Their recorded output was limited, but for a short period Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers electrified the 1950s rockin’ scene…

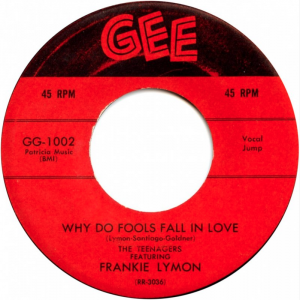

Some argue that Why Do Fools Fall In Love is the greatest of all doo-wop songs. It’s a bold claim in the light of the competition. No sub-genre of pop or rock music has yielded so many unforgettable one-off classics as doo-wop, countless songs that are instantly recognisable even if you can’t name who sang them.

Love is a rare example of a song sung by a juvenile that rises above novelty value to become a sublime piece of pop. Frankie Lymon’s vocal glides and soars with the beauty of a songbird in full flow. It speaks to adult listeners today just as it entranced teenagers back in 1956.

Angels Of Harlem

Sadly, Lymon was to be another early rock casualty. Only 13 when the song propelled him to stardom, the New Yorker would be dead by the age of 25, his career having long since hit the skids.

However, despite their limited output, Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers were no one-hit wonders. In a golden run from the start of 1956 to the summer of 1957, they cut a slew of Top 10 R&B smashes, several of which crossed over to the Billboard Top 100 (*note pre ‘Hot 100’ era in the US). They were also hugely popular in the UK, with three of their discs reaching the Top 30.

Like most doo-woppers, Lymon was an unschooled talent, but music was in his blood. His truck-driving father sung in a local New York gospel group, The Harlemaires. Frankie and his brothers Lewis and Howie had formed their own stoop-singing group, The Harlemaire Juniors, in between leading a hardscrabble life on Harlem’s streets.

Why Do Fools Fall In Love

Aged 12, Frankie hooked up with some slightly older youngsters in the district, Herman Santiago and Jimmy Merchant (both tenors), Joe Negroni (baritone) as well as Sherman Garnes (bass), who were entering talent shows as The Premiers. A mixed-race group, at this stage Frankie was singing first tenor to the Puerto-Rican Santiago’s lead vocal. Generally doing standards, after they were advised to generate material of their own, they began working on a ballad they initially called ‘Why Do Birds Sing So Gay?’

Richard Barrett, lead vocalist of respected New York group The Valentines, was sufficiently impressed to coach them before bringing them to the attention of George Goldner, who had been releasing The Valentines’ songs on his Rama label. Goldner was selling to the Latin market via another of his labels, Tica, and together with Santiago and fellow Puerto Rican Joe Negroni in the line-up, The Premiers had an obvious attraction for him.

But at their audition he quickly spotted the special appeal of Lymon. After some more coaching from Barrett, Goldner signed them up, allocating them to another of his labels, Gee, so-named after the hit song of another group on his roster, The Crows.

Teen Spirit

The Premiers’ first recording session took place in New York’s Bell Sound Studios in 1955, backed up by tenor saxophonist Jimmy Wright’s session band. Their main song had long since developed from a ballad into something at the more rocked-up end of doo-wop, with Why Do Fools Fall In Love now its title.

