Creator of some highly distinctive records, Jack Scott blazed across the stage with a voice that cemented his legacy as one of rock’s most electrifying pioneers… Here Vintage Rock evaluates his eponymous debut album…

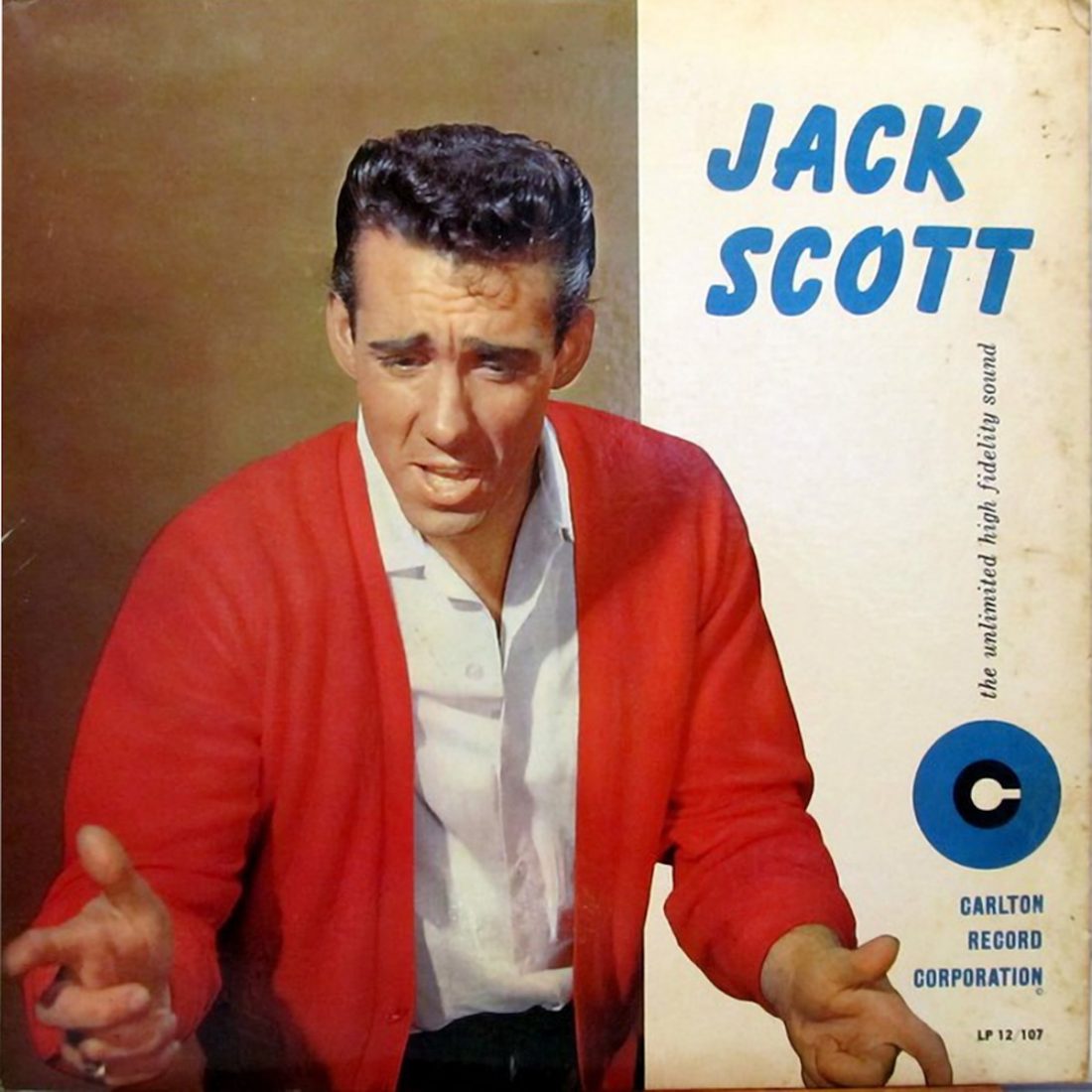

At 22, the lean, handsome, serious Jack Scott has embarked on a record career that will inevitably lead to the glamour worlds of television, cinema and theatre” predicted the sleeve of the singer’s eponymous debut album, released by the New York-based label Carlton in 1959. More accurately, it remarked that the record was “tremendous proof of talent that may never fully be tapped.” In an era when rock’n’roll LPs still played second fiddle to the singles market, Jack Scott certainly showcased a highly individualistic artist, his distinctive baritone unlike that of any other rock’n’roller on the scene at the time. Also, quite rarely, he was writing his own material.

