At the time of The Blues Brothers’ cinema release in 1980, soul and R&B weren’t exactly the most in-vogue genres in America. But they were to have a renaissance in the wake of Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi’s heartfelt love letter to the joys of Black music…

At the time The Blues Brothers arrived in cinemas in the summer of 1980, soul and R&B were both seen as antiquated musical genres, certainly as far as the charts were concerned. Paul McCartney’s electronically-driven Coming Up was No.1 on the Billboard. Lipps Inc’s disco-funk novelty record Funkytown at No.2. The soul and blues stars that The Blues Brothers shone a spotlight on, for the most part, hadn’t had a hit in years.

Those giants of Black music – Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, James Brown and Cab Calloway among them – were seen as so passe that Universal, the studio behind the film, actually lobbied its director John Landis to cast more contemporary stars instead. In the end, Landis and the film’s co-star and co-writer Dan Aykroyd – himself a massive fan of retro soul and R&B – won out and can certainly be credited with helping revive the commercial fortunes of some of 60s music’s biggest names.

Going Live

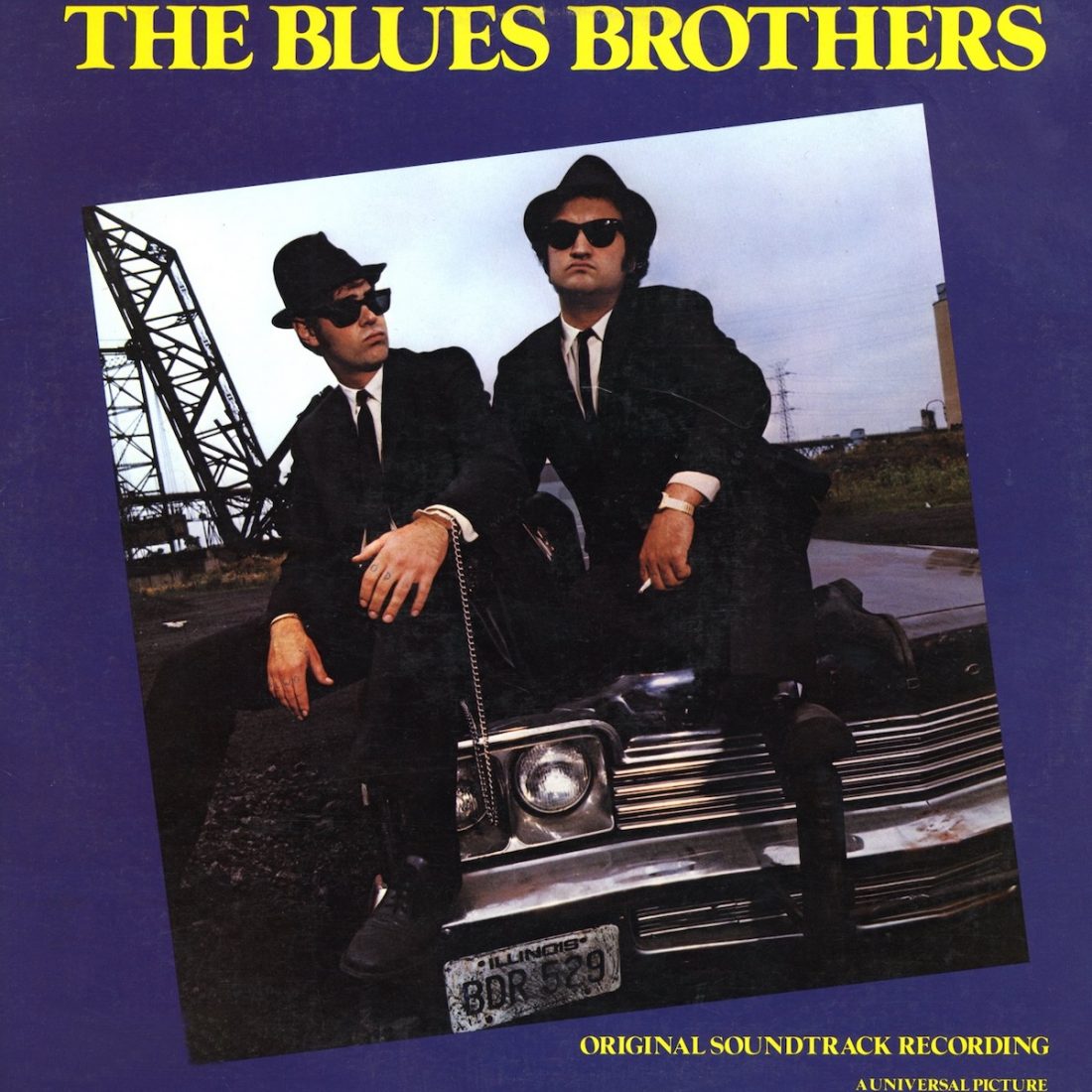

But then blues and soul were already baked into the concept of The Blues Brothers. Before the story of Jake and Elwood Blues became a movie, they were the stars of one of the most popular TV shows on American TV. Created by Dan Akyroyd with his friend, John Belushi, they’d originally been formed as an opening act for comedian Steve Martin. Clad in jet-black suits, with ever-present shades, they would – with the help of an all-star band – belt out a series of R&B and soul covers with Belushi bellowing into the mic and Aykroyd dancing as if stomping on an army of ants.

Debuting on Saturday Night Live in 1978, they became one of the comedy show’s signature acts, so much so that Akyroyd and Belushi put out an LP, Briefcase Full Of Blues, in the November of that year, which peaked at No.1 on the Billboard Album Chart (its first two singles – covers of The Chips’ Rubber Biscuit and Sam & Dave’s Soul Man – both went Top 40). With the success of the album and their popularity on SNL, it was only a matter of time before the brothers Blues graduated to the big screen. The only question was, who was going to make it?

