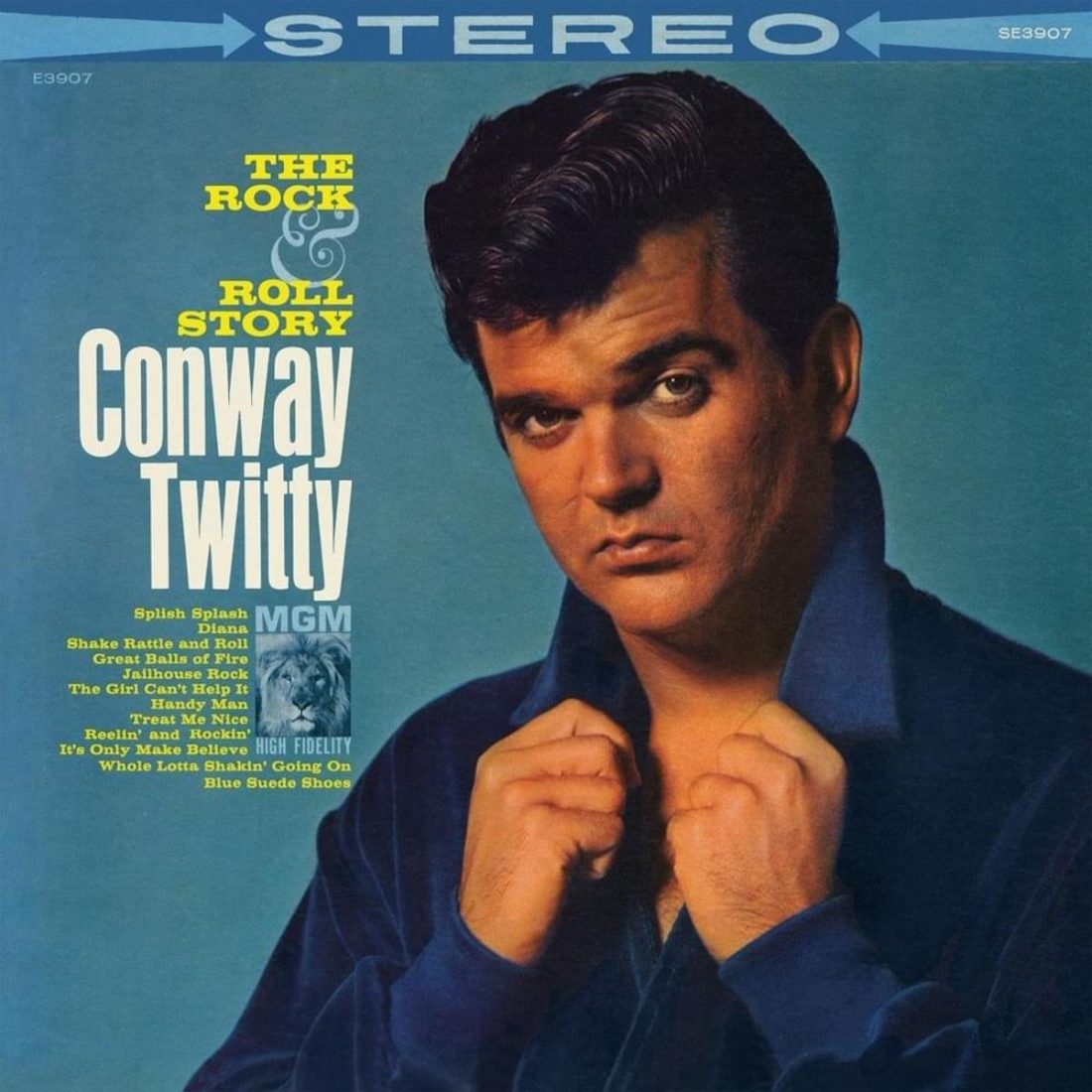

The later career of Conway Twitty elevated him to The High Priest Of Country Music, but before that he was a highly capable rockabilly, with a knack for releasing compelling rock-outs of old songs…

Features about rock and pop stars tend to fall into two categories. There are the ones about the accepted greats, where no superlative is too extreme. And there are the ones about the underrated performers, many of them overlooked during their performing careers. Conway Twitty – real name Harold Jenkins – belongs in neither category.

