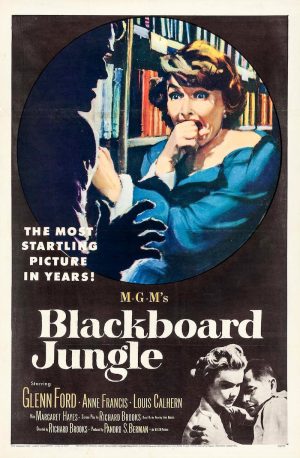

Blackboard Jungle, with Bill Haley’s radical Rock Around The Clock soundtracking the opening credits, was a groundbreaking 1955 film that exposed the tensions of inner-city education, youth rebellion, and social change… But has time dulled the impact of this once-incendiary movie? Hell, no…

It begins with a warning. “Today, we are concerned with juvenile delinquency, its causes and its effects,” the title card states. “We are especially concerned when this delinquency boils over into our schools.”

“The scenes depicted here are fictional,” it goes on. “However, we believe public awareness is a first step toward a remedy for any problem. It is in this spirit that Blackboard Jungle was produced.” And with that, Bill Haley And His Comets’ Rock Around The Clock kicks in, beginning one of the 50s’ most controversial movies, a fiery exploration of disaffected youth at the beginning of the rock’n’roll explosion.

You’d think that viewing Blackboard Jungle now, 70 years on, that time would have dulled its depiction of teen insurrection, that it might look somehow quaint and naive. But for a movie of its vintage, its scenes of violence, from the attempted sexual assault of a female teacher to the brutal beating up of the film’s central character – are still shocking.

Teen Unrest

Nobody could have accused director Richard Brooks of sanitising this domestic threat, though plenty charged him with exploiting it. But while many of Blackboard Jungle’s imitators (and there have been many) are happy to paint their teenage tearaways as one-dimensional rabble-rousers, figures to be feared and loathed, without ever really exploring what has made them the way they are, Brooks’ film is interested in answers.

“These kids were five and six years old in the last war,” a police detective tells the movie’s lead, the former Naval officer turned school teacher Richard Dadier. “Father in the army, mother in the defence plant; no home life, no church life. Gang leaders have taken the place of parents.”

If the movie has a social conscience, so did the book it was based on, boasting a verisimilitude missing from other novels detailing the growing generation gap. Writer Evan Hunter had been a teacher in an inner-city school himself, telling The New Yorker in 2000: “I couldn’t stand it. I’d go in and give them everything I had. I would use all my acting talents, all my creative talents, trying to make interesting assignments for them. They weren’t buying.” One time a pupil shouted at him, “Hey teach, ever try to fight 35 kids at once?!” He would quit before the end of his first semester.

“Drama Of Teenage Terror”

Hunter’s semi-autobiographical novel was a sensation when it was published in 1954. It was a time in the US when the country believed itself under the threat of hostile forces, of Communists, of people of colour, of intellectuals, of music, of the young. Blackboard Jungle taps into that fear and paranoia, while also attempting to make sense of it. Only the novel’s more noble concerns were barely acknowledged, most reviews painting a picture of the book as a savage exposé of youth gone feral, with one Time critic warning it would “scare the curls off mothers’ heads and drive the most carpet-slippered father to vigilant attendance at the PTA.”

The movie, when it arrived, proved equally disquieting. The film’s makers, MGM, billed it as a “Drama of Teenage Terror”, while the trailer described it as “fiction torn from big-city, modern savagery”. Newspaper ads, meanwhile, roared “They Turned A School Into A Jungle!”

Glenn Ford, then most famous for his role in the 1946 noir classic Gilda, was cast as the movie’s protagonist, a war veteran embarking on his first teaching job at North Manual Trades High School (its exact location is kept vague). “This is the garbage can of the educational system,” a fellow teacher tells Dadier. “Don’t be a hero and never turn your back on the class.”

From here on, the movie treats its young characters as figures of terror. A school assembly appears on the cusp of a riot. When Dadier introduces himself to the class, one of them throws a baseball at the blackboard, breaking its surface. Later, a group of thugs trash a music-loving teacher’s collection of jazz 78s. North Manual Trades High School, we’re meant to think, is a lawless institution, where students run amok and teachers have given up.

