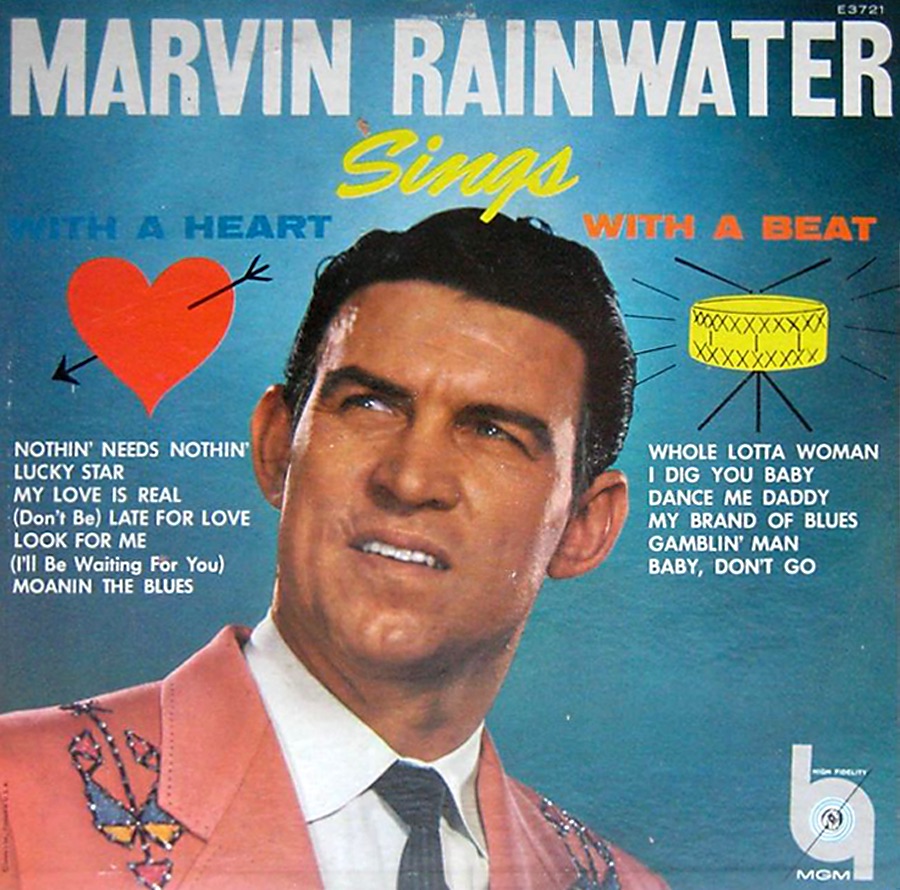

Classic Album: Marvin Rainwater – Sings With The Heart – With A Beat

By Jack Watkins | July 25, 2020

With his notable looks, baritone voice and Cherokee Indian heritage, Marvin Rainwater was an enigmatic star who stood out from the norm. One of the first American rock’n’roll stars to tour Britain, he topped the UK charts for three weeks in 1958 with Whole Lotta Woman. The track was taken from his Marvin Rainwater Sings With A Heart – With A Beat album, an LP of two halves that, as Vintage Rock reveals, is a reflection of a restless talent…

Through most of the 60s and 70s Marvin Rainwater’s career path had followed a faltering trajectory. The 50s hits had dried up, he’d had to back off singing for a while when calluses in the throat caused vocal problems, and even survived a cancer bout.

Through most of the 60s and 70s Marvin Rainwater’s career path had followed a faltering trajectory. The 50s hits had dried up, he’d had to back off singing for a while when calluses in the throat caused vocal problems, and even survived a cancer bout.

When he toured Britain, he played small clubs, his set framed round country material, performed in front of audiences who politely applauded when he stepped up a gear and broke into his biggest-selling UK single, the rocking Whole Lotta Woman. However, during a visit in 1979, he noticed a change in the audience profile and the way it responded to his material. Whole Lotta Woman still went down a treat, sure enough, but now younger fans seemed to be clamouring for what he considered old rockabilly obscurities he’d ditched long ago, songs like Hot And Cold and Mr Blues. The latter had been banned in some quarters on its release in 1956. Some folk had apparently thought he sang: “Why don’t you go f*** my baby” instead of the actual line which was “go bug my baby.”

