The rock’n’roll world was overjoyed to hear news of Some Things Never Change, an album’s worth of mostly unreleased Carl Perkins material. Vintage Rock spoke to its producer Bill Lloyd in Nashville about its creation and subsequent disappearance.

Unearthing “lost” or unreleased tracks has become something of a fine art over recent years, with many record companies digging further into their archives to seek out rarities. Many of these finds might have been best left buried, and many rough takes, alternate cuts and bouts of studio banter only appeal to die-hard fans and musical academics.

It is therefore rare to find a full album of material that really should have seen the light of day a lot sooner – but this collection of 10 Carl Perkins’ tracks is of such high quality that its lack of a release after its recording in 1990 seems something of a mystery. While the tracks Baby, Bye Bye and Memphis In The Meantime did make an appearance on the Bear Family compilation CD Carl Rocks back in 2005, the remainder of the songs on the album have never been released before.

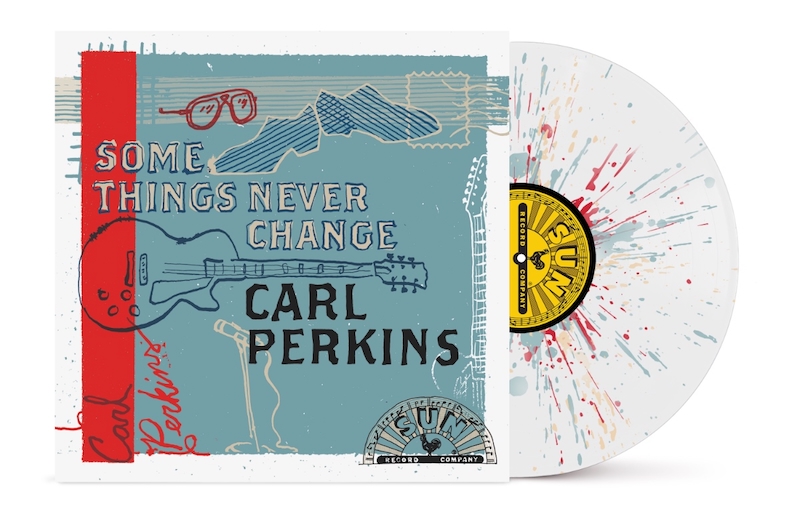

Now, Carl Perkins has “new” material, appearing on splatter vinyl and CD, on Sun Records once again. While Some Things Never Change is a worthy addition to Perkins’ discography, it does seem to have been an album that has been in some kind of limbo. “It looks kinda that way,” agrees Bill Lloyd, before documenting the creation of these tracks in more detail. “What happened was there were seven songs that were demos done at Carl’s home studio, which was in his pool house, right behind where he lived. He and his sons and I did seven or eight songs there and then I got a little budget to record some more in Nashville. So the first three songs on the album are songs that we had done in Nashville at a place called 16th Avenue Sound. It was a really great studio, Carl came up and we had a really great time.”

Newfound Treasure

The glaring question has to be what exactly was “the pool house” where these songs first came together? Was it a state-of-the-art studio adjoining the singer’s home in Jackson, Tennessee? “In my memory – half of the pool house was ‘stuff’, just like the most crowded garage you have ever seen,” laughs Bill.

“I remember he had a guitar out there that George Harrison had given him, made by some guitar-maker in Los Angeles, and he proudly showed that to me. I was like ‘Wow, this is beautiful’. The studio setup was, as you go in, off to the left and it was pretty cramped. It had a board with outboard effects and the recording was on tape, it wasn’t on digital.”

As one half of the successful country duo Foster & Lloyd, Bill’s relationship with Carl began on the road between 1989–1990. “We had opened maybe four or five shows for Carl (as a support) and that’s kinda how I got to know him,” he recalls. “As we had the duo-harmony sound, he would ask us to come sing on Your True Love in his set which was a lot of fun. Musically, the two bands were a good match.”

Radney Foster and Bill Lloyd racked up nine hit singles in the country charts during their initial time together between 1986–1990 and released a trio of albums during that period. With Carl enjoying songwriting success for his contribution to The Judds’ country smash Let Me Tell You About Love and George Strait covering his composition When You’re A Man On Your Own on the hit album Livin’ It Up, Perkins’ manager spotted an opportunity to have Lloyd help his client get some songs together that were geared towards country radio. “That was the idea,” confirms Bill. “Radney and I were on the radio at that time and our thing was a rockabilly roots kinda thing, slightly more rockier than most country stuff at that time. So we were a good fit, at least everybody thought so.”

Accommodating Fellow

The connection that Perkins and Lloyd had forged on the road seemed to be strong, so much so that during the pool house recordings Bill was invited into the rock’n’roll legend’s home.

“I met with Carl and his manager, I think it was one meeting, and he said ‘Well, come on down to Jackson and we’ll see how things go’. That was really a trial for me to how personally and musically that would fit. They treated me really well and we got on well enough to get the songs that we did and then when we got a little bit of money to do a few more in a good studio we came up to Nashville for that. It was two weekends when I worked with him in Jackson and he put me in the guest room.”

