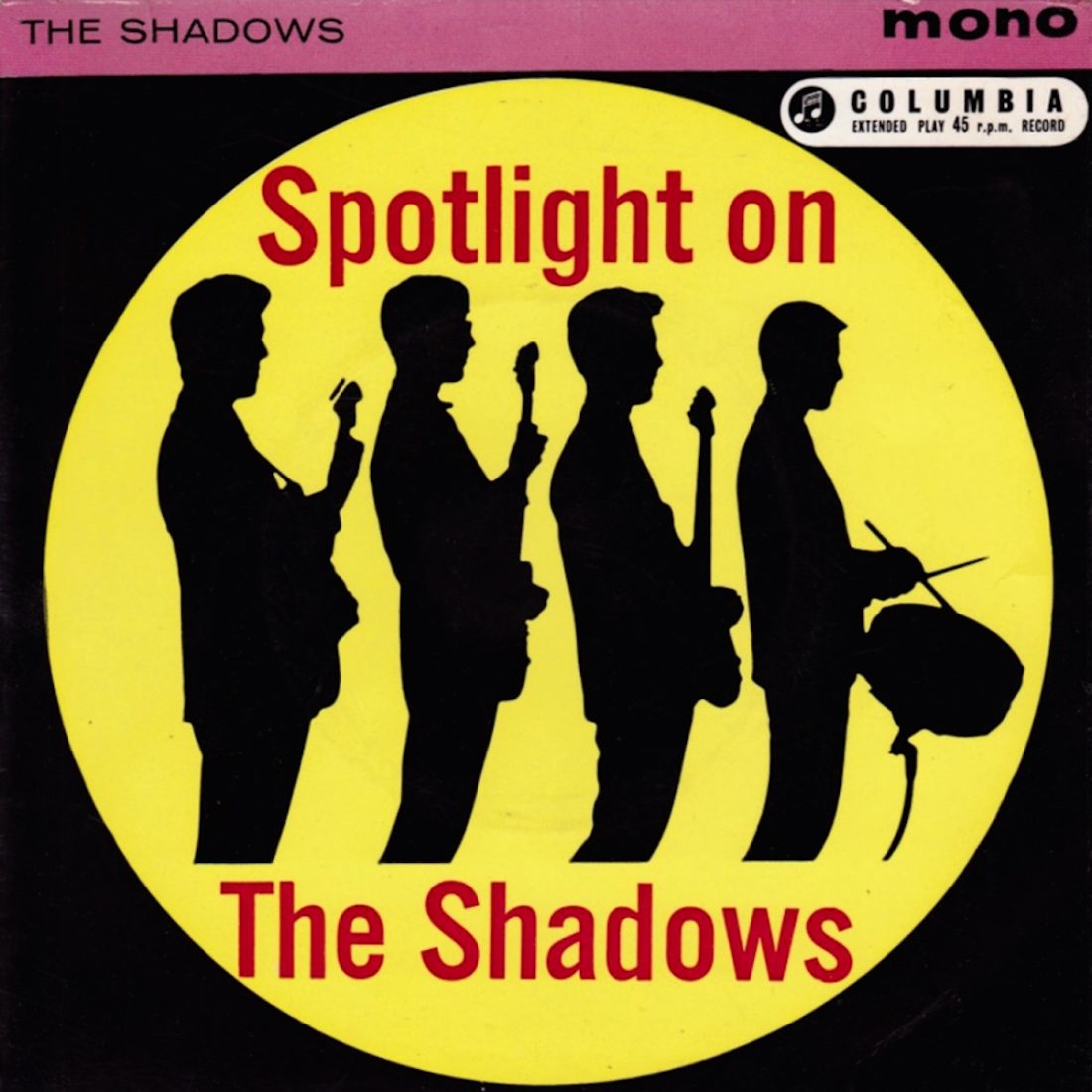

In 1960 The Shadows revolutionised British rock’n’roll with the electrifying riff of Apache. Vintage Rock catches up with Bruce Welch and Brian Bennett to explore why The Shadows’ timeless music still resonates with fans and continues to inspire artists

With 69 UK singles chart entries to their name, The Shadows took the six-string instrumental into the mainstream with huge hits such as Kon-Tiki, Wonderful Land, Foot Tapper, and Dance On!. However, it is for Apache, the atmospheric earworm released in July 1960, that they will be likely be most fondly remembered.

