With his motorvatin’ debut hit, Maybellene, Chuck Berry combined country and blues, resulting in a song that raced towards the future. As the pioneering classic turns 70, we declare: “Hail! Hail!”

Words by Jordan Bassett

Back in August 1955, Charles Edward Anderson Berry, a 28-year-old aspiring hairdresser who worked for his father’s construction company, heard a song playing from a radio in a tailor’s shop. It was the sound of something brand new, with a crunching guitar riff and gleefully made up words (“As I was motivatin’ over the hill/ I saw Maybellene in a Coupé de Ville”) thrown together in a style that was neither country nor R&B – yet somehow both. The song gleamed with promise, filling the airwaves like the revved engine of a Cadillac adorned with tailfins and bullet taillights.

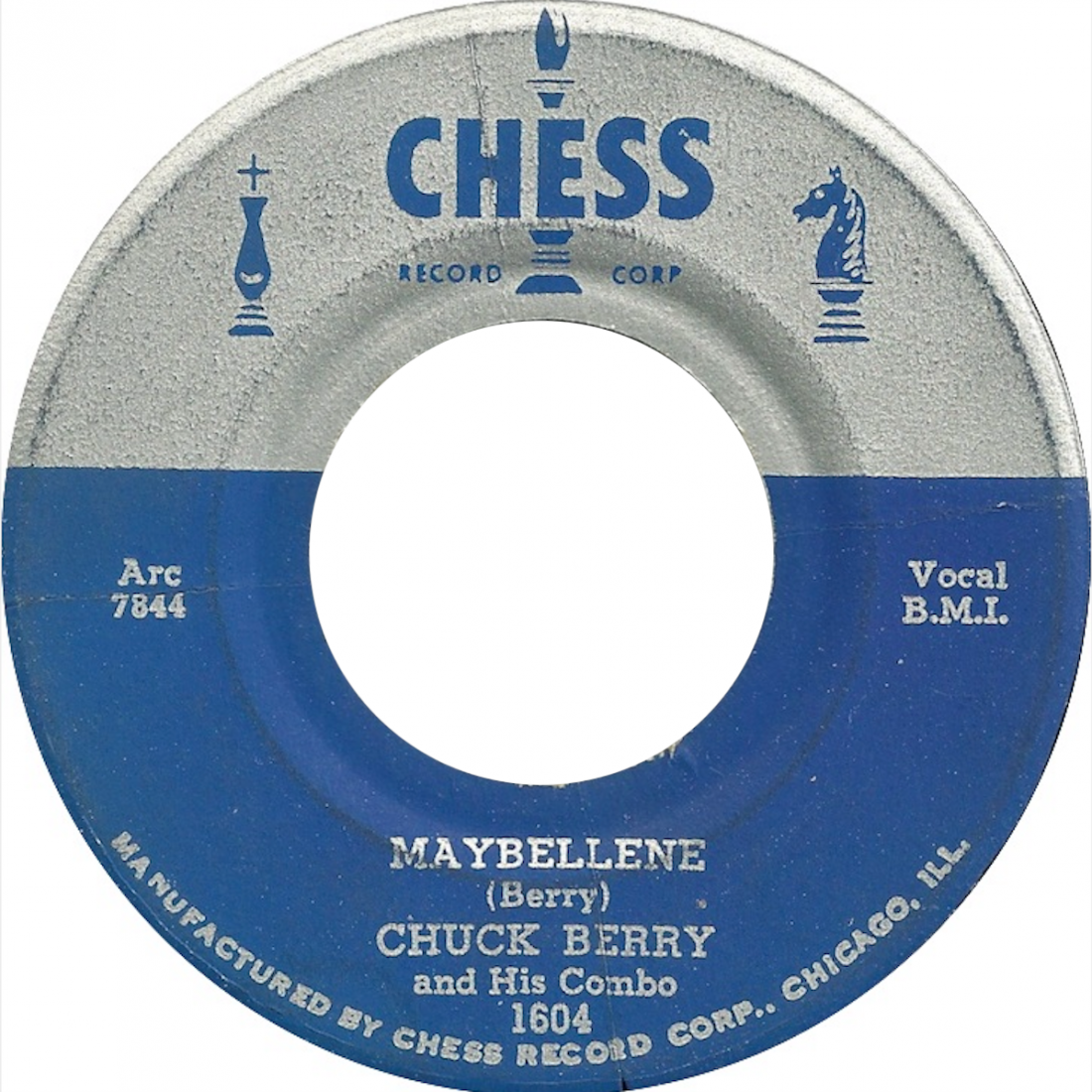

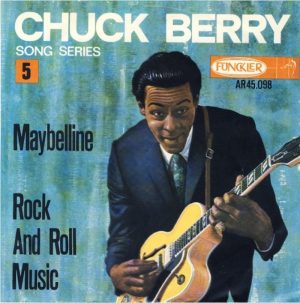

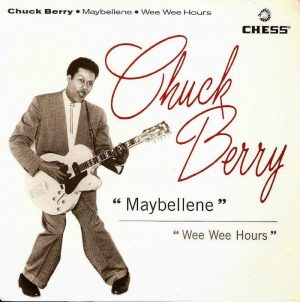

Chuck Berry had, of course, heard his own song, Maybellene, his spectacular debut single on Chess Records. The man who would come to be known as the Poet Laureate Of Rock’n’Roll raced about 20 blocks to excitedly inform his relatives that he’d heard his single out in the wild.

It was the start of an incredible journey that would take him from obscurity to the top of the charts, from prison to the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame, an odyssey that would encompass acclaim, controversy and influence pop and rock music forevermore. Seventy years since it was recorded, Maybellene still absolutely moves.

Teen Spirit

Lyrically, it may be a lament about a broken heart, with its famous opening line asking the titular object of Chuck’s affections “why can’t you be true?”, but the song’s tone is unmistakably celebratory. Really, the star of the track is the glimmering Cadillac that the narrator lusts after almost as much as the woman that’s inside it. Musically, of course, the song sounds like an all-American automobile, the percussion thumping like pistons and that riff racing off into a bright new future.

