Bill Haley at 100 – A celebration of the Father Of Rock’n’Roll

By Jordan Bassett | September 24, 2025

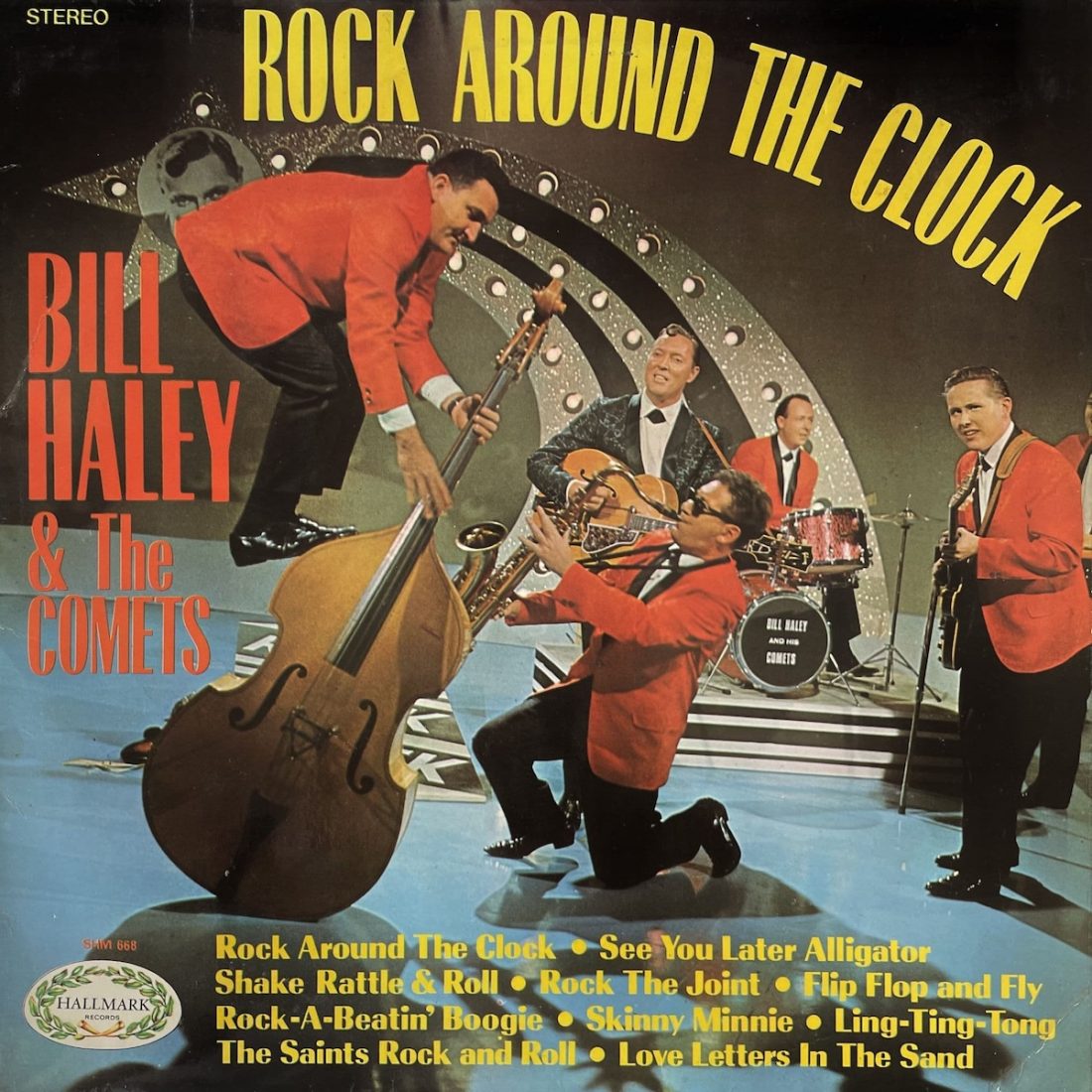

Along with his daughter Gina Haley and biographer Chris Gardner, Vintage Rock raises a glass to the Father of Rock’n’Roll, Bill Haley and His Comets, who changed the course of music forever with 1954’s incendiary single Rock Around the Clock.