It could be argued that no other British rock outfit has had such a profound influence on subsequent generations of UK music makers than The Shadows. Hyperbolic perhaps, given that three years after their hit Apache, The Beatles duly came along with Please Please Me and changed the cultural landscape forever. But would such a monumental occurrence have taken place had Hank Marvin, Bruce Welch, Jet Harris and Tony Meehan, not stepped out from Cliff Richard’s shadow (pun intended) to establish themselves as a leading light in UK rock’n’roll?

Vintage Rock was thrilled to spend a couple of hours in the company of founding member Bruce Welch and powerhouse drummer Brian Bennett to reminisce, as well as sharing time with musician and author / Shadows super-fan Bob Stanley, to celebrate the band’s golden legacy.

“Good morning!” exclaims a buoyant Bruce Welch as he warmly welcomes us on a glorious spring day. “The sun is shining and I’m raring to go!” Vintage Rock would soon be transported back to an imagined monochrome Newcastle, as the celebrated guitarist recounts the incredible origin story of the mighty Shads…

Teenage Kicks

“Hank and I went to school together in Newcastle,” opens Bruce. “When we were growing up, it was all big band music. Every big city had a ballroom and people would go and dance to an orchestra fronted by crooners. But rock’n’roll came along and it just wiped all that out.

“God knows how, but Hank and I both passed our 11-plus exam and soon bonded over our shared love for this new music. We were 14 in 1956, the year both Lonnie Donegan and Elvis happened, and we started hearing all these incredible US artists like Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and Fats Domino. The following year, along came The Everly Brothers and, of course, the biggest influence for us – Buddy Holly And The Crickets with That’ll Be The Day.

“We’d read the music papers to find out about the stars of the day and Lonnie said, ‘Anybody can do this skiffle music, all you need is two or three guitars, a washboard and a bass’. I, like everyone else, immediately went out and got my first guitar – a cheap thing bought from a sports shop.

“Lonnie was the catalyst because everyone formed skiffle groups. Hank and I had a skiffle group in Newcastle, The Hollies had a skiffle group in Manchester and, as everybody knows, John and Paul had a skiffle group in Liverpool… and they went on to do quite well. But Lonnie was the king… My group was called The Railroaders and, by the age of 16 when we left school, Hank had joined us.”

A Capital Idea

Meanwhile, 280 miles south in North London, a young teenage drummer was making a name for himself. “I was a jazzer,” shares Brian Bennett, “and Shelly Manne was my hero. I was also in a skiffle band called the London Skifflers. Skiffle was great because it provided people who didn’t have a lot of money with the opportunity to make some noise.

“Rock’n’roll first piqued my interest when Blackboard Jungle, featuring Rock Around The Clock, was released. Bill Haley was one of the early influences on everybody really. I would frequent this small basement located downstairs at The 2i’s coffee bar in Old Compton Street. Everybody would congregate down there to play this new music. The room only held about 100 people, but it really was the birthplace of British rock’n’roll. I did a couple of sessions down there and was asked if I would like to be the house drummer playing alongside Tony Sheridan and Brian ‘Licorice’ Locking.”

Back in Newcastle, the lure of London’s bright lights proved too intoxicating when The Railroaders headed south to enter a national skiffle competition before embarking on a life-changing adventure for Hank and Bruce…

London Calling

“We travelled down from Newcastle for the competition in April 1958,” recalls Welch. “After we had finished third in the contest, the other two guys in the group said they were heading home. But Hank and I just looked at each other and said, ‘We think we’ll stay’. Now, I can’t tell you what a decision that was: two 16-year-old Geordie kids, alone in London with nowhere to stay.

“Luckily for us, the manager of the theatre where the competition had taken place phoned a landlady that he knew, who just happened to be Geordie, and she took us in. We lived in her attic for six months – rent free!

“From the beginning of April to September 1958, we went to The 2i’s every day, because it was the hub of excitement and was where Tommy Steele had been discovered. We would meet people there that would become huge in our lives – Jet Harris, Tony Meehan, Brian Bennett – but we didn’t know it at the time.

“Jet was already considered a proper musician and legend. He was 18 and the first guy to own an electric bass guitar in this country. He was an incredible player and we would jam together down at The 2i’s on this tiny, 4ft wide by 12ft long stage. One time there was a guy standing in front of us, wearing a sort of Peaky Blinders cap, who asked if he could join us on drums… that was Tony Meehan and he was 15. We didn’t realise it, but that would be the first time ‘The Shadows’ played together.”