Twitty was an artist who took what relatively average talent he had and squeezed it for every drop of success it could yield. He did some good, if not particularly original, Elvis-style rockabilly and co-wrote one of the all-time great rockaballads It’s Only Make Believe – a smash cross-Atlantic hit. Glen Campbell would, of course, really give this great song the full kitchen sink treatment that it deserved a few years later.

Then he became massive on the country scene, the arena in which, despite initial scepticism within the country community, he claimed his heart always lay. The quality of his country material, as with the rock’n’roll, was variable, but included a series of immensely popular duets with Loretta Lynn. He built a huge business empire on the back of all this, including the Nashville theme park, Twitty City. His only bad luck was suffering a stomach aneurysm in 1993 on the way to a show, resulting in his shock death at the age of 59.

Wilde About Twitty

Yet Twitty was – and remains for many – a revered figure, not just among legions of, largely female, country fans, but also within the rockin’ community where he still has some distinguished admirers. Interviewed at his home in Surrey in 2018, somewhat surprisingly, Marty Wilde admitted to disliking the sound of his own singing voice, and then started talking about Conway Twitty. He reckoned one of the most underrated tracks he’d ever heard was Twitty’s Make Me Know You’re Mine, recorded in Nashville in 1958. “That was one of the greatest rock’n’roll songs ever made,” Wilde stated. “I worked with him. He was obviously influenced by Elvis, but he had his own style all right. That record – I’d give anything to sound like that. That’s the kind of voice I would like to have had!”

It’s the Twitty rasp that’s so appealing on his most hardcore rockabilly songs. There’s a gravelly, deep-voiced, over-the-top quality and, on these tracks at least, you forget about any perceived Presley-derived mannerisms. It’s been written that Twitty was better at ‘slow-burn’ than ‘red hot’, but the preference here is for the frantic material, the likes of Shake It Up and the brilliantly raggedy takes on Danny Boy and Mona Lisa, than for Wilde’s favourite Make Me Know You’re Mine or the obviously derivative Long Black Train.

Rockin’ The House

Harold Jenkins was one of many Southern country boys who turned to rock on hearing Presley. Born in Friars Point, Mississippi, in 1933, on the Arkansas state line, but only about 40 miles west of Elvis’ hometown of Tupelo, he had formed his own band and performed country music as far back as the 1940s. But he had also nurtured hopes of becoming a baseball player, until his US army draft in 1953 led to a two-year stint in the Far East.

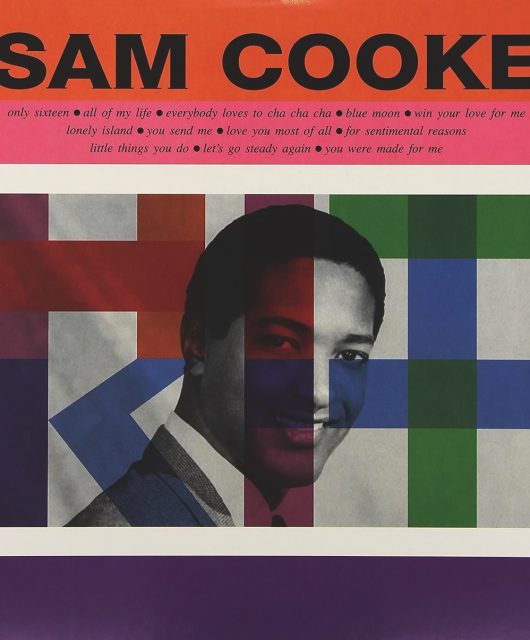

However, on his return to the States, hearing Presley’s Mystery Train for the first time reignited his interest in performing music. Still going by his birth name, he formed a new band which he called the Rockhousers and worked up a signature song for them called, naturally enough, Rock House. Then he headed for Memphis’ Sun Studio to audition for Sam Phillips. “The studio was like a hole in the wall, but it looked like Radio City in New York to us,” Twitty later recalled to Colin Escott.