Words by Jordan Bassett

As a youngster, Gina Haley knew very little about her father. Due to his traumatic death and the difficulty of his later years, her mother, Martha, seldom spoke about the figure who could, says his biographer Chris Gardner, be credited with having “invented rock’n’roll”. Gina was just five when Bill Haley died in 1981, leaving her with only hazy memories of a man whose legacy she’d grapple with for the rest of her life.

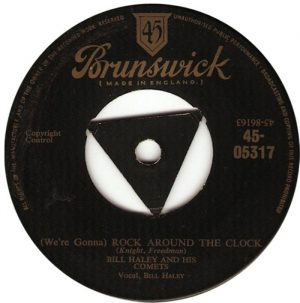

Certainly she didn’t grow up hearing his immortal 1954 hit (We’re Gonna) Rock Around The Clock, an incendiary clarion call that shifted more than 25 million copies, its staccato opening riff the sound of a youthquake in motion. During her adolescence, though, Gina’s burgeoning curiosity led to a startling revelation.

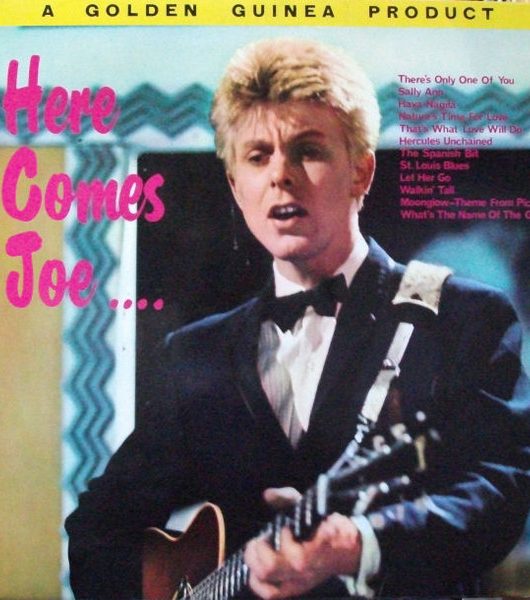

(We’re Gonna) Rock Around The Clock

“I discovered in a drawer that famous photograph of my father and Elvis,” she tells Vintage Rock, referring to the wonderful snap of rock royalty shaking hands in October 1955, Haley in a dickie bow and red blazer, the King looking louche in a black jacket and open-collared shirt. “My dad knew Elvis?” she marvelled.

“Can you imagine? Here’s my little brain: I’ve been sheltered; I don’t understand who my dad was. Any time I asked, nobody – my sisters and brothers – wanted to talk about him. It was all just hush, hush, hush. Random people would be like, ‘Isn’t your dad…?’ And I would be like: ‘Who is this Bill Haley?’”

It’s a question worth revisiting as we mark the star’s centenary on what would have been his 100th birthday, 6 July. A rock’n’roll pioneer, a father of 10 across three marriages and a born entertainer who played his first gig at 13, Haley massively influenced the course of popular music, laying the groundwork for Elvis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and every wild man and woman that Vintage Rock salutes to this day. Without Rock Around The Clock, much of the music we celebrate might never have been recorded.

The Journey Begins

William John Clifton Haley was born in Highland Park, Michigan, in 1925, his father a banjo and mandolin player, his British-born mother a classically trained pianist. When the Great Depression cratered their lives in Michigan, the family relocated to Bethel Township, Pennsylvania, where their young son fashioned a guitar out of cardboard and unwittingly began his journey into the heartlands of what would come to be known as rock’n’roll.