Espresso Yourself

“Tony was a great drummer,” offers Bennett. “When he first came down to 2i’s, he was very young. Hank and Bruce were just these couple of Geordie guys who would hang around, but they remembered that they’d seen me play a cover of Peggy Sue at the Regal Edmonton with a group called Errol Hollis And The Velvets – they were amazed that a bloke like me could replicate Jerry Allison’s paradiddle playing.

“But that was the 2i’s, it really was a melting pot. Cliff Richard popped in a couple of times, Vince Taylor went down there and used our band, which became known as the Playboys for a short time. We just loved the music and none of us were particularly interested or aware of success at the time. There was never any sense of animosity. We were all in it together and helped each other. We just loved being part of this new music.

“Jack Goode would scout for talent for his Oh Boy! TV show, and booked Licorice, Tony Sheridan and me as a sort of resident small band to play opposite Lord Rockingham’s XI. So, we ended up backing people like Conway Twitty, Brenda Lee and a lot of the other US acts that came over.”

Another influential person snooping the joint for talent was the Teddy Boy-turned-entrepreneur, John Foster. “Johnny came down to the 2i’s after he’d heard about a great guitarist,” remembers Bruce. “He said, ‘I’m Cliff Richard’s manager and I’ve got a three-week tour booked’. We didn’t really know who Cliff Richard was, but Hank played Johnny all the great guitar licks of the day, and he immediately offered Hank the gig. Hank replied, ‘That’s great, but I’ll only do it if my mate, who is a really good rhythm guitar player, can come along, too’. So, Johnny said, ‘Okay, let’s go and meet Cliff’.”

King Of British Rock’n’Roll

“We went round to a tailor’s shop on Dean Street where Cliff was having his famous pink jacket fitted,” continues Bruce. “He asked if we would mind going to his house to have a play. So, we went out to the council house in Cheshunt where he lived with his mum, dad and three sisters. In the front room we played him every song we knew for about three hours and Cliff said, ‘Great, let’s do it’. I thought he looked like Elvis. He had the Elvis haircut, sideburns, and had that olive-looking skin. He looked like a star.”

“We then hit the road and were the fifth band on the bill. That three-week offer lasted for the next 50 years. Initially we were called The Drifters and featured two of Cliff’s mates from Hertfordshire. But the drummer and bassist, Ian Samwell, who had written Move It, decided to leave and we suggested two guys we’d met down at The 2i’s – Tony and Jet.”

“Every night we’d watch Cliff work those full houses and it was incredible, remembers Bruce He only had to wiggle his legs and a riot would break out. As far as Cliff was concerned it was the five of us… five mates doing what we do. There was never any feeling from Cliff that we was just his backing group. In fact, Cliff kept telling his producer, Norrie Paramor, to check us out. After we auditioned for Norrie in his West End office he offered us the opportunity to make two records as the Drifters in 1959, but both discs flopped.

“We didn’t know there was a huge US Black vocal group, who were No.1 at the time, called The Drifters and they took out an injunction preventing us from using the name in the States. Hank and Jet then went to a local pub to think up a new group name. It was Jet who pointed out that we were always, quite literally, in the shadows behind Cliff’s spotlight. So that’s where the name came from.”

Strat Attack

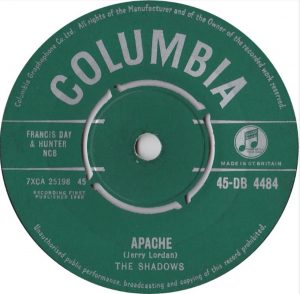

“The first time we used The Shadows name was on a record called Saturday Dance in the summer of 1959,” says Welch, “and suddenly we had three flops on our hands – a year had gone by and we hadn’t had a single hit without Cliff. Between dates on tour a singer-songwriter performing in the show called Jerry Lordan, who was travelling on the same coach, asked if he could play something which he thought might do well as our next single. He grabbed his ukulele and started playing, ‘Daaah-da-da, da-da-da’… it was Apache.

“Our collective jaws dropped and we said, ‘Ooh we like that!’ We took it to Norrie, but he’d already decided we were going to record and release Quatermasster’s Stores, but we were convinced there was something about Apache that was really special. Cliff had already imported the Fender Stratocaster for Hank in May 1959, because he wanted his lead guitarist to sound American – like Ricky Nelson’s guitar player – and we wanted whatever Buddy Holly played. We did a TV show with Joe Brown, who had been fiddling with this Italian Meazzi echo chamber box but couldn’t get on with it, so Hank had a go and loved it. In the studio, when Hank combined the two, Apache came to life and sounded really fresh and new. Possibly, if it hadn’t been for Joe Brown being such a purist, we would never have created The Shadows’ signature sound.

