More than six decades after Johnny Burnette scaled the charts with Dreamin’, his son Rocky Burnette and nephew Billy Burnette discuss the life, death and lasting influence of one of the architects of rockabilly… By Douglas McPherson

Like so many of the original rock’n’rollers, Johnny Burnette’s career was cut short by tragedy. At the time of his death in a boating accident in the summer of 1964, the handsome singer was best known for the smooth and catchy, string-laden teen pop hits Dreamin’ and You’re Sixteen. However, the mark he left on music was far wider and deeper than that.

Before his success as a solo artist, Johnny and his brother Dorsey wrote a string of hits for Ricky Nelson, including Waitin’ In School, Believe What You Say and It’s Late.

And before that, the Burnette brothers teamed with guitarist Paul Burlison and created one of the most incendiary caches of rockabilly music ever recorded, as Johnny Burnette and the Rock ’n roll Trio. Drenched in echo, driven by Dorsey’s slap bass, shot through with Burlison’s lightning-bolt guitar licks and peppered with Johnny’s wild yells and screams, songs such as Tear It Up, The Train Kept A-Rollin’ and Eager Beaver Baby remain unsurpassed examples of the genre.

The only trouble was, the songs were too wild for mid-50s America and never scratched the charts. It was only 25 years later, when the Stray Cats spearheaded a rockabilly revival (and covered the Trio’s Your Baby Blue Eyes almost note for note) that fans began to realise that the Burnettes were the ones who started the whole thing.

“My dad and Dorsey didn’t clean up their lyrics the way Elvis did,” says Johnny’s son, Rocky. “They didn’t say, ‘I wanna play house with you’. They said, ‘I wanna make love with you’. Train Kept-A-Rolling was about two people making it in the back of a train.”

“They were banned just about everywhere,” confirms Dorsey’s son, Billy. “When I started doing that stuff again in 1980, everybody thought it was punk music.”

The wild ones

Johnny Burnette was born in Memphis on 25 March 1934, a year and three months after Dorsey, who arrived on 28 December 1932. As infants, they were each given a guitar by their father one Christmas. According to legend, they responded by immediately smashing the instruments over each other’s heads, and a fondness for violence never left the brothers, who grew up as keen on boxing as they were on music. In fact, it was at a boxing tournament that Dorsey met another pugilist, Paul Burlison, who joined them in their first band, a country and bluegrass outfit called Johnny Burnette and his Rhythm Rangers.

The group released an up-tempo country rendition of Dorsey’s song, You’re Undecided on the Von label as early as 1953, although different sources give later dates. Credited only to Johnny Burnette as artist, the single is not to be confused with the Trio’s later echo-drenched rockabilly version.

The Burnettes lived in Lauderdale Courts, a low-income federal housing project where the concrete walls of a laundry room provided the perfect echo for rehearsals. A frequent visitor to their sessions was Elvis Presley, who lived in the same development. And, according to the Burnettes, it was there, not at Sun Records, that rockabilly was born.

“In my book, Crazy Like Me, I have a picture of my dad and Elvis standing out front of Lauderdale Courts,” says Billy. “It’s the Boys Club and my dad is standing right next to Elvis in a group shot in, I think, ’52 or ’53. My mom lived across the street and she used to play basketball with Elvis when they were teenagers. A lot of people dismiss the influence of the Burnettes on Elvis, but he got a lot of his ideas from those guys.”

Jerry Naylor, who took over as the lead singer with the Crickets following Buddy Holly’s death, claims that rockabilly was named after the Burnettes’ sons Rocky and Billy, who were born in consecutive months in 1953.

According to Naylor‘s book The Rockabilly Legends: They Called It Rockabilly Long Before They Called It Rock and Roll, the brothers would dedicate a number to their sons and introduce it with “Here’s a Rocky ’n’ Billy song…” before writing Rocky ’n Billy Boogie, which became Rock Billy Boogie. It’s a good story, but Rocky is reluctant to endorse it.

“Paul Burlison used to tell that story, but I can’t…” He sucks his teeth. “When Paul said that to Dorsey, Dorsey said, ‘Aw, I don’t know…’ It’s one of those stories. As the years went by, in the 60s and 70s, you’d be surprised how many people would tell Johnny and Dorsey Burnette stories.”