It must have been a strange experience to be living and working at Perkins’ home at that time?

“Carl made me feel totally at home. He’d knock on the door in the morning and say, ‘Valda’s got breakfast on.’ To me that was just so surreal, to be at Carl Perkins’ house. We really got to hang out, we got to enjoy being together, he was a very easy guy to work with. That was a surprise a little bit but he was a really sweet guy, a nice man. He would tell me stories and I remember being in his living room and over the fireplace was a paper bag that he had originally written the lyrics to Blue Suede Shoes on. It was framed above the mantelpiece and I remember just sitting there looking up at that while he was telling me all these stories about growing up and farming cotton – what a life he had.”

Nashville Sound

So it was that over two weekends in May and June 1990 that the initial recordings took place, in a setting where Carl was undoubtedly comfortable. Joining Perkins and Lloyd were Carl’s sons Greg and Stan, on bass and drums respectively, Joe Schenk on piano and pedal steel guitar player Pete Finney. The guest musicians were a combination of acquaintances of both Carl and Bill. “Joe Schenk was a guy who they worked with a lot. I’m not sure how local he was but he showed up in Jackson,” details Bill. “He came to Nashville and played too. Pete Finney was a guy I had been working with, he was in Foster & Lloyd’s live band, and since then he has gone on to play with everybody from Doug Sahm up to Reba McEntire, and he was with Michael Nesmith right up until he passed. On the Nashville session, Jerry Douglas came in and played the lap steel part on Memphis In The Meantime and it was cool to have him on there.”

Given Bill’s musical background, his position on the other side of the mixing desk was still a relatively new experience. “I had been an engineer on my own stuff, I did it when I had to do it, but I’m not technically an engineer, I’m more of a songwriter and musician,” he admits candidly.

So how were the recordings initially approached? Was it a type of live performance recording? “Some of it was. I remember there was a song called Miss Muddy which he just kinda launched into and I was like ‘Wait, wait’. They started playing this thing and it sounded like Carl was coming up with the lyrics kind of just off the top of his head but really the lyrics were too good for that,” says Bill with a smile.

“I think he really had that in his back pocket but he just hadn’t shown it to me yet. I ended up playing electric guitar on that. That was the one where I got everything set up and then I sat in. A lot of the time it was kind of methodical, like you would do in any studio, you get a drum and bass and maybe an acoustic or piano or something first. I got as much as I could that the equipment would allow in one sitting then did overdubs as time permitted.”

Classic Carl

Miss Muddy was not the only Perkins original that would appear on the album. Carl had been busy in the pool house studio prior to Bill’s arrival and there were a stack of songs for Lloyd to consider for inclusion. “The ballads, Where Does Love Go and Some Things Never Change, were two of the demos that Carl had that I just fell in love with,” enthuses Bill. “They weren’t up-tempo or rockabilly but they were just great songs and I really wanted to do those two.” Messin’ Around With Rock ’n’ Roll also caught his ear.

“I love that as a kind of personal history and it had this kind of Beatles-like lick and a whole lot of Buddy Holly-type key changes – it was a really cool arrangement. That was a favourite of mine. Out of his other own songs I also loved Baby, Bye Bye, I just thought that had all the earmarks of a classic Carl song to it and that’s one of my favourite tracks. We have both the demo version and the Nashville version on Some Things Never Change. When you hear that acoustic guitar that’s me and I get to sing harmony with him too. He did ask me several times, ‘Are you going to play on this’ or ‘Would you like to play on this?’ I played along on a few songs at Carl’s insistence, but I tried not to insert myself too much in the performance aspect.”

The boogie-fuelled Don’t’cha Know I Love You is the last of the original compositions, but out of the trio of cover versions which appear on the album, Bill found out that he unwittingly already had a connection to two of the choices, beginning with John Hiatt’s rowdy Memphis In The Meantime.

“John was my neighbour at the time,” says Bill. “But they had already talked about cutting that song. Heart Of My Heart was a cover that was pitched to Carl and his boys and they really liked it a lot. One of the writers of that was Bill Kenner who I had written songs with, but it wasn’t one of the ones that I had picked. I remember pitching them some other ones but Carl already had a big batch of demos that he had done and he still had the cassettes. We picked five or six. The version of Get Rhythm was also a surprise – it’s got this different groove to it. Greg and Stan started playing it and I said, ‘What’s that?’ and they said, ‘it’s the way we’ve been playing Get Rhythm.’ We messed around with it and that’s how that came about.”

Get Rhythm

After playing the demos to Mary Martin at RCA, a budget was secured and the artists all moved to the studios of 16th Avenue Sound in Nashville for a session between the 16–18 September, 1990. Bill Lloyd was still in the producer’s chair and making contributions on acoustic guitar, mandolin and harmony vocals. On this session there were added contributions from engineer Rick Will, who also mixed the tracks alongside Scott Baggett, and the aforementioned Jerry Douglas, something of a legend himself as a dobro and lap steel guitar player. It was a powerful creative line-up, but even at this stage the recordings still had no official destination.