“We tried to badger Norrie into picking Apache as the A-side. He said he’d take both tracks home and play them to his daughters to see what they thought. Luckily, the daughters chose Apache and the rest is history. We knocked off our Please Don’t Tease with Cliff from the top spot and registered our first No.1 in the summer of 1960. Apache spent five consecutive weeks at the top and sold a million records. We became, for want of a better word, ‘famous’, in our own right. Back then, if you had a No.1 hit record, you could top the bill on a tour. It became a whole different ballgame. Cliff was a huge star, of course, but we still chose to work together, so we couldn’t really fail. Touring with Cliff, The Shadows would close the first half of the show and then, after the interval, it would be Cliff And The Shadows. It was a winning combination.”

Somethin’ Else

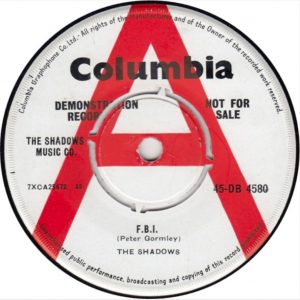

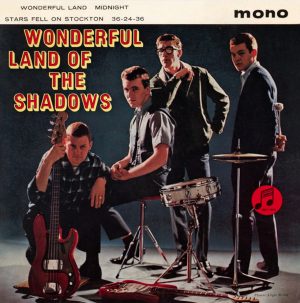

That winning combination continued as hit after hit landed inside the UK Top 10 – Man Of Mystery/The Stranger (No.5), F.B.I. (No.6), The Frightened City (No.3) and The Savage (No.10). Two of them – Kon-Tiki and Wonderful Land – both reached No.1.

Spending eight weeks at the top spot, the Lordan-penned track Wonderful Land would, however, be the last to feature Jet and Tony, with Licorice picking up bass duties and Brian taking up residence on the drummer’s seat.

He said: “I’d been with Marty Wilde for two years and had played in Eddie Cochran’s touring band during his fateful visit in 1960. We weren’t there for that final show at the Bristol Hippodrome because Marty was performing at the London Palladium and a dep band had stepped in. We couldn’t believe it when we heard that Eddie had died on the way back to the airport, as we were due to pick him up again later in the year. Eddie and Gene Vincent were great characters, and they both liked us. Being shown by Eddie exactly how he wanted his songs to be played was a great joy. It was so tragic.

“I was a quite well-known drummer at the time. When Tony left The Shadows they needed someone the next day. I was going into a show in London called Stop The World – I Want To Get Off with Tony Newley where I would be paid £25 a week. Bruce phoned my home and asked what I was getting, after I told him he immediately said, ‘Double it’. Well, it was all over in a second, £50 a week in 1961 was a fortune. I was picked up by Peter Gormley, who was the manager at the time, and we drove to Blackpool where I appeared onstage that night.

“When I joined The Shadows I didn’t think, ‘Right, that’s my career at its top now’. This is not me being big-time you understand, it was just another stepping stone towards being a great player. It was a great job, but I didn’t expect it to last as long as it did because there weren’t many bands that lasted more than two to five years.”

“Brian’s the new boy and he’s been with us for 64 years,” laughs Bruce. “But we really didn’t have any expectations on how long it would last. We were just thrilled to be working with Norrie and Cliff. It was a whirlwind and like Christmas every day throughout the 1960s.”

It’s A Wonderful Life

While Top 10 hits such as Guitar Tango, Atlantis and Shindig, plus No.1s Dance On! and Foot Tapper, all helped cement the band at the summit of the charts, Cliff had already become Britain’s most bankable star. Big screen appearances for The Shadows also beckoned, with the band appearing alongside the singer in films such as The Young Ones, Summer Holiday, Wonderful Life, as well as Finders Keepers.

“Well, obviously we weren’t movie stars,” chuckles Welch, “we couldn’t act to save your mother-in-law. The directors had no idea what to do with us, so they’d just put us in nightclub situations. While Cliff was off shooting his scenes, we’d end up spending a lot of time in dressing rooms or checking out local sights. We’d occupy our time working on songs, I remember writing Bachelor Boy while sitting on a beach in Athens.”

“Making the films was quite interesting,” adds Brian, “especially pictures like Finders Keepers, where we wrote the whole score. “I found being on set at Pinewood Studios fascinating. I’d always been curious about writing music for film, so being around actors at Pinewood and Elstree was incredibly exciting.