The bidding war for what would become the Blues Brothers movie was intense. In the end, it was Universal who won the rights to tell Jake and Elwood’s story on the big screen. But little could they have known quite how chaotic the shoot would be for their prized acquisition. For one thing, Dan Aykroyd had not only never written a screenplay before, he’d never even seen one. So when the script came through for what would be his first movie as writer it was a whopping 324 pages, three times longer than a standard screenplay.

“The script is never-ending,” then-Universal Pictures president Ned Tanen told his colleagues (as quoted in Vanity Fair). “It doesn’t really work. It’s like a long treatment or something.”

Shake It Up Baby

But whatever – Universal were hungry for The Blues Brothers, not just because of the popularity of the two suited-up lead characters, but because of one of its stars – John Belushi. The 5ft 8in fireball had been the breakout star of 1978’s highest-grossing comedy, National Lampoon’s Animal House, and Universal, who’d made the film, wanted more of that Belushi magic.

So they hired Animal House’s director John Landis to get Aykroyd’s unwieldy script into shape. The story was a simple one – Elwood (Aykroyd) is there to greet his brother Jake (Belushi) from prison, and, after being told the Catholic orphanage where they were raised will be closed unless it pays $5,000 in property taxes, set about reforming their band, the Blues Brothers, to help raise the money – “we’re on a mission from God.”

Which rather makes The Blues Brothers sound like a basic, small-scale comedy, made on a modest budget. But Aykroyd and Landis’ plans for The Blues Brothers were epic. It may have had a straightforward storyline, but it would be punctuated by elaborate action sequences and lavishly-staged musical numbers. This would be a big-screen comedy like no other.

Sweet Home Chicago

But as filming got underway in Chicago, it soon became clear that Landis had bitten off rather more than he could chew. The movie found itself behind schedule almost immediately, due in no small part to Belushi’s penchant for hard partying. A frequent visitor to some of the city’s buzziest joints, such as Wrigley Field and the Old Town Ale House, Belushi was used to staying up all night, fuelled by cocaine and alcohol.

Filming days then were often spoiled by Belushi being unable to perform, or simply not turning up. In fact, the set of The Blues Brothers was almost caked in cocaine. Akyroyd too was a frequent user (though nowhere near as much of a coke-hound as his uncontrollable co-star), as was Carrie Fisher, who’d been cast in the film as Jake’s uber-vengeful ex-fiancée. According to Fisher – who was Aykroyd’s girlfriend at the time – most of the staff behind the bar of the cast’s private hang-out, the Blues Club, doubled as dealers.