When the laureate died at the grand old age of 90, his biographer, John Collis, explained on the BBC radio show The Documentary: Chuck Berry 1926-2017: “He was the first to realise there was a new commercial market in the mid-50s: the teenager… The teenager doesn’t just define an age group; it defines an economic force. And, of course, that couldn’t have happened before the mid-50s because America was recovering from the war and in 1954 it recovered economically.

“There was a consumer boom following this. Cars got sexier: they were not just functional; they were good-looking. And Chuck Berry was the first, I think, to latch on to this.”

Ironically, Berry’s forward-thinking paean was rooted in the past, given that he based the composition on the traditional western swing song, Ida Red.

One of six siblings, he’d grown up in a relatively salubrious St. Louis, Missouri, neighbourhood known as the Ville, his father a Baptist church deacon and his mother a school principal. The trappings of middle-class life enabled him to explore his interest in music, but weren’t enough to save him from a three-year prison sentence in Jefferson City for armed robbery. During his sentence, he joined a gospel group so accomplished that they were permitted to perform outside the jail.

Poet Laureate

Thus commenced Berry’s career as a performer. On the outside,in 1953, he joined blues pianist Johnnie Johnson’s Sir John Trio on guitar and soon became the main attraction at St. Louis’ Cosmopolitan Club, where they rocked the crowd with their rendition of Ida Red. During a segregated show at the Duval Armory in Knoxville, Tennessee, the singer recalled in his 1986 memoir, Chuck Berry: The Autobiography, that the band stormed through the track and he hammed it up with some ad-libbed “Southern country dialect”.

