Tennessee Ernie Ford was a middle of the road TV showman when he released the album bearing the title of his biggest hit. But many of the early-50s tracks within its grooves actually revealed an underrated album of earthy, groundbreaking boogie. Jack Watkins hauls Sixteen Tons for another spin.

The host of a prime-time NBC variety show which, at its peak, attracted 30 million viewers, his persona mixed sleek-suited sheen with homely, pipe-smoking good humour. Cornball catchphrases like “bless your pea-pickin’ hearts” played on his Tennessee country boy roots. But while he fooled around with his guests in a folksy kind of way, his music had grown increasingly mainstream and safe.

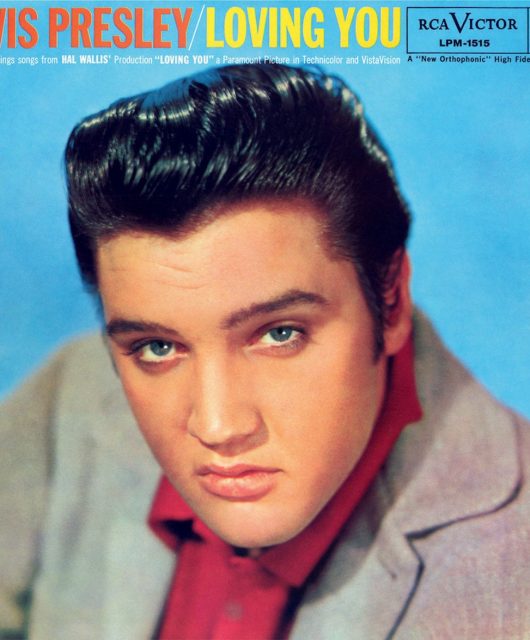

His then-new 1960 album, however, batched together his most celebrated hit with 11 classic other singles, and was a reminder of the earthier material he had delivered in the first years of the 1950s. Crucially, it included several of the ground-breaking country boogies that put him up there with the likes of the Bill Haley & The Saddlemen, The Maddox Brothers and Rose, Cowboy Copas and Moon Mullican, as one of the more revved-up performers in the hillbilly field of the period.

In the beautifully curated Bear Family Records boxed set, Tennessee Ernie Ford: Portrait of an American Singer, music historian Ted Olson asserts that: “In his swaggering performances of mostly self-composed boogie songs, recorded a few years before Sam Phillips’ legendary discoveries in Memphis, Ford was arguably the first rock’n’roller – or at least among the very first wave of musicians – who fused black and white styles and repertoires to forge a revolutionary new sound.”

Such praise is timely, as Tennessee Ernie’s star has faded in recent decades. It’s worth restating that in his heyday he was a major recording artist. Not only did the single of his version of the Merle Travis song Sixteen Tons, released at the end of in 1955, top the American pop charts and sell four million copies, but Ford went on to score a total of 20 Top 10 Country and four Top 10 pop singles in the US. He sold more than 90 million albums globally, and was well-loved in Britain, where Sixteen Tons repeated its top-chart-topping success.

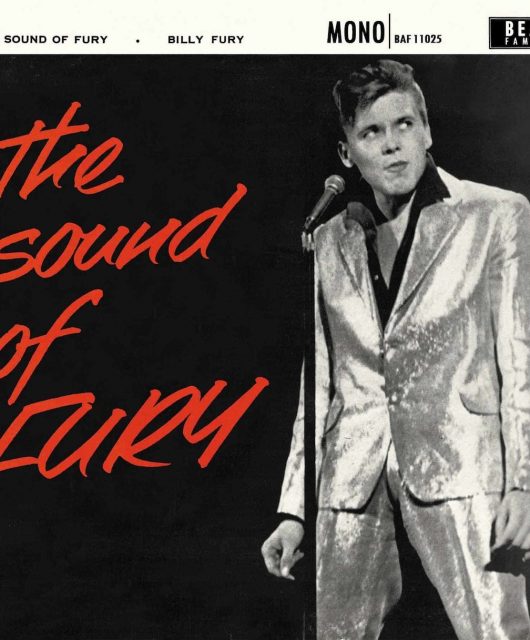

Ford had already been the first country artist to appear at the country’s then most prestigious “showbiz” venue of the London Palladium, in 1953. Many stars of British rock and pop whose formative years came in the 1950s, such as Nick Lowe, Tom Jones and Elton John, recognise Ford’s legacy. Billy Fury even had a hit with a somewhat overwrought version of the Ford ballad Give Me Your Word in 1966.

From Farm to Fame

Tennessee Ernie’s all-round ease as a performer was no surprise. He’d served a long apprenticeship. Born in 1919 in Bristol, Tennessee, in his youth Ford helped out on family farms in the area and loved to hunt and fish, subjects he’d return to in his earliest recordings. He sang in the local Methodist church choir, and played trombone in the school band. By 1937 he was broadcasting on the local Bristol radio station.

Relocating to southern California after the World War II, alongside his continued broadcasting, public performances showcasing his rich and rangy bass-baritone brought him to the attention of Cliffie Stone, bass player, broadcaster and talent scout whose connections with Capitol Records had been instrumental in getting Merle Travis signed to the label. Bringing Ford onto his new Hometown Jamboree TV show, by early 1949 Stone’s contact’s also got Ford on a Capitol contract. Ford’s association with Capitol would last 28 years, long after he’d ceased to be

a major-selling artist.

The earliest track on the Sixteen Tons album, I’ve Got The Milk ’Em In The Morning Blues, came from Ford’s first recording session in January 1949. Written by Ford, it was a country song loaded with rustic good humour. Affectionate references to wall-eyed Jersey cows, and getting “smacked with a tail full of cockle burrs” rang true to the small farm life Ford knew well. The exaggeratedly thick Appalachian accent Ford adopted, a curiosity today, was hardly less so to record buyers at the time in an increasingly urbanized America.

