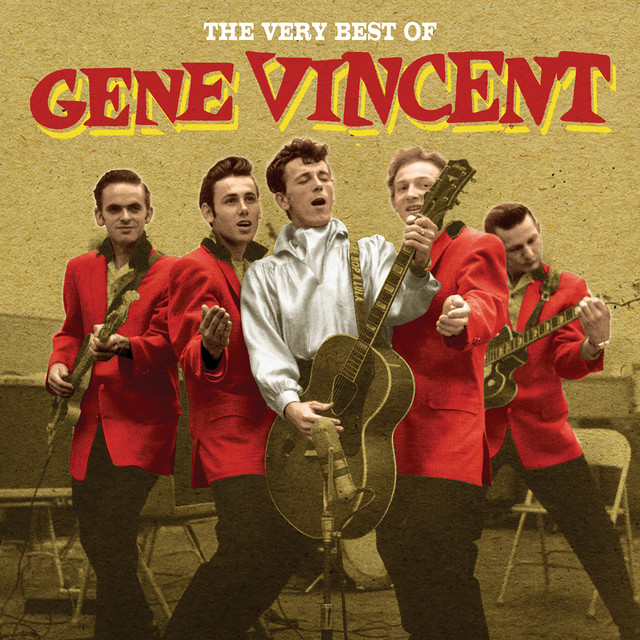

When rock’n’roll’s popularity began to fade in the US, the legendary Gene Vincent made the UK his new home. With the help of Matchbox’s Graham Fenton, Vintage Rock charts Gene’s later years of triumphs, plenty of tragedy and an indelible mark on a generation of rockers… By Jack Watkins

The words saint and Gene Vincent aren’t often seen together, but if ever there was a lead contender for the title Patron Saint of British Rock’n’Roll, it has to be the man born Vincent Eugene Craddock, in Norfolk, Virginia in 1935.

In the dog days of the 1960s when rock’n’roll was considered old hat, Vincent, who spent so much time living in and gigging up and down the UK and on the European mainland, became like an unofficial spokesman for the cause. He became a flag-bearing hero for fans and an inspiration for a generation of European musicians.

Two of Britain’s best pre-revival rock’n’roll bands of the late 60s and early 70s, The Wild Angels and The Houseshakers, backed him on a couple of his last tours, learning from him at the same time as watching in dismay at their idol’s worsening mental and physical state.

One man who connects that era to the present-day rockabilly scene is Graham Fenton. While best known as the lead vocalist of the hitmaking rockabilly band Matchbox, Fenton is also a former member of The Houseshakers, with poignant memories of Vincent’s last days in the UK.

In the years since his hero’s death in 1971, Graham has subsequently recorded a lot of material which has recreated or reinterpreted the Vincent sound, including the albums A Tribute To Gene Vincent and Shades Of Gene, released by Graham Fenton’s Matchbox in 1993 and 2000 respectively.

In the early 1990s, when the 1958 line-up of Vincent’s Blue Caps reformed for a European tour, he was chosen to share lead vocal duties because of his faithfulness to the Vincent style. His annual Gene Vincent tribute nights at the famed 60s rockers’ haunt, the Ace Cafe, just off London’s North Circular Road, have been another contribution to keeping the candle burning for the Screaming End.

Meeting up to reminisce at the Ace, West London-born Fenton says he first saw Vincent perform in February 1964. “A friend of mine said he was playing at the Hounslow Baths. In the winter when the swimming pools shut, they’d board them over, making it like a big hall.

“So we were standing on the top of a swimming pool with a stage at the end. Gene was backed on that tour by an English band, The Shouts. We were standing at the back, and I remember Gene brushing past us in the beige camel jacket he used to wear at that time. I’d never seen someone like that, banging the mic stand and throwing it up in the air!”

In fact, the year of 1964 came towards the end of a run that had seen ‘Sweet Gene Vincent’ achieve levels of popularity in Britain, France and Germany that arguably exceeded anything he had ever achieved in the States.