First, though, he would work as a record librarian at WPWA, a local radio station, absorbing the sounds of big bands, bebop and R&B as he programmed the likes of jump blues pioneer Louis Jordan (a name that will become significant in Haley’s story). From here, he formed Bill Haley & The Four Aces Of Western Swing, the band later renamed The Saddlemen – an outfit that specialised in covers of contemporary country songs. As Nick Tosches put it in his landmark 1984 book Unsung Heroes Of Rock’n’Roll: “All of Haley’s recordings through 1950 were common country records with their roots in slick Western swing.”

And then a strange thing happened. Once nicknamed ‘Silver Yodelling Bill’, Haley, who’d been left partially blind after a botched operation, adopted a ‘kiss curl’ hairdo (he apparently felt it distracted from his bad left eye) and swapped his western shirts for dinner jackets like the one he’d wear in that fabulous photo with Elvis.

In 1951, Bill Haley & The Saddlemen inked a deal with Philadelphia label Holiday and, instead of a recent country smash, recorded their version of Jackie Brenston And His Delta Cats’ Rocket 88, the super-charged fuzzbox single that had raced to No.1 on Billboard’s Rhythm and Blues chart. Like Rock Around The Clock, it’s been widely mooted as the first rock’roll song.

Rock The Joint

They soon covered Jimmy Preston’s Rock The Joint, the first instance, pop historian Bob Stanley has claimed, of an act combining both “country and R&B on a single”. The Saddlemen began to suspect that their countrified moniker didn’t quite fit the increasingly hard-edged music they were making, and so the punning Bill Haley & His Comets were born. (Initially, they were labelled Bill Haley With Haley’s Comets, which even the most forgiving fan would have to admit overexplains the joke a little.)

With his self-penned composition (an unusual prospect at the time), 1953’s Crazy Man, Crazy, Haley again bolted The Saddlemen’s country shuffle onto The Comets’ R&B groove. The result, a jazzy sound that bridged the big band style and rock’n’roll, would help to change his life. Esteemed session player Art Ryerson laid down the freewheeling guitar that sparkles against plodding bass laid down by long-time Comet Marshall Lytle, who co-wrote the song with Haley, and the single shimmied to No.12 on the pop chart, making it the first rock’n’roll hit from a white act.

By fusing R&B and country, The Comets set the template for Elvis’ groundbreaking debut single That’s All Right and Chuck Berry’s’ Maybellene, which arrived in 1954 and 1955 respectively. “You listen to Crazy Man, Crazy ,” Haley’s biographer Chris Gardner tells Vintage Rock, “[and realise that] he was so ahead of the curve for a while.”

Ahead Of The Curve

In terms of chart success, though, the world had seen nothing yet when it came to Haley’s potential. Given the performance of Crazy Man, Crazy, it was only natural that he’d leap from Holiday to the more prestigious Decca Records in 1954, the year that the Comets first nudged the dial of popular culture with Rock Around The Clock.

This is where Haley reencountered a certain jump blues pioneer, as Decca recording director Milt Gabler testified in John Chilton’s 1992 book Let The Good Times Roll: The Story Of Louis Jordan And His Music: “I never played Louis Jordan material to Bill Haley. There was no question of close copying, but I used to sing the group riffs from Louis’ records. Also I got the tenor sax player and the pianist to think along those lines, and I asked the whole group to project the way that Jordan’s group had done.” With that in mind, the Comets’ stiffened delivery and precise arrangements clearly echo Jordan And His Tympany Five.

The subsequent Rock Around The Clock was written by Max Freedman and Jimmy De Knight, a couple of Tin Pan Alley stalwarts (the latter had worked with The Comets’ frontman since the 1940s). Haley whoops it up from the song’s opening moments, responding to the fanfare of Billy Gussak’s declarative rat-a-tat drums with his ironically timeless mission statement: “One, two, three o’clock, four o’clock – rock!”