Rocky goes on to tell one about Roy Orbison visiting the Burnettes at the famous Peabody Hotel in Memphis. “Roy pushed the elevator button, the door opened and my dad and Dorsey were down on the ground fighting with each other. The Peabody ducks were walking past and everything!” he recalls with a laugh. “My dad was the spark plug,” Rocky adds. “He would start it, then Dorsey would finish it, because my dad wasn’t half the size of Dorsey. Dorsey was 6’2″ and he was a professional fighter, and my dad was four or five inches shorter.”

Early smashes

After leaving high school, Dorsey and Burlison became electricians at the Crown Electric Company, where Elvis drove a truck, while Johnny became a barge hand on the Mississippi.

Johnny also teamed up with his country music namesake, Johnny Cash, to sell ‘unbreakable’ plates door-to-door.

“Cash sold one to his parents and my dad sold one to my grandmother and that was it,” Rocky chuckles. “So Cash says, ‘Let’s work together. When the lady comes out I’ll say, ‘Have you ever seen anything like this?’ Then you drop the plate and when she sees that it doesn’t break we’ll sell some to her’.

“So they go up to a house in South Memphis. Cash says, ‘How would you like something like this?’ My dad dropped the plate and it busted into 10 pieces! The lady was like, ‘You boys get out of here!’.

“After that, my dad said, ‘I know a guy that’s selling televisions. Let’s sell some televisions’. So once again, Cash’s family bought one, my family bought one and that’s all they were able to sell. They said, ‘To hell with it, let’s just try to get some more gigs’. About six months later, Cash was a big star.”

Tearin’ it up

When Elvis signed to Sun Records, the Burnettes auditioned, too, but were told they sounded too much like Presley. Undaunted, they headed for New York, where they became three-time winners on Ted Mack’s The Original Amateur Hour, a nationally televised talent show that was the X-Factor of its day. Their success on the show won them a deal with Coral Records.

“Capitol also wanted to sign them,” Rocky reveals, “so when they told Capitol they were going with Coral, they said, ‘But we’ve got a friend called Gene Vincent who’s incredible’. They were always helping people and were instrumental in getting Gene a deal.”

Ironically, it was Vincent’s career that took off, with Be-Bop-A-Lula, while a handful of singles from the newly-named Johnny Burnette and the Rock ’n Roll Trio’s one self-titled album failed to find more than regional success.

If the Burnettes were wild, then their pal Gene was wilder, says Rocky.

“He’d get Dorsey, Paul and my dad in a lot of trouble. The wives didn’t like him because every time Gene showed up they knew there was gonna be trouble. Gene was gonna take ’em out and do that wild stuff he did. He had a lot of James Dean in him.”

Other close friends of the Burnettes included the bass-playing brothers Johnny and Bill Black, who also grew up in Lauderdale Courts.

“Johnny was going to be the original bass player for Elvis,” says Rocky. “When Elvis was told Sam Phillips wanted him to go in and record some stuff he said, ‘Let me call Johnny to play bass’. Bill answered the phone and said, ‘Johnny’s in Texas, helping my grandmother with her roof, but I’ll come down and play with you’. So that’s how Bill got the gig with Elvis instead of Johnny.

“Later on, Johnny Black was in the movie, Rock, Rock, Rock!, playing bass for the Rock’n’roll Trio instead

of Dorsey. Oh man, Dorsey and my dad didn’t talk to each other for a year after that!”

Another bone of contention for Dorsey was his brother’s prominent billing.

“My dad actually quit the band because he wanted to keep calling it the Rock ’n Roll Trio,” says Billy. “Then somebody at the label or whatever said, ‘let’s call it Johnny Burnette and the Rock ’n Roll Trio’. That pissed my dad off.”

Rockin’ with Rick

The siblings reconciled when the Trio recordings failed to yield a hit and Dorsey invited his younger brother to relocate with him to California and pursue a new career as songwriters.

The tough guys, who Elvis had nicknamed the Daltons after one of America’s most wanted gangs, took an aggressive approach to pitching songs. They lay in wait outside Ricky Nelson’s house and ambushed the young singer

when he returned home. Dorsey pinned him to the lawn while Johnny began singing with his guitar.

The approach worked and Nelson was soon enjoying a string of Burnette-penned hits, including Waitin’ In School (No.18), Believe What You Say (No.8), It’s Late (No.9) and Just A Little Too Much (No.9).