“Norrie Paramor was a great mentor for me because he saw my potential as an arranger. We became quite good friends and he was very important to my career. Working with him was a great learning curve.”

Norrie’s influence also aided Bruce’s side career producing records for Olivia Newton-John and Cliff. He said: “I guess, without knowing it at the time, watching Norrie always influenced or intrigued me. You learn from everybody, don’t you? Watching Norrie work was invaluable.”

Keeping Things Fresh

So, did Bennett and Welch enjoy studio time more than being onstage playing concerts? “I enjoyed both, they’re both great disciplines,” states Brian. “To arrange and work in the studio, you need to be at the top of your game. You can’t just walk into a studio and start conducting, so I enjoyed that side. But, playing live is always good because you get that buzz back from the audience.

“I never tired of playing hits like Apache live. It was a great piece of music and I followed the way Tony Meehan played it faithfully. Tony was a very inventive drummer. Over the years I would drop a few things in now and again, but if you changed anything onstage, I’d get a look from Bruce like, ‘What the f*ck was that?’

“I had my Little ‘B’ drum solo that kept things interesting. If I didn’t have that, I would’ve got bored playing Apache every morning, noon and night.”

And what about Bruce? “No, I never tired of playing Apache live either,” he asserts. “But after those first 10 years I decided to step away from The Shadows in December 1968. I thought we’d done absolutely everything we could have possibly done. We had 18 months off, and then Hank and I started Marvin, Welch & Farrar with John Farrar from Australia.

“We didn’t want to do The Shadows at the time, but as soon as we went onstage people would yell ‘Play Apache Hank! Play F.B.I.… Play Foot Tapper…’ We couldn’t escape being The Shadows.”

Shad All Over

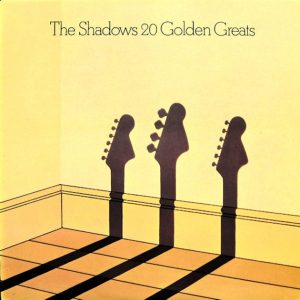

In 1975, the BBC Head of Light Entertainment, Bill Cotton, approached The Shadows to represent the UK at that year’s Eurovision Song Contest. “While I fluffed a couple of lines, we still came second,” admits Bruce. “The Shadows were back in the charts with our Eurovision entry, Let Me Be The One,and suddenly there was a clamour for us to do concerts. Shadowmania was back again and EMI wanted to cash in.

“The label wanted to put out all our hits on a compilation album, complete with a television advertising campaign. We had our reservations, but they released 20 Golden Greats and f*ck me it sold well over a million albums – so we went back to work.”

Capitalising on the renewed interest, cover versions of Don’t Cry For Me Argentina, released in 1978, and the following year’s Theme From The Deer Hunter (Cavatina), returned the group to the Top 10, but did everything feel different for Welch?

“Absolutely it did,” he replies earnestly. “People would ask why we were doing covers of this and that. But we’d sell hundreds of thousands of these records and the fans were always there and supported us throughout.”

Fan-omenonal Following

And the loyalty of Shadows fans is one thing Vintage Rock would never question. “While Cliff was the sex symbol and had all the women fans, we had all the guys wanting to play guitar like Hank,” continues Welch. “We have incredibly loyal followers, still twanging away at conventions and it’s so nice when we get to meet them.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Bennett: “The fans are the best you could wish for. We’ve never been a big-time band and we will always take the time to talk with them because our fans have become our friends. We wouldn’t be where we are today without them.”

“I don’t wish to sound flash,” adds Bruce, “but I know that if we got together again the fans would be right there with us and we’d sell out everywhere. I do miss it, but we won’t do it again, not now.”

That’s A Rap

While that declaration appears to draw a line under any future Shads reunion tour, there’s plenty on the horizon to excite fans, not least a new Hank Marvin documentary. While Brian has a musical project that’s in the pipeline and his much-anticipated autobiography is also on the way.

“I’ve written a musical, which is called Once Upon A Time In Soho – or just Soho – which is about the West End in the 1950s,” reveals Bennett. “It’s coming together very nicely, with plans for it to be made into both a movie and a stage play. Featuring brand new songs, it’s a proper musical and we start shooting the film in April-May of this year. I can’t tell you who has signed up to appear at the moment, but they’re all great people. The book is more or less finished. My kids are reading it to make sure I haven’t got anything wrong, and I’ve written it with Lesley-Ann Jones, who’s a great writer and a good friend.”