To Rainwater’s amazement, these self-penned songs were now being recognised as elemental rockabilly classics, and it took him a moment to cotton on. “The kids were identifying with what I thought was great 25 years ago, so I thought well, I’m ahead of my time. Let me back my own mind up and go out and do what these people want me to do,” Rainwater recalled.

“Strapping guy that he was, Rainwater wasn’t exactly from the slim and youthful school of rockers”

From that moment this warm-hearted maverick, with his resonant baritone, ear for making songs with infectious rhythms, and irrepressible sense of humour, would find his niche in the rock’n’roll revival scene. Admitting the enthusiasm of the crowds made him “go into a trance”, he went on playing the festivals and weekenders almost right up until his death, aged 88, in 2013.

He was an enigma that divided opinion. Some listeners would get hung up on the fact that in his early days he went big on promoting himself as a full-blooded Cherokee, when really he was probably only about 25 percent native American.

Those who come at the music from the blues angle find his cornbread jokiness and curious intonation off-putting.

But if you love rockabilly best when it displays its barnyard roots, Rainwater has to be a favourite, even though he never really stuck strictly to any one style for long. That’s something that is reflected in the album Sings With A Heart – With A Beat.

The schizoid title was obviously supposed to reflect a first side of gentle ballads, and a second of more up-tempo material. But it also indicated a restless, versatile talent, writing most of his own material, and always experimenting.

Strapping guy that he was, Rainwater wasn’t exactly from the slim and youthful school of rockers who were emerging in the mid-50s, around the same time as him.

In fact, he was over a decade older than Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Gene Vincent. Born in Wichita, Kansas, in 1925, he admitted he was never sure if the surname was actually Indian, English or French. Despite his poor rural upbringing, it was classical music he initially concentrated on (“that’s why I was so mixed up” he later confessed, alluding to his unusual sound), before a garage accident which took off part of his thumb stopped him in his tracks. But it didn’t prevent him from teaching himself how to play the guitar.

“He could sound a little unsteady on ballads sometimes, but it adds to

the appeal.”

His vocal was initially inspired by the voice of Roy Acuff and singing cowboys like Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, as well as the classic honky tonk performers Hank Williams and Webb Pierce. All of these artists had an influence on Rainwater’s magpie vocal stylings.

In his early years he worked as a lumberjack, and he admitted to the British music writer Bill Millar that several times he put his life in jeopardy while musing over his song compositions during the process of felling a tree.

Early demo recordings reveal a nasal-toned country performer, his love of Hank Williams evident from the very first song, Hearts Hall Of Fame. Rainwater penned it on the day of Williams’ tragically premature death on 1 January 1953, going into the studio to record it the next day.

Not surprisingly, after I Gotta Go Get My Baby became the first Rainwater song to cause record companies to prick up their ears, the singer went with MGM, Williams’ old record company.

Over the next couple of years Rainwater would make some essential recordings, even if they didn’t make a great splash at the time. The unforgettable Tennessee Houn’ Dog Yodel and Get Off The Stool are classic examples of Rainwater’s hillbilly humour, while Dem Low Down Blues and Where Do We Go From Here? showcased his range and falsetto skills.

Around this time he was also bitten by the rockabilly bug, evidenced by the single Hot And Cold, backed by the stop-time rhythm of Mr Blues.

Unlike a lot of country artists who tried to get a cut of the new mania for rock’n’roll, Rainwater’s entry into the field sounded totally convincing. Like many other artists who had been listening to Bill Haley & His Comets, Hot And Cold’s sound was helped no end by the mean electric guitar of future country star Roy Clark, and Bill Badgett’s steel guitar.

“Bill had that fanatical, wild-steel sound. Off-the-wall stuff,” was how Rainwater put it. In this brief moment, Badgett made a steel guitar contribution to early rock’n’roll nearly as good as the work of Bill Williamson with Haley, and Speedy West with Tennessee Ernie Ford.

His pure country composition, Gonna Find Me A Bluebird, proved to be his major breakthrough. Rainwater’s beautiful lyric is underscored by the great Jimmy Day’s pedal steel guitar and an overdubbed “mockingbird whistle.” The result was his first million-selling hit, reaching No.3 on the country chart and crossing over into the pop Top 20.

The flip was a peach too – So You Think You’ve Got Troubles, or “so you thaa-y-y-y-nk you’ve got tr-uurr-bles,” as Rainwater sang it.

MGM chose to follow this success by changing tack, releasing the ballad My Love Is Real, before teaming Rainwater up with teenage vocalist Connie Francis on Majesty Of Love – the first Francis song to register in the charts.