It had started at the end of 1959 when, with the hits and live dates having dried up in his homeland, Vincent agreed to come to Britain to appear on the Jack Good-produced, Marty Wilde-fronted TV show Boy Meets Girls. On first sighting, Good had been dismayed by Vincent’s appearance after he’d touched down at London Airport.

“The image young people who never saw Gene when he was alive have, is this rebel figure with his collar up, mean and moody,” says Fenton. “But he wasn’t really like that. It was Jack Good who put him in leathers. When you see his early clips with the Blue Caps, he hasn’t got leathers on, but he’s wild. But when Jack Good first met him, he found this guy of average height, mild-mannered, pleasant and quiet-spoken. He was like a Southern gentleman, a bit square; ‘Yes, Mr Good’ and all that. Good thought: ‘I can’t have this!’ He had a vision of Vincent as a tragic Shakespearean character.”

And so the idea of the supercharged rocker with the leather-boy image, hunched over a microphone, swivelling round and staring dementedly at the ceiling with those big expressive eyes, was conceived.

But Vincent was a genuinely tortured soul. The pain from a leg injury sustained in a motorcycle accident when in the Navy in 1955 which forced him to wear a brace, never left him. Even if Good envisioned using the infirmity as a gimmick, well before the end of his career Vincent was a real tragic anti-hero.

“I saw Gene’s leg once,” remembers Fenton. “It was thin and withered. A pretty grim sight. With technology today and the prosthetic legs, he’d have been bopping around. But back in the 50s, they wanted to amputate his leg and replace it with a tin one and he’d pleaded with his mother: ‘Don’t let them take my leg away!’

“Rather than have it removed he suffered with extreme pain for the rest of his life. The Blue Cats told me he never rested it after he’d had the accident, and was always taking painkillers. Of course, it ulcerated and got worse.”

It might not just have been pain that caused his paranoiac, self-destructive tendencies, though. The recently deceased Chas Hodges reckoned he couldn’t handle stardom, that he preferred to be one of the boys. Did he have low self-esteem? “I think that was why he drank,” reckons Fenton. “Of course, he drank partly because of the pain in his leg, but it also gave him a bit of extra confidence to go on stage.”

He recalls that there may have been a bit of friction between him and Tommy ‘Bubba’ Facenda, one of the legendary Blue Caps Clapper Boys. “Tommy was a sharp-looking Italian-American boy, better looking than Gene. Gene didn’t say anything but it upset him the way the girls loved him. Tommy upstaged him for a while. They never argued about it, but by 1958 they had started to drift apart.”

Chas Hodges saw the alcoholic, self-destructive side of Vincent when his band The Outlaws backed him on his 1963 tours. But in 1969, when a BBC crew were on hand to film the documentary The Rock’n’Roll Singer, Gene seemed like the subdued, quiet-spoken guy Good had met in 1959.

The grainy film is heartbreaking to watch, reflecting an artist who, backed by The Wild Angels, was still delighting his fans with committed live shows, but then undergoing the humiliation of having to hang around backstage for payment. This was no way to treat a star.

Among several moving sequences in the film is a segment of him limping down the street alone at night, taking in the lights of London’s West End while the soundtrack plays one of his most recent recordings, a cheery reworking of Ernest Tubb’s country No. 1 from 1946, Rainbow At Midnight. Somehow, in spite of everything, Gene Vincent was still believing.

By 1970, it was The Houseshakers who were backing him, a band fronted by Graham Fenton, still cutting his teeth as a young rock’n’roll vocalist, with Terry Clemson, formerly – as Terry Gibson – of The Downliners Sect, on lead guitar. Fenton comes from a musical family, his father being a crooner before he got his call-up papers in the Second World War, and brother Ken a jazz-loving bass player who worked with Don Lang and Rick Wakeman.

With a background like that, Fenton appreciated Vincent’s vocal versatility which went beyond that of your average rocker. “His style was unique, and he kind of took me under his wing, told me to put as much as you could into an act, to really put on a show and try to overcome my nerves.”