Bennett’s book promises to be a fascinating read. His solo work has been just as influential as The Shads, with hip-hop connoisseurs and sample nuts hailing him as a genius. What does Brian make of it all? “Initially I wasn’t aware because I didn’t listen to rap music,” he confesses. “But I heard a piece of music being played and thought that’s one of mine!

“They hadn’t just sampled the snare drum but the whole groove. I was playing golf with a producer called Steve Jenkins and said, ‘Some a***hole – Biz, Boz, Baz – has nicked my stuff’. Steve said, ‘It wasn’t Nas, was it? He sells sh*tloads of records!’”

Nas’ use of Solstice from Brian’s 1978 LP Voyage (A Journey Into Discoid Funk) on Find Ya Wealth is far from isolated. Kanye West also revisited the piece on his 2010 track Lord Lord Lord… “I suddenly became hip,” laughs Brian. “It’s incredible really, isn’t it?”

Dance One!

In a flurry of yet more Shadows-related activity, author and founding member of the group Saint Etienne, Bob Stanley, is also penning a biography on the band.

“The book is out next year,” says the lifelong Shads fan. “I wish I knew what it was going to be called. I thought about calling it ‘What We Did In The Shadows’ but I thought it would be too niche [laughs]. I just want to emphasise their significance and the fact that they were the first British pop group of any real consequence.

“They were the only show in town before The Beatles, really. Everybody wanted to be The Shadows – we had all these British instrumental groups like the Fentones and the Dakotas mimicking them – dressing like them and playing like them.

“I managed to talk with Jet Harris and Tony Meehan while they were still alive and the rest of the guys as well, even Cliff, so it’s all of them, which is wonderful.

“I never got to speak to Licorice Locking and John Rostill, but I’ve got great memories from everyone. They weren’t shy about sharing stories. Sadly, with eachpassing generation, their legacy becomes more fragile. I am definitely going to try to do my bit to make sure their name stays in the history books.”

Something Special

The Shadows were climbing the charts via Genie With The Light Brown Lamp when Stanley was born in December 1964. He’s since become something of a leading authority on the band. “My parents had a Columbia red label demo of F.B.I.,” he recalls. “I don’t know where they got it, but through my toddler’s eyes, it looked special with the big red A. I was too little to read, but I loved the sound. It felt important and really captured me, even though I had no idea what F.B.I. meant. The B-side, Midnight, was a beautiful sleepwalking instrumental and I absolutely loved both tracks.

“I heard Apache and the other hits when 20 Golden Greats came out when I was about 12. It never seemed uncool to say you liked The Shadows. I’ve always loved instrumentals and film soundtracks – I prize melody above anything else on a record – so The Shads are pretty fundamental to the way that my taste developed.

“They’d been there all my life, so seeing them live for the first time on their last solo tour in Bristol and Hammersmith was really exciting.” Does Bob have a favourite track? “Oh, Wonderful Land,” he replies immediately. “It’s so evocative. I know it was written with America in mind, but to me, it’s got that incredible post-war British optimism mixed with a kind of melancholy. It is a tear-jerkingly peaceful piece of music.”

Firm Foundation For Everything That Followed

Is there anything that surprised Bob while writing and researching his book? “Once you get past the very beginning, when they looked a bit moodier with Jet Harris in the band, they always projected this very sunny image,” considers Stanley. “But behind the scenes it was often quite chaotic with people falling out and threatening to leave… perhaps a lot more than you’d expect.

“But ultimately, I think you could say it’s possible that the four-piece British rock group might never have happened without them. I think Hank was just ahead of everybody else in the country when it came to guitar tone and experimentation. Bruce is an incredibly accurate guitarist – he plays fast but is absolutely bang on the rhythm. Tony Meehan and Brian Bennett are both great jazz drummers and the cream of the crop. Combine that with Norrie Paramor as producer and everything was a very tight set-up right from the beginning and Apache. Take The Shadows out of the picture and everything becomes very unstable. They’re the absolute foundation of it all.”

“Yes, we had the normal dressing room arguments that every band has,” says Brian, “but we’ve always respected each other’s playing and talents. We have also remained really good friends. These days Bruce and I will often meet and have lunch together.”

“I’m very proud of what we all achieved and it was great fun,” beams Bruce. “I guess somebody did something right at some stage!”

Vintage Rock would like to express its sincere thanks to Cliff Richard and The Shadows specialists Leo’s Den for their help. For further information click here

Read More: Classic Album – Cliff Richard And The Drifters