It’s no surprise that Sings With A Heart – With A Beat offered such varied fare. The album followed a similar pattern to Rainwater’s first MGM long player, Songs By Marvin Rainwater, which was released the previous year.

There really isn’t a lot of difference in the standard of both records but, although the first album has the Rainwater classics Tennessee Houn’ Dog Yodel, Gonna Fly Me A Bluebird, Mr Blues and Get Off The Stool, the overall quality on Sings With A Heart –With A Beat is marginally more consistent. The sleeve notes called it a “neatly-balanced line-up of songs – six sentimental ballads ‘with a heart’ – six great novelties ‘with a beat’.”

Actually, that wasn’t strictly accurate given the first side contained Rainwater’s crackling up-tempo country composition (Don’t Be) Late For Love, with some fine work guitar work from Grady Martin. While Rainwater’s beefed up version of the Hank Williams classic Moanin’ The Blues, which closed the side, didn’t exactly slouch along either.

The fact that the slowies went on the first side probably reflected the confused priorities of the music industry in the late 50s, or maybe it was just the indifferent attitude of the MGM label, which largely focused on the pop mainstream. The singer’s approach to ballads was different to his other material – filing down the eccentricities and his nasal, almost adenoidal tone. He could sound a little unsteady on ballads sometimes, but it adds to the appeal.

A lot of his songs around this time were being cut in Owen Bradley’s recording studio, backed by Nashville’s “A-team” of crack session men. The curiosity of Rainwater’s unusual intonation added appeal to what might otherwise have been standard Nashville syrup. Nothin’ Needs Nothin’ (Like I Need You) was well-received and went to No.11 on the country chart.

My Love Is Real had a big vocal chorus behind it, but Lucky Star suited his voice better, having an almost Western feel.

Much stronger however was side two, kicking off with another Rainwater original, Whole Lotta Woman. This was another of his intermittent dabblings in rock’n’roll. “I mean that beep that I had on there was rockabilly,” he told Bill Millar for an interview later published in Millar’s Let The Good Times Rock! (published by Music Mentor Books). “I didn’t know it at the time, but that’s what it turned out to be. It was just something that was done inside of me and I thought it was gonna be a big hit.”

The performer’s hopes of another substantial Stateside hit were dashed, though. The references to “a whole lotta woman… gotta have a whole lotta man” were deemed offensive. Yet, the British, whose censors were usually just as thin-skinned, let the song through. It headed straight to the top of the pop charts, prompting Rainwater to tour the country in the spring of 1958.

On this tour, Rainwater was backed by Johnny Duncan’s band, which featured the great Denny Wright. Needing a quick follow-up single, while still in the UK, Rainwater went into the EMI studio in Abbey Road to cut I Dig You Baby, which was backed by Dance Me Daddy.

Both tracks were included on With A Heart – With A Beat and are early examples of an American rock artist recording with British musicians.

Backed by the Ken Jones Orchestra, these songs were unusual for Rainwater in that saxophones were more prominent in the mix than guitars, but they swung along in emphatic style.

Apparently Dance Me Daddy should have been “Rock Me Daddy” according to Rainwater, but for record company representatives fear of another suggestive lyric. The single, which reached the Top 20, represented the end of Rainwater’s short-lived involvement with the British charts.

The remaining tracks on the LP offer further evidence of his excellence. My Brand Of Blues, released on the flip side of My Love Is Real, was almost hauntingly brilliant, the singer sounding nearly as grave as Johnny Cash, with a subtle echo effect used on his vocal, over a train style, shuffle rhythm.

Recorded in New York, Gamblin’ Man was a reworking of the traditional song Rovin’ Gambler and reunited Rainwater with guitarist Roy Clark.

The album closer Baby Don’t Go, the B-side of Whole Lotta Woman, reflected Rainwater’s knack of creating songs with irresistibly syncopated rhythms.

“A cross between a genius and an idiot” was how Marvin Rainwater once described himself, admitting he’d been his own worst enemy when it came to his disjointed career. But behind the gawky backwoods persona, the gimmicky Indian costumes, and the happy-go-lucky jokes, was a serious talent.

At his best in the late 50s, Marvin Rainwater was about as good as anyone out there, and Sings With A Heart – With A Beat as the sleeve puff would go on to say, is still an album that “seems to get better each time one hears it!”

Jack Watkins