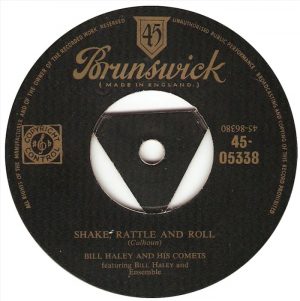

Shake, Rattle And Roll

His vocal is bright, clean and upbeat, exuding none of the racial ambiguity that would define That’s All Right or the raucousness that burst from Little Richard’s earth-shattering breakthrough single Tutti Frutti. The band, though, is red-hot, bouncing through the track with a swagger that’s pure rockabilly and a lightness of touch that would come to define pop music much later in the century. Gardner still spins the tune almost every day.

“The energy in that recording is just something else,” he enthuses. “There’s a magic in that.” During their prime, says Gardner, The Comets were untouchable: “When you listen to Rock The Joint, you think, ‘Wow, that’s different!’ And then: Rock Around The Clock. My God! Where did that come from? He had great musicians. He had the hillbilly musicians from his past, but when they get in a drummer like Billy Gussack and a guitar player like Artie Ryerson, suddenly you’ve got top-flight musicians.”

Case in point: the band’s 1954 cover of Big Joe Turner’s Shake, Rattle & Roll, a slap-bass sizzler that steamed up the Top 10 on Billboard’s pop chart, finally resting at No.7. “There’s a couple of years in there,” continues Gardner, “from ’53, ’54 and a bit going into ’55, where the chemistry was absolutely spot on.”

Time To Rock

Tucked away as the B-side to the chirpy Thirteen Women (And Only One Man In Town), the song made little impression on the record-buying public. But Rock Around The Clock’s time would come. This was thanks to Blackboard Jungle, the 1955 smash adapted from Evan Hunter’s novel of the same name. Directed by Richard Brooks, the movie centres on Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford), a rookie teacher who takes up a post in what looks suspiciously like a Brooklyn high school.

Here, he encounters a gang of hoodlums led by Gregory Miller (Sidney Poitier in his breakout role), a gifted musician who could enjoy a bright future if only he’d lay off the juvenile delinquency. The movie was intended as a moral panic about teenagers acting out against their elders – and even opens with a po-faced public service announcement to this effect – but inevitably appealed to viewers who fit that very description.

If the film’s action moves a little slowly by today’s standards and some of the dialogue is more than a little hammy, Blackboard Jungle somehow still remains shocking. When Miller arrives at the school and moves through a shoal of grease-haired teens, it’s shot like a horror movie; the kids really do ooze menace. While young audiences were no doubt wooed by these characters’ dark glamour (though hopefully not the violence that they commit), the movie’s soundtrack certainly helped.

Blackboard Jungle

When Rock Around The Clock blares over the opening credits, Hunter’s tale bursts into life. The track summons the spirit of the era, shifting the emphasis from criminality to the emergence of a generation with its own rockin’ values – and to hell with their parents’ stuffiness. Given that said generation was blinking out from the shadow of WWII, it’s little surprise that the film so resonated (reports of riots in cinemas did play into the filmmakers’ hands, however).

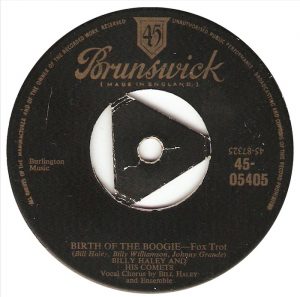

Even less surprising is that Rock Around The Clock was re-released as an A-side single after the success of Blackboard Jungle. By now, The Comets had scored further Top 20 pop hits with Dim, Dim The Lights (I Want Some Atmosphere) and the typically jaunty Birth Of The Boogie. The re-release spent eight weeks at the top of the Billboard pop parade, becoming the first rock’roll track to reach No.1 on the chart. Two decades later, the song re-entered the zeitgeist (and the Billboard chart) when it appeared in the 1973 George Lucas movie American Graffiti and featured as the theme tune to the smash hit sitcom Happy Days for two seasons.

Birth Of The Boogie

Haley was almost 30 years old when the song originally found success. Suddenly he had arrived as a major star, rubbing shoulders with Elvis Presley (who reportedly named Rock Around The Clock his favourite song). Alas, Haley would soon become a victim of his own success, superseded by the looser rock’n’rollers who entered in his slipstream and, ultimately, siphoned off his record sales, which swiftly began to dwindle.