“They were considered demos,” explains Bill, though “it was a step up from the pool house for sure,” he adds with a wide smile. “It was a big studio but it wasn’t enough to do a whole record, more of a case of ‘let’s just see what this is like.’ The first mix that we had, had a lot of that 1990s-era digital reverb kind of thing. The versions that appear on this record were done just a little bit later to take some of that ‘big drum sound of the 80s’ out. That was just done really when I had access to the tapes, and I thought if I’m gonna place this for anybody else I’d like it to be a little less

of that sound. So that’s why that was done, but still nothing ever really happened with any of this stuff.”

And here the mystery continues… Now that these songs are finally available in their entirety, they are of such fine quality that it seems strange that they never reached audiences of that time. Perkins was still in the wake of his 1989 album Born To Rock which, although cruelly labelled by some music biz cynics as an attempt to replicate Roy Orbison’s late career success, was a solid collection of mostly self‑penned material. His diagnosis of throat cancer was just around the corner, but thankfully he was to recover from that, and 1990s albums such as Friends, Family & Legends and the guest-star populated Go, Cat, Go were yet to come.

Memphis In The Meantime

What actually happened in the period after the recording of the songs that now appear on Some Things Never Change? “This is just sort of one that fell to the wayside,” says Bill with a shrug. “I made the mixes and gave them to Carl, his sons and their manager. The problem was that Carl’s manager at the time was managing The Judds, and Radney Foster and I (Foster & Lloyd) were also labelmates with The Judds on RCA Records. When The Judds were in the process of splitting up, and Wynonna went to MCA, I tend to think that’s why RCA didn’t follow up on this project. It just sort of sat there.”

Given the time that Bill Lloyd got to spend with Carl Perkins, did he ever pick up any hint that the artist was pondering over his place on the musical landscape of the time? “I think it was a reflective period for him,” Bill muses. “One of the songs we cut was Messin’ Around With Rock ‘n’ Roll and the lyrics are about ‘I didn’t know I was messing about with rock’n’roll/ I didn’t know “this” was going to happen/ I didn’t know “that” was gonna happen.’ It was very much him looking back at his career. So, yeah, I think he was reflective and frankly, Blue Suede Shoes was such a huge number and although he had cuts like Daddy Sang Bass for Johnny Cash and things like that y’know, that song hit hard and ever since then he’d been playing off of Blue Suede Shoes and then off of the cuts that The Beatles did, like Matchbox, Everybody’s Trying To Be My Baby and Honey Don’t. He also did that album with NRBQ in the early 70s.”

The passing of time seemed to have had little effect on Perkins’ songwriting abilities, and intriguingly there still seem to be more items in the archive that would surely get fans of the King of Rockabilly excited. “Yes, I have two 90-minute cassettes full of Carl’s demos,” reveals Bill. “It’s not the stuff I worked on but stuff they let me have so I could pick songs. I don’t know if they were all done at the pool house, they may have been done in Nashville or somewhere else. He wrote a lot; he was a really prolific songwriter. Everybody thinks rockabilly is just three chords and off you go, but he had great chordal changes and melodic changes and clever lyrics. He was a good songwriter. Dolly Parton came to write with him during the time that I was working with him. One of the times I went to work with him he said, ‘Hey, Dolly was here last week.’ He was excited about that; he thought that was wonderful.”

Worth The Wait

As these long-lost songs finally make it to a wider audience, it is worth reflecting how it was only through a casual conversation that this project came into being at all. “Sun Records got in touch with me, which was really nice,” explains Bill. “Ben Vaughn was a guy I had written songs with and he’s a songwriter and record producer from the Philadelphia/New Jersey area. He did a bunch of independent records over the years but he also had a career in Los Angeles as a producer and he also did music for TV shows and things like that. Ben was in touch with Laura Pochodylo at Sun and he mentioned ‘you should talk to Bill Lloyd, he’s right there in Nashville and he worked with Carl’. So it was really through Ben that she contacted me.” And where exactly were these lost gems located? “They were on DATs and there were some CDs that had been burnt over the years but they were largely unheard.”

It must be strangely surreal to find an old piece of work taking 35 years to reach an audience, but Bill seems enthused by the whole project.

“What’s so great about this package is that you get everything that was recorded – much of this has not been heard before, outside of the family really. It feels glorious, it’s something I’ve talked about over the years to my friends but now everyone can hear it. I would like to think that people who are tuned onto Carl, the Sun sound and roots music in general will find something to like here. I’m glad we are getting to hear it now. I love it, and it’s not just on regular black vinyl. That’s why I’m happy that it’s coming out and I’m also happy it is coming out on Sun Records.”

As new light is finally being shone on a little piece of Carl Perkins’ less well-known history, Bill Lloyd seems to be happy to have played his part in the proceedings. “I don’t mind telling the story, I think it’s fun,” he grins. “It just goes to show, sometimes good things happen to those who wait.”

For more on Some Things Never Change and to order click here

Read More: When rockabilly shook the world