When Rock’n’Roll Goes Gospel… Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard and Johnny Cash all released gospel records at the height of their fame and fortune. Now largely forgotten or underrated, the albums are ripe for reassessment. Words by Jordan Bassett

It’s one of the most famous scenes in rock’n’roll. Louisiana firebrand Jerry Lee Lewis is rockin’ up a storm at Sun Studio in Memphis during the recording of Great Balls Of Fire, the classic single that will become his signature tune. Between the takes, the god-fearing Jerry Lee frets that the raunchy song is “sinful”, which leads Sun Records boss Sam Phillips to assure him that his music could “save souls”. Jerry Lee is distraught and cries out: “No, no, no, no! How can the Devil save souls? What are you talkin’ about? I got the Devil in me!”

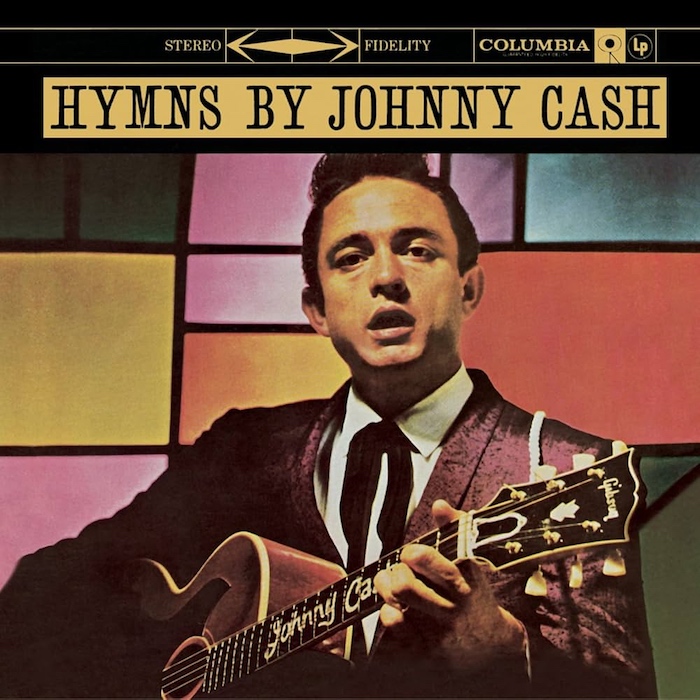

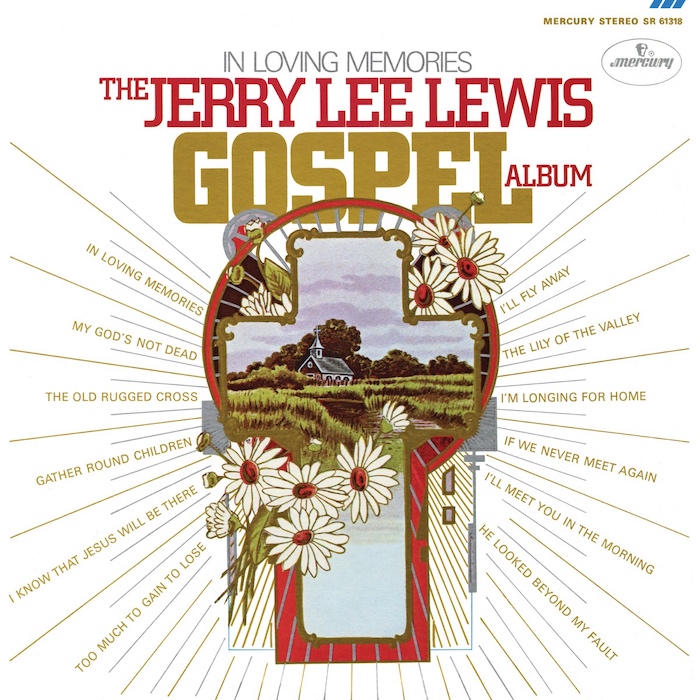

The tale has survived countless retellings since its occurrence in October 1957 because it speaks so directly to the tension between rock’n’roll and religion that drove many of our favourite artists here at Vintage Rock. Jerry Lee, Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Johnny Cash, all raised in religious households, released gospel records at the pinnacles of their fame and fortune. In fact, these Southern titans’ greatest gospel albums – Elvis’ His Hand In Mine, Little Richard’s The King Of The Gospel Singers, In Loving Memories: The Jerry Lee Lewis Gospel Album and Hymns By Johnny Cash – arguably stand among their finest LPs.