It’s here that Chris Gardner makes his bold – albeit heavily caveated – claim about Haley’s legacy: “If you like, he invented rock’n’roll. He didn’t, but it’s a useful phrase to use because he was the first person to have a hit rock’n’roll record.” Bill, though, was a quiet man ill-suited to the chaos of the oncoming rock’n’roll era, which was led by stars around a decade his junior: “Elvis, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis, they were much more outgoing people. Bill was actually, in my analysis, the end of the big band era rather than the start of rock’n’roll.”

Gardner adds sadly: “He couldn’t adapt to new trends and wasn’t terribly innovative. Elvis developed; you always felt he knew what he was doing and he always managed to sell records, right through his life. But [Haley] just got left behind because he couldn’t change.”

New Shores

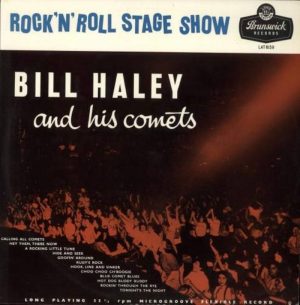

Haley parted ways with Decca in 1960, jumping ship to Warner Bros. After Rockin’ The Oldies, his covers collection of standards from the preceding decades, somehow didn’t turn the kids’ heads, he bounced between labels for the rest of his music career. The erstwhile ‘yodelling Bill’ did attempt to explore new ideas in the wake of his mid-50s pomp, releasing Rock ’n’ Roll Stage Show, mostly comprised of originals, in 1956. “That was rather interesting,” comments Gardner, “because that was, if you like, the world’s first concept album – an album of a stage show that Haley might have done somewhere.”

Bill Haley & His Comets also cut an effective instrumental album, 1959’s imaginatively titled Strictly Instrumental, and scored some commercial success in Mexico (that became his adopted home for tax reasons in 1960) with a series of twist records. Unfortunately, this did little for his popularity in the States and, therefore, the rest of the world.

Rock ’n’ Roll Stage Show

After the twist records in the early 60s, his discography begins to slow down quite dramatically, with Haley’s output over the next decade-and-a-half dominated by covers of classics and re-recordings of his own tunes. Another outlier, 1971’s Nashville hoedown album Rock Around The Country, features a track called Dance Around The Clock. The album’s not bad. Like much of his music post-1955, though, it was simply out of step with the tastes of the American public, which he couldn’t seem to latch back onto.

Given the enormous debt owed to Bill Haley for Rock Around The Clock, however, he’s nowhere near as well-remembered as he should be. Gina Haley is currently studying and teaching Music Pedagogy and argues that the education system should put more emphasis on his achievements.

“I cringe,” she says, “because they mentioned my dad in, like, one little paragraph. I’m like, ‘Why?’ I mean, I get it. Right now, the credit is certainly due to all of the African-American musicians that brought this music to us. For that, I get it. But I also wish that there was more knowledge about how his jazz influences came together with rhythm and blues and country and western. I don’t think there’s a full understanding of that.”

Still Rockin’

Gina hopes that a new book, Bill Haley: Rockin’ Around The World At 100, will correct this. The tome is based on an unfinished autobiography that Haley was working on before his death. It “peters out,” says Gardner, “in the late 50s,” but he and fellow author David Lee Joyner have managed to piece together the rest of the narrative. Gina’s brother, Pedro, provided an emotive foreword. At the time of writing, the book is tentatively due for release in July 2025.

In addition to stumbling upon the snap of her dad and Elvis, adolescent Gina also discovered the autobiography manuscript as well as audio recordings: “When I heard his voice, that’s when there was this tremendous, really, really forceful drive in me to want to get to know my father.”

When Bill Haley’s discography slowed down in the 1960s, his drinking increased and his mental health imploded, his behaviour eventually so erratic that wife Martha ejected him from their Texas home. He moved into the pool house, the windows of which he reportedly painted black during one manic episode. Haley was just 55 years old when he died, after years of alcoholism, from a suspected heart attack (there were also rumours of a brain tumour). The end was so traumatic that the family erected a wall of silence around his name.