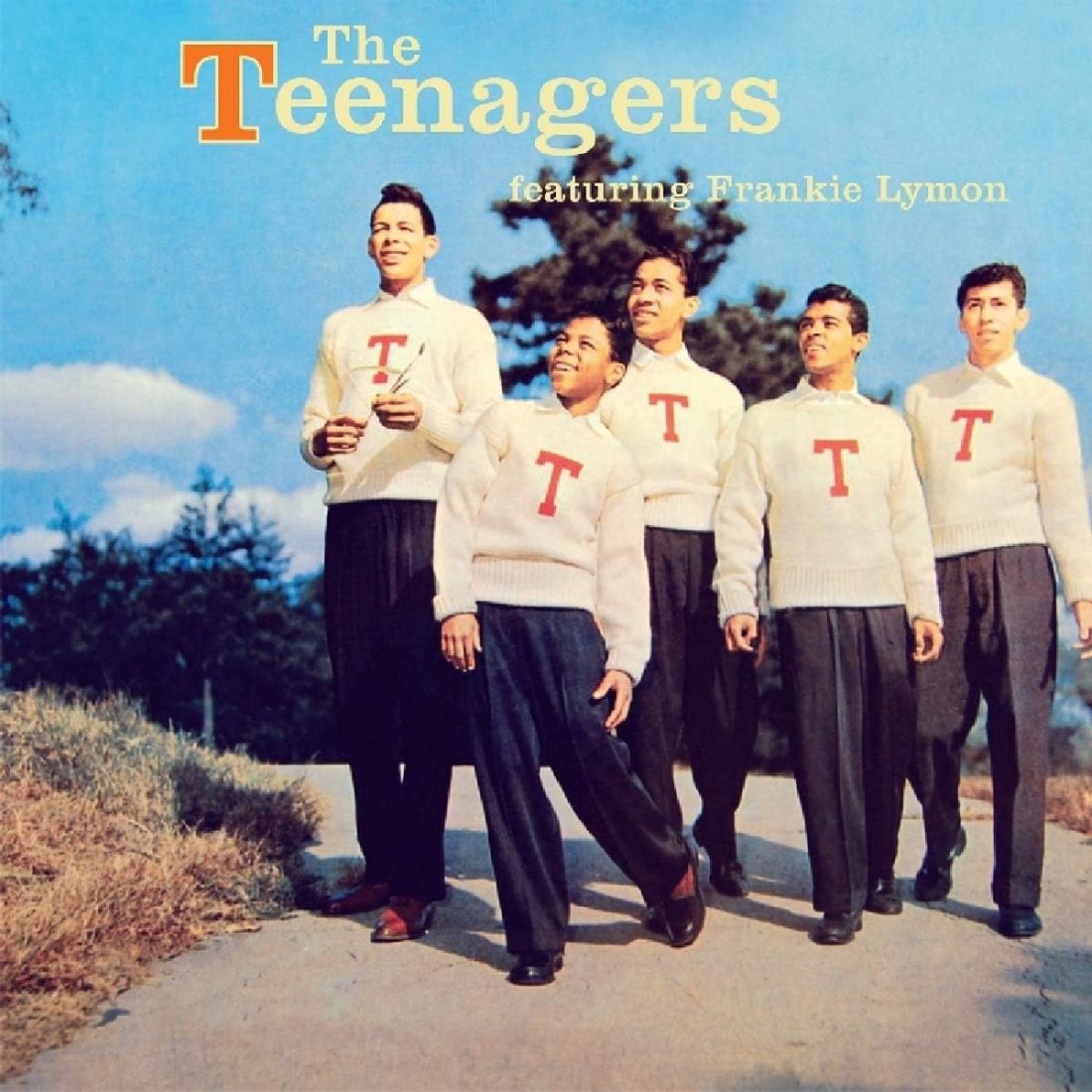

Lymon had been given the lead and Herman Santiago moved to first tenor – though an alternative story maintains that Santiago had a cold on recording day, and Lymon deputised. At the session, Wright, who would do the arrangements for all of the group’s Gee material, suggested that they change their name to The Teenagers. When the record was finally released at the tail end of 1955, the name on the pressings read “The Teenagers Featuring Frankie Lymon”.

With Billboard magazine forecasting a crossover hit, sales quickly took off. Despite predictable attempts to cover it, the platter saw off all of the contenders, topping the R&B chart and rising to No.6 on the Pop listing. Very obviously, this was a teenage song sung by teenagers, and there were detractors. “Regretfully, this effort must be an inspiration to all writers of rubbish,” sniffed a reviewer in the NME. That didn’t stop it holding the No.1 spot in the UK for three weeks.

