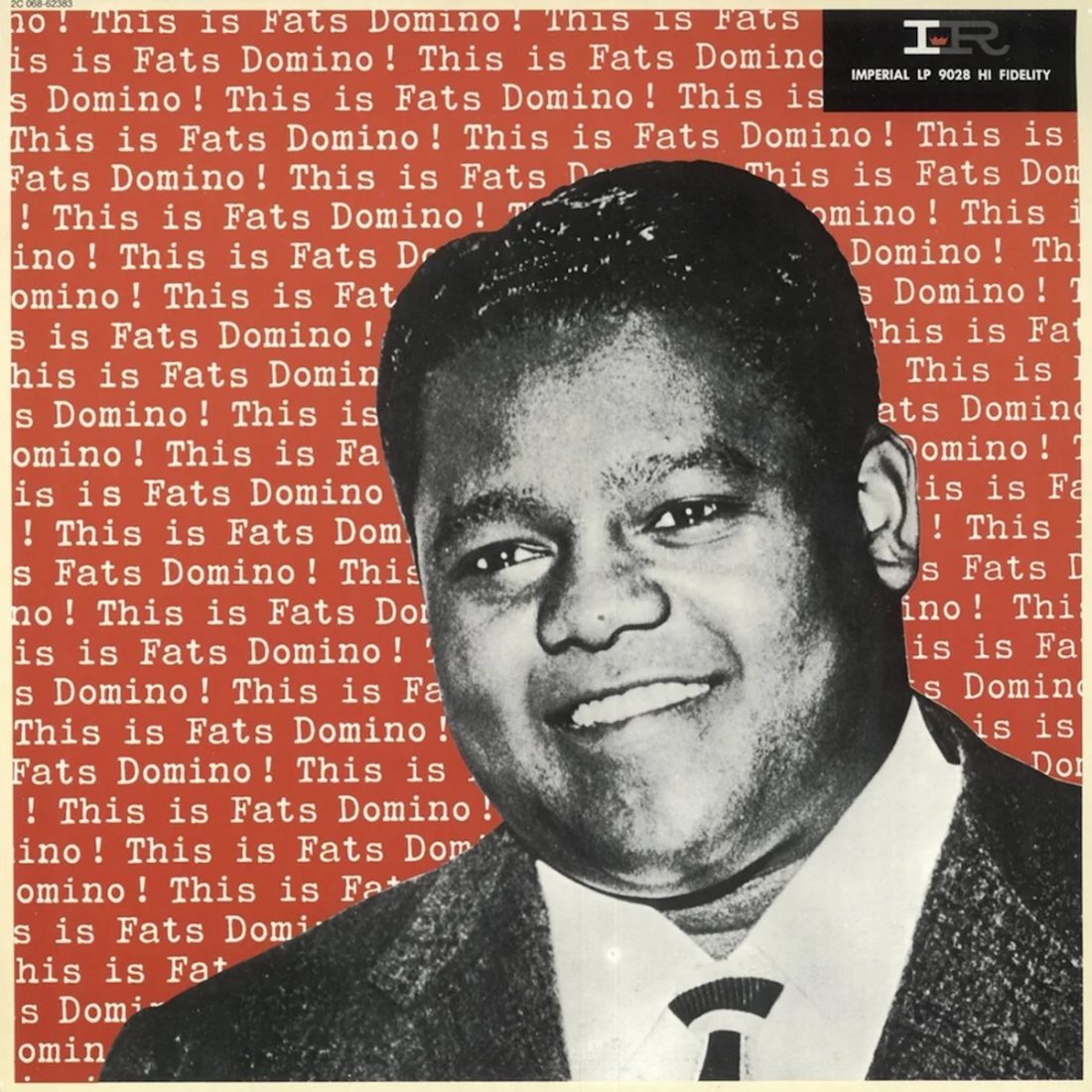

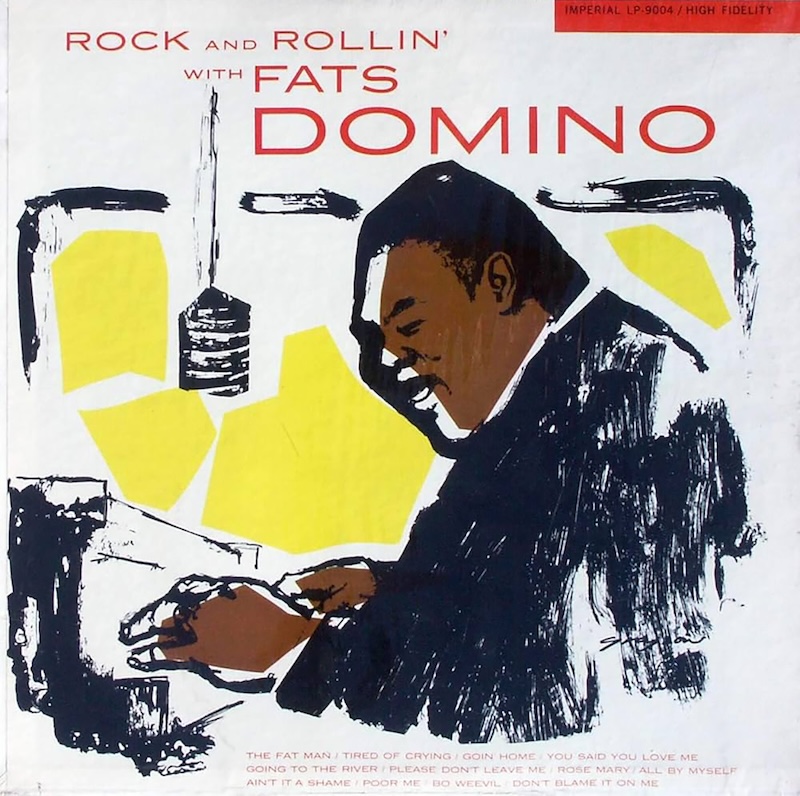

Several of Fats Domino’s Imperial albums charted, despite their reliance on familiar material. Graced by a striking cover akin to those given to top jazz artists of the era, his first Imperial album, released in early 1956, Rock And Rollin’ With Fats Domino made US No.17.

Follow-ups Fats Domino Rock And Rollin’ and This Is Fats Domino! also made the Top 20. In the mid-60s, though Domino was no longer a million seller or with the Imperial label, he remained good value as a live act, always working with an excellent band. Evidence is provided