As the proud owner of a 1959 Chevrolet Impala, Fenton also found himself on chauffeur duties, even driving his fellow bike enthusiast into the Ace Cafe forecourt before taking him back to meet his mum at his home in Hanwell. “Gene just said: ‘Pleased to meet you, ma’am, your son’s doing well.’ So polite! He had spent so much time in this country by 1970 he had developed a lot of Anglicised phrases which used to make me laugh. He could be terrifying, but only when he got pissed.

“We thought he was going to die in the back of my Chevy at one point when he started coughing up blood. We tried to take him to the hospital, and I remember him growling: ‘If you take me in that goddam hospital, the tour’s over.’ He’d have these flare-ups, but it was managers, agents and promoters he didn’t get on with. He was uppity with them, he’d got so badly ripped off.”

Fenton saw Vincent one last time weeks before he died, when he came back to London for an alimony court case in September 1971. “He’d called our manager Earl Sheridan and said he’d like to tour with the boys [The Houseshakers] again, but he’d so insulted Sheridan on the previous tour, he just said: ‘I don’t even want to speak to you, you get someone else.’

“If Gene had spoken to us direct, we’d probably have done it. So he ended with a pick-up pop band, Kansas Hook. He was so ill and drinking heavily by then the shows fell apart. But I was driving through Perivale in my Chevy, when this little Austin pulled up beside me at the traffic lights.

“Gene was in the passenger’s seat and, recognising my car, rolled down the window and called over: ‘Hey man, how’s it going? No hard feelings, shame I couldn’t work with you this time.’ The lights changed, his car went one way, I went the other.

“Three weeks later I heard on the radio he’d passed away from a haemorrhage at his parents’ house in California. I know he was ill, but with the stress of the court case, he was probably drinking more, maybe taking more aspirin for his leg and, bang, something had to give.”

Johnny Meeks, second only to Cliff Gallup in the roll call of Vincent’s greatest guitarists, attended Vincent’s funeral. “The family was arguing, but apart from that Johnny said there were only about three other people there,” recollects Fenton. “He said it was like a pauper’s funeral. Well, I finally made it to the cemetery in 2001.

“His grave is near the San Fernando Highway and the headstone is quite eroded. I took some flowers and just said: ‘This is the only way I know how to say goodbye. Thanks for being a friend.’ The superintendent lady there said it was now the most visited grave in the cemetery. And yet there had been virtually no-one outside family to see him buried at the ceremony.”

Even though a couple of tracks Vincent recorded at Morgan Studios in Willesden with The Houseshakers (a re-recording of his classic, yet unaccountable 1958 flop single Say Mama and Hank Snow’s I’m Movin’ On for an album The Battle Of The Bands on one of his off days) suggested a voice shot to bits: other recordings he made nearer the end, including an incredible home recording The Rose Of Love for Ronnie Weiser in Los Angeles just two months before he died, show he was still able to cut it, with all the old vocal touches intact. Like his old mate Eddie Cochran, Vincent died still having so much more to give.

In subsequent years Fenton not only performed with the Blue Caps, but became friends with drummer Dickie Harrell, plus the Clapper Boys’ Tommy Facenda and the late Paul Peek. He even met up with Ken Nelson, the producer of Vincent’s Capitol recordings.

“I was with the Blue Caps and it was a very emotional occasion for them because they hadn’t seen Ken in years. They were still calling him ‘Mr Nelson’. He was a sweet old guy. He was 93, and he lived to be 96. He had to put his hearing aid in but his mind was still really sharp.”

Today, younger British rockabilly bands are still drawing inspiration from the music of Vincent. At the time of speaking, Fenton was looking forward to going into Sugar Ray’s vintage recording studio in Essex to put down the vocals for an album of Cliff Gallup-era Vincent numbers with the band Race With The Devil.

“People who never saw him are still discovering Gene’s music and when they realise those Capitol recordings were made as long ago as 1956 they know the sound on them is phenomenal. I think Gene Vincent is probably bigger now than when he was alive.”