Youthful Harmony

The excellent follow-up was I Want You To Be My Girl. Listening to Lymon’s individualistic vocal stylings on the track, it’s easy to understand how he was such an inspiration not just to other high-voiced male soul stars such as Little Anthony and Smokey Robinson, but also female pacesetters including Ronnie Spector and Diana Ross. Featuring a fine sax solo from Jimmy Wright, the single was another deserved crossover hit, reaching No.13 in the US. Lymon delivered another strong vocal for the B-side, I’m Not A Know It All.

Next up was the less successful pairing of Who Can Explain?, a too obvious attempt to replicate Why Do Fools Fall In Love and the Jimmy Castor-penned I Promise To Remember, which was regulation doo-wop, albeit with Sherman Garnes’ intriguing bass intro, “Hoolie-bop-a-cow-bop-a-cow-bop-a-cow-cow.” But while that single only made Billboard’s No.57 (and R&B No.10), the superior follow-up, The ABC’s Of Love, only made No.77 (No.8 R&B). Perhaps Goldner should have gone with the B-side. While The ABC’s Of Love was a fun jump number, the gorgeous flip Share was doo-wop at its most romantic and ethereal.

I’m Not A Juvenile Delinquent

Both I’m Not A Juvenile Delinquent and Baby Baby were recorded for Alan Freed’s 1956 film Rock, Rock, Rock!, but released on a single before the movie premiere. Despite being heavily pushed by Freed on his radio shows, the single did not chart in the States.

The British response was more favourable, the two sides making No.12 and No.4 in their own right in the early months of 1957. Shakin’ Stevens And The Sunsets thought enough of I’m Not A Juvenile Delinquent to include it on their second album, I’m No J.D.(1971). Arguably, Baby Baby was structurally the more interesting song.

The success of the two sides in Britain was attributable to the group arriving for a three-month tour in March of 1957, opening their set on the first night at the Liverpool Empire with I’m Not A Juvenile Delinquent. The group were always fine value as a live act, being hyper-animated; Frankie and Herman were especially lithe and acrobatic. In their first months of fame in the States they’d played top venues such as Brooklyn’s Paramount and the Apollo in Harlem. In Britain, they played the iconic London Palladium for a fortnight, unprecedented for an outfit of their type.

Hidden Discord

Unfortunately, while their public image was one of sweet innocence, the reality was somewhat different. The group was always shockingly exploited by their management. Lymon’s schooling was sacrificed, while his precocious taste for older women and drugs was far from sweet and definitely not innocent. On the British tour other members of the group were infuriated by the approach to promotion, which seemed to focus entirely on the now 14-year-old Lymon.

Worse, with Goldner reckoning Lymon had the pipes and charisma to be pushed as a solo pop act, he went into the studio to record without The Teenagers, backed by an orchestra. Goody Goody, a swinging standard, apparently had the Ray Charles Singers providing the vocal backing, even though the single was still issued under the name of Frankie Lymon And The Teenagers.

It charted at No.20 in the US and No.24 in the UK. The last authentic recording by the group to make the R&B chart was the beautiful Out In The Cold Again. By summer 1957, Goldner had moved Lymon to his Roulette label where he would record, largely unsuccessfully, without his old but now estranged pals.

Tragic Ending

There was one final coming together as an act to perform two tracks – Love Put Me Out Of My Head and Fortunate Fellow – for another Alan Freed film, Mister Rock And Roll. Goldner deemed the material not good enough to put out on a single. To be fair, with such a voice, Lymon was always destined to venture beyond the frontiers of rock’n’roll. But his attempts for Roulette didn’t sell, and Goldner soon had him back singing rockin’ material. A new version of Thurston Harris’ Little Bitty Pretty One charted for him in 1960, but at 18 his voice was losing its childlike charm.

Without Lymon, The Teenagers faded away, but their former leader’s descent was tragic. He developed an addiction to heroin. As the gigs dried up, he was scrounging money off strangers to buy drugs. He did rally, and seemed to have taken back control of his life and been on the point of a comeback. But succumbing to the needle once more in early 1968, Lymon overdosed and was found dead on his grandmother’s bathroom floor.

Subscribe to Vintage Rock here