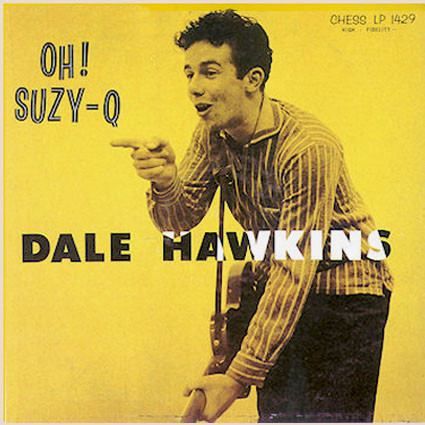

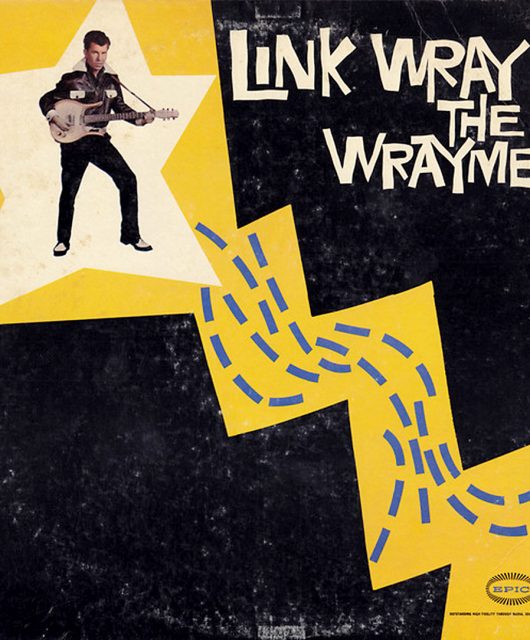

Yet Scott would never fulfil the golden promise of these early years. By 1983, Goldmine magazine was suggesting that he had been “both a mystery and a legend”; a legend because between 1958 and 1961 he had placed 19 recordings in the US Hot 100, and a mystery because after it he just seemed to fade away. How frustrating to fans has it been over the years to mention one of the outstanding tracks on Jack Scott, The Way I Walk to someone, only for them to immediately associate it with The Cramps’ likeably loony but inferior later version, or the one by Robert Gordon and Link Wray?

Walk This Way

But Scott achieved high status among British rock’n’roll fans, meaning he was still a revered name right up until his death was announced in December 2019. Though a somewhat reluctant traveller, his visits to these shores were treasured occasions. And any dedicated follower would surely agree that of the 12 songs on Jack Scott, nine of which were self-penned, eight of them are now regarded as defining classics of the man’s style.

The album blurb was certainly correct about one thing. He definitely was “a Canadian-born, Italian hillbilly who worshipped Hank Williams”. Scott confirmed the fact on a visit to the UK in 2015 to perform at the Camber Sands Rhythm Riot weekender and promote the album Way To Survive, his first in 50 years, while talking about his early love for country music and the development of his distinctive voice.

“I never met Hank but he was my idol back in the early days,” he told Vintage Rock, recalling that when he first started performing he tended to be a bit of a chameleon. “Back before I ever made my first recordings, if I was singing a Hank Williams song I sounded like him, and if I sang a Webb Pierce or a Carl Smith song, I sounded like them. But when I started writing my own songs, I couldn’t copy anybody. I sounded like me. If I sang Jailhouse Rock or Your Cheatin’ Heart I sang it the way I had heard it on a record. But when I wrote Greaseball (or Leroy as subsequently rewritten), I had to sing it as me. There was just no one else to copy.”