Country Junction, as well as Philadelphia Lawyer, a Woody Guthrie song which was a bigger hit for the Maddox Brothers and Rose, emerged from Ford’s second session a less than month later.

Many of the key personnel on Tennessee Ernie’s early sessions were already on board, including Cliffie Stone on bass, Eddie Kirk and Merle Travis on guitars, Harold Hensley on fiddle, Speedy West on steel guitar, and Billy Liebert, who played the accordion and sometimes the piano. But for this second session they were joined by Moon Mullican, whose energetic and fluid piano style made an important contribution to Country Junction, written by Ford and Stone, and the first of Ford’s country boogies.

If Mullican is mentioned at all these days, it’s usually to cite him as early influence on Jerry Lee Lewis, but he deserves better, thanks to songs like Pipeliner Blues, Cherokee Boogie (Eh-oh-Aleena), Rocket To The Moon, Rheumatism Boogie and I’ll Sail My Ship Alone. His pounding barrelhouse piano and warm vocalising make him a standalone country great in his own right, and Tennessee Ernie would been have grateful to have him along for that Hollywood session in 1949.

Smokey Mountain Boogie represented a further upping of the octane. Evoking the Great Smoky Mountains of Ford’s native Tennessee, it had some rough and ready electric guitar, as well as spicy flavourings from Speedy West, one of the most imaginative and spontaneous exponents of the pedal steel guitar of the era. The song reached No.8 in the country chart, Ford’s biggest hit to date.

- Read more: Classic Album – In Style with The Crickets

- Read more: Classic Album – Matchbox

Ford’s increasing confidence as a singer was reflected in his next two singles, though neither falls into the country boogie category. Mule Train, his first country No.1, also put him in the pop charts for the first time, towards the end of 1949.

Clearly there was a huge appetite among the public for this strange song, given that Frankie Laine had already taken his own version to number one, and a Bing Crosby version was also released around the same time as Ford’s shot was put out by Capitol.

Another Singin’ Cowboy

Pre-rock’n’roll, some of the most imaginative pop material was coming out of the cowboy genre, and Mule Train was up there with the best of them. A fun song to perform, even Gene Autry, the greatest singing cowboy of them all, who seldom stretched far out of gentle crooning mode, gave it one of his most energised performances.

But Ford’s version was a corker, rivalling Frankie Laine’s roaring, galloping bravado. Ford’s delivery of the lyric was more nuanced than Laine’s, Fred Tavares’ steel guitar echoing his falsetto. Stone’s slapped bass and the acoustic guitars of Kirk and Travis provided a rhythmic backdrop.

For Anticipation Blues, another big country hit, Ford revived his earthy, backwoods dialect. With Harold Hensley’s backyard fiddle inflections just perfect, over a sturdy country beat and a jazzed-up refrain, Ford gave an amusing account of the agonies of a young couple awaiting the birth of their baby, his deployment of a hoarse sounding yodel underscoring the air of nervy, madcap panic.

The Terry Gilkyson-penned The Cry Of The Wild Goose, drew another extraordinary vocal performance, with Speedy West’s pedal steel underscoring the eerie mood on a song that defies easy categorisation, being neither outright pop, nor country. Once again it was a big crossover hit for Ford, yet once again he was commercially outperformed by Laine’s more heavy-handed version, which went to No.1.

In the summer of 1950, another fine guitarist, Jimmy Bryant, was a regular on the Ford recording sessions, one of which yielded The Shotgun Boogie, seen by some as the supreme example of a hillbilly boogie. Self-penned, again it placed the singer in a picture-perfect country setting, this time with “big fat rabbits jumpin’ in the grass” and “hickory nuts so big you can see ‘em in the dark,” while Ford tried to squire a local hottie before getting chased off by her father’s shotgun.

The ensemble playing was perfect, Speedy West’s wizadry once more particularly evident. But the big difference from the earlier Ford boogies was the inclusion of drums, played by “Muddy” Berry. Not only did they mark out the back beat, but were also used as to create the shotgun effect.

Blackberry Boogie and Catfish Boogie were two more excellent numbers off the same rootstock as The Shotgun Boogie, doing well for Ford in 1952 and 1953 respectively, the latter as the flip side to another of Ford’s greatest songs – though omitted from the Sixteen Tons album – Kiss Me Big.

Yet the singer would never allow himself to be confined to a single musical form, as the torchy Bright Lights and Blonde Haired Women, another of the welcome variations in pace on the album, and recorded in 1950, indicates.

Sixteen Tons itself was another of Ford’s songs that didn’t really fall into any easily definable genre, even though it became a massive commercial hit, for once Ford’s version outscoring that of Frankie Laine. Merle Travis had written the song in 1946, but his acoustic version which had been included on his album Folk Songs Of The Hills a year later, made little impact at the time.

But, given a gentle rocking beat a decade later, with Ford infectiously snapping his fingers – an effect arrived at accidentally as he tried to mark out tempo during the recording session – the song dominated both the pop and country charts, topping them both for eight and 10 weeks respectively in early 1956.

Yet the song’s political nature, related to the lot of a coalminer, initially had made Capitol reluctant to even release the song. In 2015, the Library of Congress announced that Ford’s recording of the song was to be inducted into its National Recording Registry, a status granted to few.

But Ford, a likeable man who had never let fame go to his head and who struggled all his life to adjust to it, had long before admitted to being astonished at its success. “Don’t think that I’m blasé about it. Every time I think about it, I have to hold my head. It terrifies me.”