“Cocaine was a currency,” Aykroyd recounted to The Guardian in 2020. “For some of the crew working nights, it was almost like coffee. We drove John Landis crazy. Sometimes he didn’t know whether we were going to show up for work after the parties.”

But of course, as much as the budget-breaking stunts and Belushi’s winning turn as the loveably out-of-control Jake would help define The Blues Brothers, it’s the music that really binds the movie together. And it’s important to remember that it wasn’t just R&B and soul that were out of fashion in 1979/80, it was musicals themselves. Just witness the performance of Shake A Tail Feather, in which Ray Charles performs the Five Du-Tones song intercut with a crowd of extras in a poverty-stricken Chicago ghetto dancing like it’s a Busby Berkeley musical number. Then there’s Aretha Franklin’s Think, set in a Chicago diner, but performed with the vigour and scale of any 60s musical. But while musicals before this painted their worlds in primary colours, The Blues Brothers was an altogether grittier kind of project – Stanley Donen by way of Hal Ashby.

Stars Align

“In 1979 the big acts were ABBA and the Bee Gees,” Landis says in the book Wild And Crazy Guys. “Ray Charles was doing well – he was doing country and western at the time –but rhythm and blues was totally out of fashion. That was one of the reasons why we were able to get everyone with a phone call. It was a unique situation where Danny and John used their celebrity to focus attention on these brilliant artists.”

Aside from Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin, the musicians invited to appear in The Blues Brothers included such soul and blues greats as James Brown (who performs The Old Landmark), John Lee Hooker (Boom Boom) and Cab Calloway (Minnie The Moocher), while even the Blues Brothers band themselves were big names in their own right – among them Steve Cropper and Donald Dunn who were members of Booker T And The MG’s, while horn players Lou Marini, Tom Malone, and Alan Rubin had all played in jazz-rock outfit Blood, Sweat & Tears and were the house band on Saturday Night Live. Drummer Willie Hall had been a member of funk group The Bar-Kays and had also played with Isaac Hayes. Matt ‘Guitar’ Murphy, meanwhile, was a veteran blues axeman who’d played with Howlin’ Wolf and Memphis Slim.

At the same time as Landis was having trouble with Belushi, he also found filming the musical numbers increasingly stressful. Watch Franklin’s performance of Think, and the lip-syncing is completely out, so hard did she find it, while James Brown‘s performances were so wildly different each time that Landis ended up recording the singer’s vocal live on set, with the music pre-recorded and played over the top.

Made Of Money

It was the film’s action sequences, however, that really pushed The Blues Brothers’ budget to its limits. Landis filled the movie’s final chase scene, which travels through Chicago and ends at the Cook County Assessor’s office, with two helicopters, four tanks, a real SWAT team and 200 Chicago police officers. Nothing on The Blues Brothers was small scale.

Initially budgeted at $17.5 million, the eventual cost of The Blues Brothers would balloon to $27.5 million, making it at the time, one of the most expensive comedies ever made. And Universal had even cooled on its commercial prospects. By this time, both Aykroyd and Belushi had left Saturday Night Live, reducing their visibility, while Belushi’s fame had taken a hit after the failure of Steven Spielberg’s big-budget action comedy 1941. Yet when The Blues Brothers opened on 20 June 1980, it raked in $4,858,152, ranking second for that week after The Empire Strikes Back.

Critics may have been dubious as to its charms – “There is no more material sustaining The Blues Brothers than one would find in a silent comedy short running 10 or 20 minutes,” moaned The Washington Post. “While Landis must take the rap for the overscaled production and the slovenly workmanship, Universal has only itself to blame for authorising a princely budget for a scrap of comic content” – but audiences were lapping it up.

It’s rare for a comedy movie to have such a lasting legacy as The Blues Brothers. It’s been endlessly imitated and copied – there are numerous Blues Brothers tribute shows across the globe and even those who have never seen the film recognise those iconic black suits and shades. And the movie’s success gave a second lease of life for many of its Black performers, reminding audiences why they’d fallen in love with that music in the first place.

“The Blues Brothers is a testament to John and Dan’s passion for the blues,” Landis told The Guardian. “They took advantage of their celebrity to focus attention on soul music. On the level of Dan wanting to proselytise about this music, it was an enormous success. It brought everybody involved with it back with a vengeance.”

Subscribe to Vintage Rock here