Rockabilly Rhythm

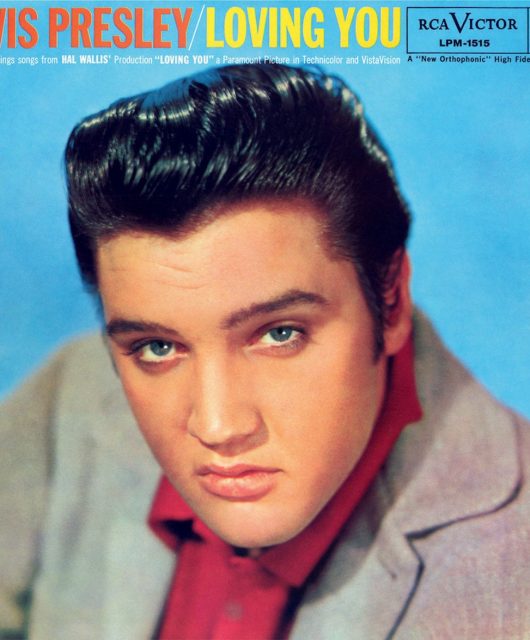

To be able to write his own songs was, therefore, the making of the man born Giovanni Scafone in the small Canadian town of Windsor, Ontario, in 1936, the son of two first-generation Italian-Americans, who moved the family to Detroit, Michigan, 10 years later. From his teens Scott performed at local schools, dances and on radio with his country band The Southern Drifters. But his first recordings, released in 1957 by ABC Paramount, reflect the impact the music of Elvis Presley had on him.

Baby She’s Gone had all the raw immediacy of the best of rockabilly, with feral interjections from Dave Rohillier’s lead guitar, while Scott strummed away on his flat top. Greaseball was recorded as a demo, with Scott delivering his snarling vocal over a driving beat. Its storyline was based around the nickname of one of Scott’s friends who been jailed. However, it was thought that the title might cause offence among the Hispanic community, and so it was changed to Leroy.

Backed by the first of what were to be Scott’s celebrated slowies, My True Love, it was put out by a small local label Brill Records, before being brought to the attention of Carlton Records in New York, under whom both sides became hits, Leroy making No.25 in the charts, and My True Love climbing to No.3. Jointly the two sides sold over a million copies.

Feral Flair

Jack Scott features both songs, as well as other Scott recordings for Carlton, made while he was still using the Universal Sound Studio in Detroit. They reflect the imaginative drive and songwriting flair of Scott at a stage in his career when he was thriving from being able to exercise creative control over his material. Without being taken in track order, the songs on it also reflect the upward curve of his career around this time.

A key to the development of the Scott sound was the association with a male vocal quartet, also from Windsor, Ontario, The Fabulous Chantones. For many people, this was to be the making of the Jack Scott sound, the combination of their voices with Scott’s baritone giving his ballads dark, soulful, almost doo-woppy textures. While they added extra propulsion to Greaseball/Leroy, it was on the slowie My True Love that their real value was revealed. “When it came to recording My True Love that’s when I decided I wanted to bring in backing vocals. I called up Jack Grenier, the leader of The Chantones and the first time we met at my mother’s house, we just blended. And it was the fashion at the time to have back-up voices,” recalled Scott.

They worked up the song from Scott singing the basic melody and strumming on his guitar, before Al Allen, who’d now replaced Dave Rohillier as lead guitarist, added an unobtrusive lick, with The Chantones instinctively falling in behind them. Despite the almost funereal pace, it was incredibly effective, even though Scott pushes his voice so deep at some points it seems to crack.

The same formula was used for With Your Love, which upped the emotional charge with Scott, mirrored by The Chantones , moving up an octave for the second verse, before then dropping back down again. It was actually a better song than its million-selling predecessor, but perhaps too similar for the buying public, because Scott had to be satisfied with just a No.29 chart placing this time.

Mesmerically Infectious

Although they went up-tempo on the next single, Geraldine fared even worse, only managing to reach No.96. Even so, it’s one of the Scott songs most often cited by fans, once again demonstrating his knack for the unusual. The lyric of this stop-time rocker essentially consists of Scott chanting the word “Geraldine” over and over again, only interrupted by occasional lines like “she’s cutest girl I’ve ever seen,” and the sax and guitar breaks. The result is mesmerically infectious.