I’ve Got A Feelin’

This made his legacy doubly complex for Gina, who didn’t want her work to be defined by her father’s: “I was already singing, performing and writing my own music, so there became this struggle that I would feel for most of my life, where I’m conflicted. I was old enough to understand that historically my father played a really huge role in American music and it wasn’t matching [his place in history]. He was being forgotten. But as I would soon learn, it’s very complicated, when you’re the child of a celebrity, to have your own career. It’s almost unfair.”

Once into her twenties, Gina immersed herself in the Los Angeles music scene. “But all the while,” she says, “in the back of my mind I have this weight, this pressing feeling that I need to be doing something for my dad. That was difficult because it was a constant nagging.”

When surviving members of the golden era Comets (whose line-up shifted dramatically over the years) Franny Beecher, Dick Richards Johnny Grande, Marshall Lytle and Joey Ambrosio were inducted into Guitar Center’s Rockwalk Hall Of Fame in Hollywood in 2005, Gina attended the ceremony and ended up performing with the band. “It changed my life,” she says. “I needed to meet those guys. They embraced me. They were so lovely and I felt like, for the first time, I was close to my dad. It was so weird: when I hugged them, I felt like I was hugging my father.”

Author Otto Fuchs then invited Gina to perform her father’s songs throughout Europe in celebration of his 2016 book The Father Of Rock & Roll: The Rise Of Bill Haley. She agreed, telling herself it was a one-time-only deal. “I had to make that decision: if I go and sing my father’s songs, there is a risk that that could be all I’m known for. But this opportunity had presented itself to let the world know that he’s got family who are still trying to do something to keep his memory alive.”

The retro concerts were so successful that Gina recently teamed up with modern swing band The Jive Aces for her first album of mid-century R&B material. I’ve Got A Feelin’, released earlier this year, boasts piping hot covers of Ann Cole (I’ve Got A Little Boy) and Ruth Brown (Wild Wild Young Men), as well as Shake, Rattle & Roll.

Swing When You’re Winning

In the late 2010s, Gina Haley was “poking around” on Facebook and stumbled upon a band she liked the sound of: “I was like, ‘Oh, those guys look fun – I wanna work with them!’” That band was The Jive Aces, the British modern swing group who shot to fame after appearing on Britain’s Got Talent in 2012.

She messaged the Aces, suggesting that if they were ever in her neck of the woods, they should give her a shout. “To my great surprise,” she says, “one day I get a message from them: ‘Hey, don’t you live in Texas, near Dallas?’” The band were due to play in McKinney, a nearby city, and invited her to perform with them that very evening. There was no time for rehearsals, but the show was a barnstormer, with the group and their new singer tearing through golden age R&B tracks that they shared a love of.

“We became fast friends,” Gina beams. At one point, the band suggested they make a record and suggested she find a studio. By chance, one week later, she received an email inviting her to make a record at Sugar Ray’s Vintage Recording Studio in Wickford, UK. Stacked with original 50s equipment, it was the perfect place for Gina and the band to cut I’ve Got A Feelin’, their new jaunt through the classic R&B songbook.

“When I’m with them,” she says, “I just want to do better. They have this energy about them that rubs off on you.”

When she chats to Vintage Rock, Gina and the Jive Aces had showcased the new record at London’s 100 Club.

To mark her father’s centenary, the show featured a selection of his songs. These days, though, she struggles to choose just a few. “It’s so funny,” Gina says, “because I was looking at the setlist and I was like, ‘I said I wasn’t gonna do any more Bill Haley songs, but I wanna do all of these!’ That’s how much I love the songs now. I’m like, ‘But I love this one – and this one! And this one is so good…’”

Order Bill Haley At 100: Rockin’ Around The World here For more on Gina Haley & The Jive Aces! I’ve Got A Feelin’ click here

Subscribe to Vintage Rock here