by Mercury’s Fats Domino ’65, a live recording of his Las Vegas show of that year, still backed by the cream of New Orleans R&B, including the saxophones of Lee Allen and Herb Hardesty, Roy Montrell on guitar, and Cornelius ‘Tenoo’ Coleman on drums.

Rock And Rollin’

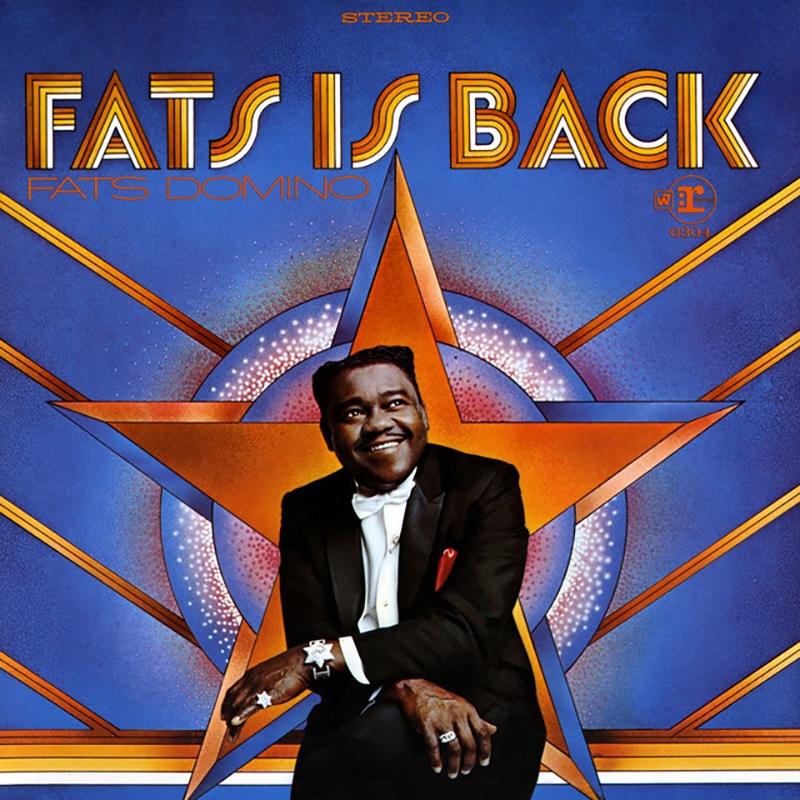

Fats Is Back, put out on Reprise in 1968, was an interesting attempt to give the Domino formula a gentle tweak. The Very Best Of Fats Domino – Play It Again, Fats was released in 1973 to coincide with Domino’s second UK tour, bottling the magic of the most charming rocker in the world in 16 of his classic Imperial sides.