The response surprised him: “Contrary to what I expected, I received far greater applause from the white side of the ropes than the Black side, where I received only a chuckle or two.” As he noted with anthropological curiosity rather than ruefulness, it was a sign of things to come.

Get The Girl

Ida Red, a song of unknown origin, had originally been made famous by Bob Willis and his Texas Playboys in 1938. Traditionally, the lyrics in the verse would change according to who was performing it, though the chorus would always be on the dream girl at its centre, with a variation on the lines Willis opted for: “Ida Red, Ida Red/ I’m a plumb fool ’bout Ida Red.”

For his version, Berry changed the central lyric to “Ida Mae” and incorporated a little personal experience. “The body of the story of Maybellene was composed from memories of high school and trying to get girls to ride in my 1934 V-8 Ford,” he wrote in his autobiography, explaining that he allowed American football aces to drive girls around in his ride and even bought seat covers for them to use.

This seems a generous move for a man who was famously guarded when it came to his personal finances. Sure enough, his true feelings about the arrangement were revealed in lines that he eventually excised: “I saw pretty girls in my dream de Ville/ Riding with the guys, up and down the road/ Nothing I wanted more’n to be in that Ford.” Racily, Berry added: “Oh pretty girl, why can’t it be true… You let football players do things I want to do.”

Trailblazing Talent

Berry crafted a comical narrative about a man trying to keep up with the Cadillac-driving woman – no mean feat, since he’s in a dusty old Ford. That V-8 engine had been revolutionary back in 1932, when Henry Ford triumphed in producing a speedy engine that was light and cheap enough to be fitted in an affordable car. By the mid-50s, though, Chuck wanted more: a life of affluence and excitement that was represented by the Cadillac Coupé de Ville.

Five years on, when he had achieved fame and fortune, the rock’n’roll pioneer adorned the song’s live version with new lines, which see the Cadillac catch up with him at the bottom of a hill: “Me and that Cadillac was neck and neck.”

In hot pursuit of this new life, in May 1955, he set out to see his hero Muddy Waters perform in Chicago. After the show, Berry hung about, collared the star and asked for an autograph. He then posed the question that changed history: “How do you get in touch with a record company?” Amiably, Waters replied: “Why don’t you go see Leonard Chess over on 47th?”

My Kind Of Town

The bluesman had recorded with Chess Records (then Aristocrat) since 1946 and his act of generosity mirrored that of Specialty Records’ Lloyd Price, who was accosted by Little Richard in much the same manner. Mr. Personality advised the Georgia Peach to contact his own label boss, Art Rupe, a link-up that resulted in another 1955 musical atomic bomb, Tutti Frutti. Just like Richard, Chuck submitted a scratchy demo to the man who would make him famous.

It was enough to pique Chess’ interest and Berry was soon invited to the Windy City’s soon-to-be legendary Universal Recording Corporation studio.

Berry was astounded at what he considered to be the studio’s lushness. It was around 20 feet wide and 50 feet long, containing a baby grand piano, a dozen microphones and a pile of throw rugs. He’d used just one microphone for his demo, but utilised eight for his sessions with Chess; already he was in a different league. In a small anteroom, Leonard Chess operated the Ampex 403 tape recorder and beadily watched Berry through the glass, making suggestions with his brother and label co-founder Phil.

This first session was an education. “I was familiar with moving in and away from the microphone to project or reduce the level of my voice,” Chuck wrote in his memoir, “but was not aware that in a studio that would be done by the engineer during the song.”

Burning Ambition

For all his naivety, Berry seized the opportunity with all the burning ambition that had brought him here. Assisted by Johnnie Johnson and Sir John Trio drummer Ebby Hardy, as well as Chess-appointed bassist Willie Dixon – a blues legend in his own right – the singer then set about recording not one but three rock’n’roll classics. They also cut the gorgeous, bluesy Wee Wee Hours, which Berry had expected to be the most interesting to the blues-focused Chess.