Rocky remembers the day Johnny and Dorsey went to collect their royalty cheques. “The wives were so excited, because the cheques were like $20,000 apiece and these were country boys who were used to making $50 or $100 a week. That night, we all waited up for them to come back with the dough… and they never came home.

“We waited all the next day. By now, the wives were crying and my grandmother was pissed off, saying, ‘Wait until I get a-hold of them boys!’

“It’s about dark and here they finally come. They both drove up in two brand new Cadillacs. My mother, grandmother and aunt were fit to be tied, they were so upset. Back then, you could get a Cadillac for $4,000 or $5,000, but that was still a big chunk out of their pay. But they were typical country boys: get rich, buy Cadillacs!”

Speaking of Nelson reminds Rocky of the day that the singer met Johnny and Dorsey’s father. “My grandfather got his hand cut off in the coal mines. He actually got it cut off by a coal cart while pushing another guy out of the way and saving his life.

“He was left with a portion of his index finger and thumb, and it was like a lobster claw.

“One day, we were having Sunday dinner and grandpa says, ‘You boys never take me over to Ricky Nelson’s house. Are you embarrassed by me because I’m handicapped?’ They said, ‘No, Daddy,’ and they took him right over.

“They told Ricky, ‘This is our dad, Dorsey Sr, and he really wanted to meet you’. Grandpa stuck out that lobster claw and they said Ricky turned white as a ghost!”

In 1980, when Rocky released his hit single Tired Of Toein’ The Line, Nelson repaid him with a favour for the songs Johnny and Dorsey had written for him.

“Rick Nelson was the sweetest guy I ever met,” says Rocky. “He cut Tired Of Toein’ The Line before I did and it was going to be his single. But when he heard that I had a hit going up the charts in England and that it had been a No.1 song in Holland, he stepped back and said, ‘Let him have his shot with it in America’. If he had put his record out, mine might never have made it.”

Rocky’s version reached No.8 in America, No.4 in Canada and No.1 in Australia.

Dreamin’ up hits

The Rick Nelson hits encouraged Johnny and Dorsey to return to recording. When Willie Nelson turned down the folk-pop ballad Tall Oak Tree, Dorsey released it himself and scored a Top 30 hit in 1960.

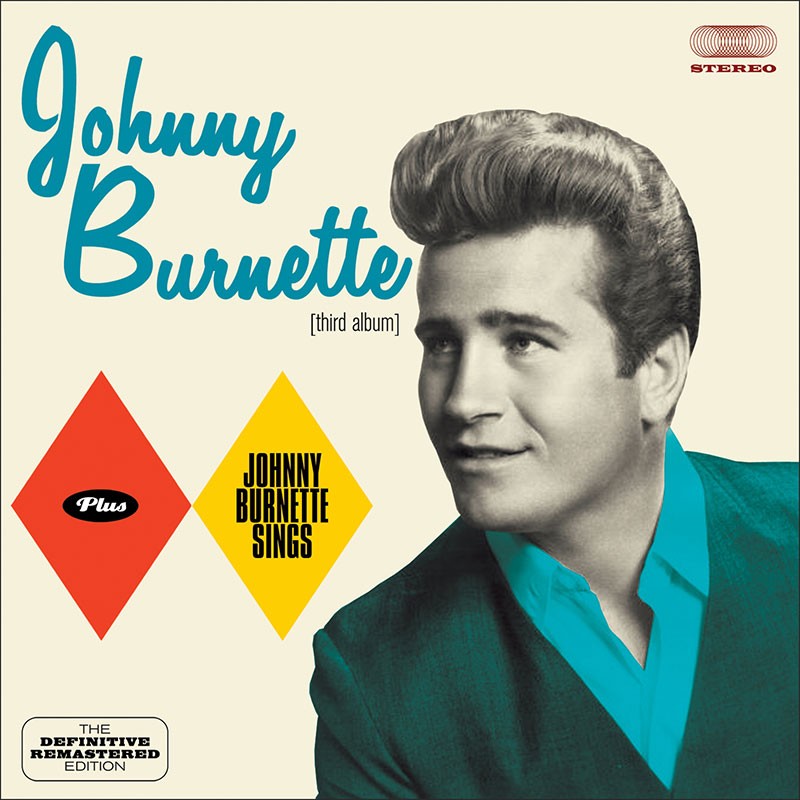

It was Johnny who enjoyed the greatest success, however, when Dreamin’, written by Barry De Vorzon and Ted Ellis, reached No.11 in the US and No.5 in the UK.