For a cheaply priced CD round-up of Domino’s prime years, The Imperial Singles Collection (Not Now) is a good 75-track primer. Pricier, but with good notes, are Bear Family’s Fats Rocks (2007) and The Ballads Of Fats Domino (2018). But Bear’s magnum opus on the artist is I’ve Been Around: The Complete Imperial & ABC-Paramount Recordings, which extends beyond his great Imperial years to include his sides for ABC-Paramount between 1963 and 1965.

Thirteen of Domino’s Imperial recordings were speeded up when it came to release them as singles to make him sound younger, including Ain’t That A Shame, Blueberry Hill and I’m Walkin’. The Bear Family boxset also includes several of the songs in their authentic, as-recorded, speeds.

FATS ON FILM

In spite of being a poor movie, Shake, Rattle And Rock! (1956), featured a decent helping of Domino and his band performing I’m In Love Again, Ain’t That A Shame and Honey Chile. The Girl Can’t Help It (1956) pictured him in Technicolour glory singing Blue Monday, though the sax solo on the single version was omitted. His shy charm was in evidence in Jamboree (1957), performing Wait And See.

In The Big Beat (1958), as well as singing the title track, he could be seen jigging around and clapping his hands during the sax break on I’m Walkin’.

In 1973, he appeared in the rockumentary Let The Good Times Roll, singing My Blue Heaven and Blueberry Hill, the clips coming from one of his Las Vegas shows. Domino’s inherent country blues roots were underlined with his performance of Whiskey Heaven in the Clint Eastwood movie Any Which Way You Can (1980).

ESSENTIAL READING

A gap on the rock’n’roll biography bookshelf was filled in 2005 with the arrival of Rick Coleman’s Blue Monday: Fats Domino And The Lost Dawn Of Rock’n’Roll. The result of 20 years of research, it is incredible that the life story of such a major artist had been overlooked for so long. However, this also reflects Domino’s private, parochial nature and dislike of interviews.

The book reveals a character rather different to the persona projected on stage, but Domino took to Coleman and was generous with his time, regularly welcoming his fellow New Orleans resident into his home. Coleman argues that because Domino was such a loved and unthreatening figure, he was much more successful in internationalising the sound of the Big Beat than many of his showier, noisier contemporaries.

There are key insights into Fats’ working relationship with his more worldly, self-aware musical partner Dave Bartholomew, and the New Orleans backdrop out of which the music emerged. Coleman’s analysis of the Domino style and his dissection of his hit records is meticulous, in keeping with the approach to the entire book.

THE DOMINO SOUND

Primarily recording in New Orleans, Fats Domino’s studio output rested on trusted session players…

If Fats Domino represented the sound of New Orleans rock’n’roll at its finest and most commercial, he had help from some of Crescent City’s best talent. The backdrop was provided by Cosimo Matassa’s studios, initially situated on North Rampart Street and then, from 1956, on Governor Nicholls Street. Matassa operated as a guiding hand behind the control desk, giving insights when he felt they were needed, but seeing his main mission as to cut a sound as close to what he was hearing live in the room.

New Orleans bandleader Dave Bartholomew was Fats’ musical right-hand man, having introduced him to Imperial Records boss Lew Chudd, and became his co-writer and producer-arranger. The tux-wearing Bartholomew’s discipline was in contrast to the more laidback Domino, who had a habit of halting proceedings in the middle of a take to ask how he was sounding and turning up late or even missing sessions.

Crescent City’s Best

Domino brought his own box of tricks. He often sang “wah-wah” to mimic the harmonica, while his piano playing made big use of the powerful triplet sound that was to become a staple of the rock’n’roll era, acknowledging his debt to R&B star Amos Milburn, with Little Willie Littlefield, who played triplets on his 1949 hit It’s Midnight another possible influence. Domino’s phrasing, his soft, velvety tones and the Creole patois that made his revivals of old songs such as Blueberry Hill so effecting, was uniquely his, but the session players who were effectively Cosimo Matassa’s house band also made a huge contribution.

While credited with having helped develop rock’n’roll, their innate sense of swing meant they really carried on doing what came to them so naturally, perhaps with the volume dialled up a notch, and with a heavier beat. While Earl Palmer played on the first Imperial session in which Domino laid down The Fat Man, his long-serving drummer both in the studio and in his road band was Cornelius ‘Tenoo’ Coleman, often playing a shuffle while Fats’ piano drove the beat. Bass player Frank Fields who, like Earl, was a graduate of the Bartholomew band, as was guitarist Ernest McLean, who, with Walter ‘Papoose’ Nelson, played on many key sessions.

Above all, most of Domino’s songs featured a sax break, and chief among the players were Lee Allen and Herb Hardesty, as well as Wendell Duconge and Buddy Hagans.

Listen to Fats Domino here

Read More: Story Behind The Song – Fats Domino’s Ain’t That A Shame