Next up was another gem, Goodbye Baby, which, albeit at mid-tempo, also made effective use of the repetition formula on the words “Goo-oood-bye baby bye-bye,” with The Chantones used to achieve an echo effect on the last “bye”. Once again switching octaves between verses created a very soulful effect. A close-miked stand-up bass and acoustic guitar provided the spartan accompaniment. With its clever changes of emphasis and its abrupt end, this beautiful song was an imaginative reworking of the popular vocal group approach of the late 1950s. Written as a farewell letter to Scott’s girlfriend after he got his call-up papers, it deservedly climbed to No.8 in early 1959.

Save My Soul was on the flipside of Goodbye Baby and, sung in a rapid-paced gospel style, completely different from anything else on Jack Scott. The song was a result of the freedom Scott and The Chantones had in the studio at this time. “That song arose spontaneously,” Scott remembered in 2015. “We didn’t go in saying, ‘Oh, we must do a religious thing.’ Back then you’d go into the studio with the intent to do a couple of songs, and when we got there we’d often have time to try other things. There was no composer or arranger on those sessions. So that’s how a thing like Save Our Souls came about.”

Swaggering Strutter

Scott thought The Way I Walk which, despite only reaching No.35, has taken its place at the top of the list of his best-known songs, was only demo standard, until his label boss Jack Carlton flew in to Detroit from New York and, in a rare intervention, pronounced himself highly satisfied with the track. He may have been lovelorn on Goodbye Baby, but on The Way I Walk Scott sang like the swaggering, brawny guy who gazed out in his studio photographs, the muscular figure who liked nothing better than to lift weights in his free time. Reflecting the more extrovert lyric, there were electric guitar and sax solos, along with a supple boogie rhythm.

Scott’s confident vocal on the number was on a par with anything Elvis Presley, Gene Vincent or Eddie Cochran ever did. Mention should also be made of the contribution of the bass voice of The Chantones’ Roy Lesperance. Always notable, this was perhaps his outstanding moment on a Scott song, and in 2015 the singer spoke warmly of his partially-sighted friend contributing to a recent gig he had done, by now totally blind, yet still able to add his parts to the songs. “If I had to do it all over again and was offered The Jordanaires, I would still take The Chantones above them.”

Midgie was R&B delivered with a typically offbeat Scott flavour, but ironically, given his love of country and Hank Williams, the only ordinary track of the nine self-penned songs on Jack Scott was the country ballad I’m Dreaming Of You. His revivals of older country songs were also mediocre. The slow pace that worked on his own ballad compositions turned No One Will Ever Know, I Can’t Help It and Indiana Waltz into dreary dirges.

Goodbye Baby

Signing off from Carlton with a good, but not big-selling single There’ll Come A Time/Baby Marie, by the end of 1959, Scott was with a new company, Top Rank, recording in New York. The hits would continue for a time. What In The World’s Come Over You, again featuring The Chantones, was another strong, huge-selling ballad, reaching No.5. Burning Bridges, a stunning country weeper, soared to No.3. Other gems from around this time include Found A Woman, which was only a flipside, but had a typically whacky Scott vocal, and crazy couplets like “She’s not too keen, just a teen/ Sometimes works on a sewin’ machine.”

On Lonesome Mary, which stayed in the can for years, he regaled us with “Called a neighbour, where she’s at?/ Down the road with some dreadful cat.” There was more good work on this one from Lesperance. Then, after being transferred to the Capitol label, the rockin’ One Of These Days and lusher If Only were good songs in their differing styles. But the sales were slipping away.

“Music changed and I just couldn’t adjust to it,” Scott later recalled. He would make further good records as the 1960s progressed, getting to work in Nashville with one of his country heroes, Chet Atkins, in the producer’s chair, backed by the cream of Nashville session men. All I See Is Blue was a classy venture into Nashville Sound territory. Not until 1974, though, with You’re Just Gettin’ Better, again recorded Nashville, this time under the eye of maverick producer Gary Paxton, did he spend a few weeks in the lower reaches of the Billboard Country Chart. The consistency of imagination revealed on Jack Scott, though, would never be matched.

Listen to Jack Scott here

Read More: The Vintage Rock Top 101 Rockabilly Tracks