The follow-up, You’re Sixteen, penned by the Sherman Brothers, did even better, hitting No.8 in America and No.3 in Britain.

Produced by Snuff Garrett, the catchy, strings-laden singles sounded very different to the raw and aggressive recordings of the Rock ’n Roll Trio, but in their way were just as influential and shaped the sound of American pop prior to the emergence of The Beatles.

“After that, everybody from Bobby Vinton to Dean Martin was using violins the way my dad did,” Rocky boasts. “Everything that was recorded after 1962 sounds just like Dreamin’ and You’re Sixteen.”

Burnette also scored Top 20 hits with Little Boy Sad and God, Country and My Baby. Looking back on his father’s fame, Rocky explains: “We had such a yo-yo existence. We were up and then we were down. When Dreamin’ and You’re Sixteen came out, boy, all of a sudden my dad was getting the TV work he needed. He was doing the international tours. He had his own record company. The first act that he signed to the label was Karen and

Richard Carpenter.”

Tragically, Johnny’s life was cut short at the age of 30 on the evening of 14 August 1964, when a cabin cruiser ran into his unlit fishing boat on Clear Lake, California.

The loss was a profound blow to Dorsey, says Rocky. “They fought, like a lot of brothers do, but they loved each other.

They depended on each other. When my dad died, Dorsey was never the same again.”

Rediscovered once more

At the time of Burnette’s death, the Rock ’n Roll Trio was all but forgotten in America, as was rockabilly itself. On the cusp of the 1970s, Rocky remembers: “We were all standing outside Dorsey’s house when this old jalopy of a Cadillac drove up with a convertible top that had holes in it.

“This kinda chubby guy got out and walked over to us. Dorsey was looking at this guy like, what’s going on here? The

guy looked up at him with tears in his eyes and said, ‘You don’t remember me, do ya, Dorse?’.

“My uncle said, ‘Gene, is that you?’ It was Gene Vincent. He was bloated and unhealthy. He hugged Dorsey and said in his ear, ‘They don’t remember us anymore, Dorse. They don’t care about us anymore’.

“He came in the house and we had a wonderful day telling all the old stories. Just a few months later, Gene passed away. Everybody in my family was upset.”

During the 70s, Dorsey focused on country music and had a string of small but regular hits on the country chart, the biggest being In The Spring (The Roses Always Turn Red) (No.21), Darlin’ (Don’t Come Back) (No.26) and Things I Treasure (No.31).

Dorsey’s songs recorded by other artists include As Long As I Live (Jerry Lee Lewis), Here Comes That Feeling (Brenda Lee) and Sad Boy (Stevie Wonder).

The latter song was about a boy drowning and, released just before Johnny’s death, spookily prescient.

Dorsey also met an early death, from a heart attack on 19 August 1979, aged 46. It was just before the rockabilly revival that brought the Rock ’n Roll Trio acclaim.

“If Dorsey had realised how many fans he had in England, Europe, Australia and Japan, it would have kept him alive another 10 or 15 years,” says Rocky.

As it was, it was only when their own singing careers took off that Rocky and Billy Burnette learned the full scale of their father’s influence.

“Paul McCartney told me he and John Lennon would get up every morning and the first record they’d put on was the Rock ’n Roll Trio, that was their favourite record,” says Billy. “The Beatles did Lonesome Tears In My Eyes and the first song Led Zeppelin rehearsed was Train Kept A-Rollin’.”

“Neil Sedaka gave me a big hug and said, ‘Your dad is one of the biggest stars that ever lived’,” adds Rocky. “Mick Green from Johnny Kidd and the Pirates said, ‘We were sitting in the movie theatres when we saw the Rock ’n roll Trio in Rock, Rock, Rock! and that’s what got us into the music business’. Elvis, when he died, had seven Johnny and Dorsey things on his jukebox at his house.”

The influence of Johnny Burnette and the Rock ’n roll Trio can be heard in every rockabilly band on the scene. Asked where he’d put them in the rockabilly hierarchy, Billy answers, “I would have to say they were No.1.”