Instead, it was Chuck’s take on Ida Red that enticed the bosses. If Hardy’s steady percussion dominates the track, it’s perhaps because he played into three microphones, while the other musicians only had one each. Berry, meanwhile, sat down to record his vocals simply because there was a chair in the room and, due to his inexperience, he thought he’d been ordained to make use of it.

How many classic rock’n’roll vocals have been cut while their singer assumed a relaxed position? Having knocked out some of the greatest rock’n’roll songs ever recorded, they ordered burgers and sodas. Ever with a beady eye on the finances, Berry noted with glee that Leonard picked up the tab.

Joy Ride

They rattled through 35 attempts at Maybellene before Leonard Chess was satisfied that they’d captured the perfect take, though Chuck himself had considered many of the previous versions to be suitable. Whatever Chess heard in that 36th take, the final single is hardly perfect by today’s standards. After a raucous guitar solo, Berry barrels back into the verse, cheerfully oblivious to a strange fuzziness that has crept into the recording.

Naturally, though, it’s these imperfections that make the song so thrilling. And that wild solo was bound to knock the recording sideways. “The rock’n’roll guitar was supposed to be a rhythm instrument, polite and unobtrusive,” Jesse Wegman wrote for NPR in 2000, “but a little over a minute into Maybellene, Chuck Berry, wielding his yellow Gibson ES-350T, shattered that image forever.”

Motivatin’ Music

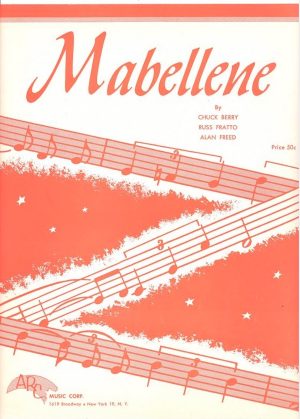

At two minutes and 20 seconds, Chuck’s perfectly imperfect little tale was ready to take on the world. There was only one problem. Leonard Chess was concerned that the title, Ida May, might cause a copyright headache through its similarity to Ida Red.

Berry later claimed he came up with the new one on the spot, inspired by the name of a cow in a book he read as a child.

Johnnie Johnson, though, recalled things differently, telling NPR: “We looked up on the windowsill, and there was a mascara box up there with Maybellene [sic] written on it. And Leonard Chess said, ‘Why don’t we name the damn thing “Maybellene”?”

However they got there, the song wasted no time in zooming up to No.1 on the Billboard R&B chart, before crossing over to No.5 on the pop parade. Like those revellers at the Duval Armory in Knoxville, white teenagers responded immediately to the sense of promise built into Maybellene. The previous year, Elvis caught their imagination as a white musician performing a Black blues song, Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup’s That’s All Right, Mama. Here, as a Black man taking on what was essentially a fuzzed-up country song, Chuck reversed the formula.

Game Changer

The barriers were already disappearing into the rear-view mirror when Berry put the pedal to the metal, musically speaking. New York’s infamous DJ Alan Freed played Maybellene for two hours straight on his WINS show – just as Memphis disc jockey Dewey Phillips had spun Elvis’ That’s All Right 14 times back-to-back in summer 1954.

Chuck speculated that the song was so popular with white listeners because they could understand his diction more clearly than other Black performers; Johnson recalled some fans’ surprise that Berry himself was not white.

No wonder R&B superstar Beyoncé sampled Maybellene on her boundary-breaking 2024 country-inspired album Cowboy Carter. Chuck sensationally took a country standard and contorted it into something shinier, faster and more aspirational.

In Mystery Train, author Greil Marcus noted that country was often about accepting life’s hardships, while rock’n’roll represented the chance for a better life.

As he skipped away from that tailor’s shop, having heard his own tune – Chuck Berry moved towards a wider vista for himself and all those who followed.

Read More: Classic Album – Chuck Berry Is On Top