Classroom Clash

The school is a racial melting pot – African Americans, Puerto Ricans, Italian Americans, Irish Americans… And, to the film’s progressive credit, it’s a Black character that is shown as the one with the most potential. Gregory Miller would be the breakout role for Sidney Poitier and he radiates charisma as the disruptive, but undeniably gifted musical prodigy. Less developed are many of his fellow classmates – Vic Morrow comes across as a cut-price Brando as the flick knife-flaunting Artie West and there’s little for Jamie Farr, later to find fame in the small screen version of M*A*S*H, to sink his teeth into.

Ford, however, is the linchpin. He’s masterfully understated as the put-upon, but dogged Dadier, who begins with lofty ideals, has them challenged after being beaten up, and then has his faith in the education system restored as he wins over his unruly students.

Adult audiences, then, went away calmed by Blackboard Jungle. Sanity prevailed in the film’s final moments, just as good won over evil in horror flicks, and Communism in 1950s movies was always beaten by good old American values.

“There was a lot of turmoil going on, and it brought teenage angst-filled young people to the fore, it was quite edgy,” Ford’s son Peter told the Calgary Herald in 2015. “It celebrated and brought to the attention of the world that there were teenagers and there was this culture of youth that up to that time had not been considered.”

Rockin’ Rebellion

It was actually Peter Ford that helped the film capture the zeitgeist. It’s debatable whether we’d still be talking about Blackboard Jungle had its opening music been something written by an in-house tunesmith. But kicking off with the red-hot sounds of Rock Around The Clock made it absolutely of-the-moment. Today, it would be like launching a film with a blast of death metal or grime, so startling that music would have been to anyone over the age of 20. And it was all down to Glenn Ford’s 10-year-old son.

“I loved R&B, or ‘race music’ as it was formally known,” Peter told FilmTalk in 2017. “My mother was raised on the stage working with Black performers as early as the 1920s, and she understood and encouraged my interests.”

It was only when the film’s producer Pandro S Berman – who was visiting the Fords – heard Peter spinning the B-side of Haley’s Thirteen Women (And Only One Man In Town) that he realised he’d found his theme song. MGM swiftly purchased the rights for $5,000.

Youth Gone Wild

It was doubtless the inclusion of Haley’s era-capturing classic that helped the movie at the box office. Brooks may not have intended the film to be a ‘youth picture’ like the similarly provocative The Wild One or Rebel Without A Cause, but the teenagers flocked to it.

“Suddenly, the festering connections between rock and roll, teenage rebellion, juvenile delinquency, and other assorted horrors were made explicit,” wrote critic Greil Marcus in 2014. “Kids poured into the theatres, slashed the seats, rocked the balcony; they liked it.”

Too much, it seems. When it came to the film being considered for release in the UK, the British Board Of Film Classifications were initially of the opinion that it was too incendiary to be shown. After all, they had banned The Wild One, calling it “a spectacle of unbridled hooliganism”.

Though they wrote that they considered the movie “well-made and well-acted”, the Board’s president Sir Sidney Harris was of the opinion that it couldn’t be released, with his deputy Arthur Watkins saying the BBFC would not pass any film “dealing with juvenile delinquency or irresponsible juvenile behaviour” unless the morality of the movie was “sufficiently strong and powerful to counteract the harm that may be done by the spectacle of youth out of control”.

I’m Not A Juvenile Delinquent

Following protestations from the film’s UK distributor, the BBFC reconsidered its position, and it was eventually passed, albeit with significant cuts and slapped with an X certificate. By 1994, when the film was released on home video, it was deemed uncontroversial enough to be put out uncensored, with a 12 certification.

Blackboard Jungle has never been formally remade, but there’s many films since that have mimicked its premise. To Sir, With Love, made 12 years on, would cast Sidney Poitier as the teacher in charge of a class of riotous British schoolchildren, while movies such as Stand And Deliver (1988), Renaissance Man (1994) and Dangerous Minds (1995) are remakes in all but name.

Visceral Power

Yet none of those had the impact of Blackboard Jungle. None of them ever had an American diplomat – in this case the US Ambassador to Italy – trying to stop it being shown at a film festival because it portrayed their home country in a poor light. And none of those imitators have been selected for preservation in the US National Film Registry for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”.

Time can make even the most inflammatory movies of their day seem as tame now as a Doris Day rom-com, but Blackboard Jungle still possesses a visceral power. And that’s what makes it as potent in 2025 as it was in 1955.

Featured image credit: Herbert Dorfman/Corbis via Getty Images

Subscribe to Vintage Rock here