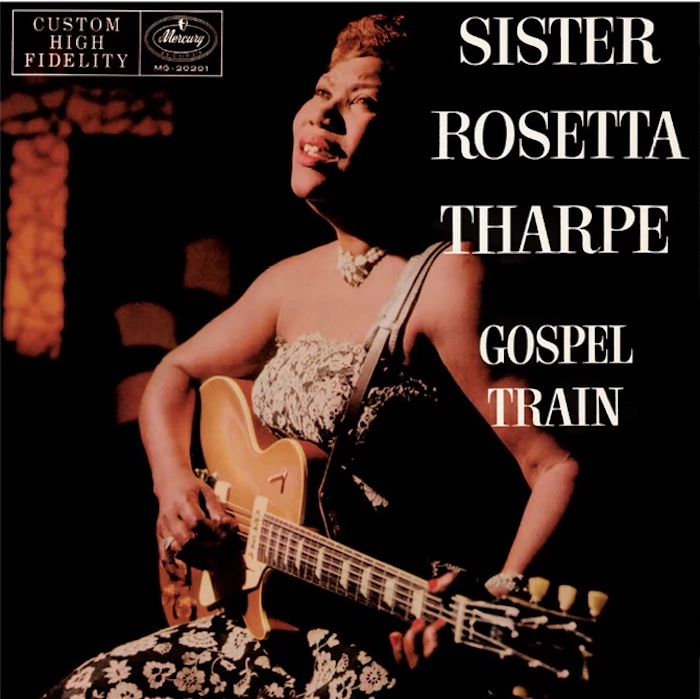

However, when it comes to reassessing the work of rock’n’roll legends, their religious records are often overlooked. Writing in The Guardian about Little Richard’s passing in 2020, the critic Tavia Nyong’o lamented “the almost universal dismissal of [his] gospel output by rock critics”. Gayle Wald, author of Shout, Sister, Shout!: The Untold Story of Rock-and-Roll Trailblazer Sister Rosetta Tharpe and an expert on gospel’s influence on rock’n’roll, tells Vintage Rock: “There has always been this tension between certain rock fans or critics and the gospel music that many of the rock artists love and grew up with.”

Heaven’s Karaoke Booth

Wald speculates that this is partly related to “the musical categories, the [idea that] gospel and rock are somehow separate, and when they do one, they’re not doing the other… I think it makes [fans or critics] uncomfortable to the degree that people think of rock’n’roll as rebellious and implicitly full of social commentary through its rebellion, [while gospel] seems to be about belief and faith and appears that it’s in tension with that.”

Our rockers’ stints in Heaven’s karaoke booth might not, on the whole, have set the charts alight, but let’s look on the bright side. While classic rock’n’roll records are by now widely familiar after years of enjoyment, this leaves some absolute gems ready to be rediscovered. From the King’s silky smooth Milky White Way and through to Little Richard’s sneakily rebellious Joy, Joy, Joy, it’s enough to make you throw your hands up and proclaim: ‘Praise be!’

Gospel and rock’n’roll go back a long way, of course. In Honkers And Shouters: The Golden Years Of Rhythm And Blues, Arnold Shaw noted: “Despite the long-standing conflict between blues as ‘devil songs’ and gospel as ‘God songs’, there is a root link between Black religion and blues singing.”

Wald, meanwhile, feels it’s significant that Jerry Lee, Little Richard, Elvis and Johnny Cash all visited Pentecostal churches at formatives ages: “The music was already drawing from secular sounds… It was rhythmic and lively and fast and loud.” She also notes that Pentecostalism “is about the personal relationship with God, and having an experience of the holy spirit is about personal access to God, and intimacy”. Perhaps, then, our iconoclastic stars felt enabled to live outside of the realms of normal life because the Lord himself had ordained it: “Like, God touched you and this is what you did.”

Touched By God

Indeed, Presley’s cousin Billy Smith once recalled that the Pentecostal church was such a major influence on Elvis that he would often stand in awe at services, almost mystified by the music. As a child, the King would sing gospel songs with his mother and father; the latter had been a deacon. But it was at Memphis’ East Trigg Baptist Church that the young Elvis witnessed the Black gospel choirs that influenced his own music, as he fused its soulfulness and vocal acrobatics with the countrified style that was more expected of a white performer at the time.

Several hundreds of miles away in Macon, Georgia, a young Little Richard found his feet with the Tiny Tots, a children’s gospel group who praised the Lord across the state. Johnny Cash, meanwhile, saw a darker side to the religiosity that helped to shape him. “The first preachers I heard at a Pentecostal church in Dyess, Arkansas, scared me,” he once wrote. “The talk about sin and death and eternal hell without redemption, made a mark on me. At four, I’d peep out of the window of our farmhouse at night, and if, in the distance, I saw a grass fire or a forest fire, I knew hell was almost here.”

Higher Calling

Worshipping At The Altar Of Rock’n’Roll

Spreading The Word

God’s Jukebox

Similarly cowed by his own transgressions, Lewis slipped a coin in God’s jukebox in 1971. Lewis’ marriage to his cousin Myra Gale, which had destroyed his career in 1958, hung by a thread. Finally sick of his commitment to booze and drugs and other women, she filed for divorce.

In Great Balls Of Fire: The True Story Of Jerry Lee Lewis, a book penned with Myra, co-author Murray Silver wrote that the singer was so lovesick he vowed to see the light: “[Jerry] pledged never to look at another woman, drink another drop or pop another pill. He’d even give up rock’n’roll, for God’s sake, if only she’d come back.” For once, the Killer came good on his promise, and the result was In Loving Memories: The Jerry Lee Lewis Gospel Album, which also features The Jordanaires.

By the time of its release, Lewis had reinvented himself as a successful country singer, and the LP’s woozy slide guitar and lolloping rhythms do little to mess with the formula; other than their lyrics, these songs could nestle on any of the four – yes, four – albums he released that year. And even then My God’s Not Dead, a spin on a hymn, drips with sarcasm.

He might have had the “Devil” in him, but In Loving Memories… showed a more vulnerable side to the Killer – and the same went when all of our rock’n’rollers made great gospel records. It’s natural, comments Wald, that “famous artists under incredible stress would keep searching and land back on things that had once served them… That just makes sense from a human point of view.” And whether you’re religious or not, it’s this very humanity that makes them worthy of a little worship.

Subscribe to Vintage Rock here

Read More: Songs Of Praise – Elvis’ gospel music