Unfortunately, Phillips didn’t take to Twitty, believing him to be too much of a Presley soundalike, but although there were some wild demos of self-penned material like Give Me Some Love, he never did get a Sun release under his own name. Yet Phillips did like Rock House. Jenkins had cut a primitive, suitably frantic demo of the song before he’d arrived at Sun, but it was Roy Orbison who got the Sun outing, complete with classic slapback echo effects, released in September 1956.

Shakin’ Things Up

And so, altering his name to Conway Twitty, (the names ‘Conway’ and ‘Twitty’ were sourced from the towns of those names in Arkansas and Texas), he moved on for a short-lived stint with Mercury Records.

At that time Mercury was sharper on pop than rock, so Twitty’s records didn’t get much of a push, but while first single, I Need Your Lovin’, was basically another go at Give Me Some Love, the follow-up Shake It Up paired with the solid R&B of Maybe Baby – both Twitty originals – lacked nothing for effort.

Very few white rockers of the time sounded more het up than Twitty on Shake It Up, except perhaps Sonny Burgess, and there was suitably deranged sax, pounding drums and a rough guitar solo. The second sax break was a blatant lift from Bill Haley’s version of Shake, Rattle & Roll and the vocal group nicked Little Richard’s “ah-wop-bam-a-loom-a-ah-wop-bam-boom” for their repeated refrain.

Land Of Make Believe

Fortunately, success lay just around the corner for Twitty at MGM. By now, multi-instrumentalist Jack Nance, previously the drummer with Sonny Burgess and The Pacers, along with Pacers guitarist Joe Lewis, had joined Twitty’s band (Burgess himself would later join the road band). Nance helped Twitty write It’s Only Make Believe, and they recorded the song in Nashville backed by ‘A-Teamers’ like Grady Martin, Ray Edenton, Floyd Cramer, Lightnin’ Chance, along with vocal backing from The Jordanaires, in the spring of 1958. MGM actually put it on the B-side of Twitty’s I’ll Try and at first the single made little impact until a DJ in Columbus, Ohio, flipped the disc and started playing the bottom side. Suddenly interest skyrocketed.

Twitty found himself with a No.1 record both in the States and the UK, leading to TV appearances on such programmes as the The Andy Williams Show and being whisked across the Atlantic for a couple of slots on Jack Good’s Oh Boy!. Apparently, some people thought it was Elvis singing It’s Only Make Believe. Perhaps that was what helped it sell eight million copies worldwide. It was certainly in the mould of those power ballads that The King brought off so well.

Twitty’s other big US hit was Lonely Blue Boy, which was rewarded with a No.6 Billboard placing a couple of years later. This was an example of the ‘smouldering’ Twitty that some people have raved about. Others include Make Me Know You’re Mine and Is A Blue Bird Blue? But he actually did some fantastically raving covers of standards that were at least as exciting.

Beat Rocker

In fact, few rockers had such an uncanny knack of updating oldies for the beat market. Certainly, American record buyers went for his riveting Danny Boy (a Top 10 hit in the US) which, when you think of the morbid lyric about death, (based on the traditional song Londonderry Air), was a pretty irreverent, bad-taste record for its time. He starts the song off in traditional style, before leaping into a belting rocker, a far cry from the sober sentimental approach commonly taken to the song by artists of the day.

Twitty would also have a hand in what proved to be one of the last Sun hit records, Mona Lisa. There were also great takes on My Adobe Hacienda, Trouble In Mind, Blue Moon and Pretty Eyed Baby. He was well placed to follow in fellow good ole’ Mississippi Delta boy Fats Domino’s footsteps and do another cracking version of the 1940s song Blueberry Hill, with richly exaggerated Old South elocution (“Ma heart stood sti-i-yaa/ right dere on Blueberry He-yaa!”). Unchained Melody, the subject of so many watery interpretations over the years, was given a fabulous schizoid reading by Twitty, crooning his way conventionally through the first part of the song, before slipping the gears and going into an incredibly soulful growl.

Add to that list Twitty originals like Hey Little Lucy! (Don’tcha Put No Lipstick On), which caught him at his insolent best, and Heavenly, on the flipside of Mona Lisa and sounding a little like It’s Only Make Believe, and you have to conclude that Marty Wilde was right. Conway Twitty, in his rockin’ days, had his own sound alright.

Subscribe to Vintage Rock here

Read More: When Rockabilly Shook The World