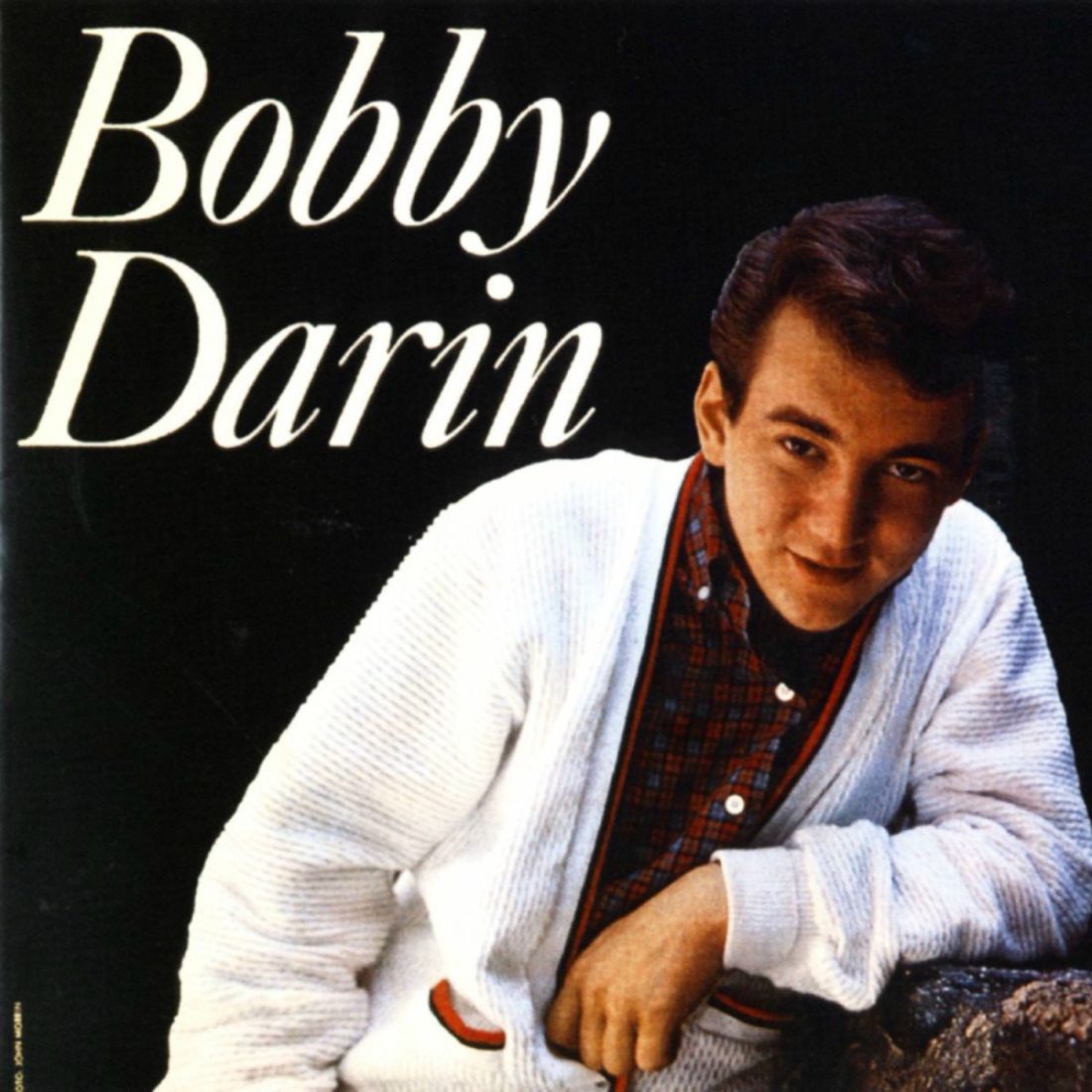

It’s no surprise the multi-faceted songs of Bobby Darin have been such a hit in Hollywood – his own too-short life story sounds like it was straight out of a movie script.

David Burke tells the tale…

American cultural icon Dick Clark once described Bobby Darin as “a musical chameleon” who could effortlessly traverse a multiplicity of genres, from heavy-duty rhythm and blues, through finger-snapping swing and torchlight balladry, to radical folk and hip rock’n’roll. And while the versatility that defined him could be as frustrating as it was fascinating, arguably Darin’s protean artistry is perhaps best understood in the context of a life plagued by health problems which began in childhood and led to his premature demise at just 37 years old.

To deploy the somewhat trite language of melodrama, the diverse nature of Darin’s career seemed to symbolise a race against time, a recognition of his own sense of mortality. “He was always anxious to do it all,” said Dick Clark. “He was driven.”

East Harlem Roots

Darin was born Walden Robert Cassotto into a tangled web of family secrets in New York in 1936. His father, Saverio, a small-time hoodlum, had died in prison before his birth, while his mother, Vivian Walden, came from a wealthy Chicago mill-owning background. More than three decades later, Darin would learn the shocking truth about his lineage – the woman he called mom was actually his grandmother, and his real mother was his sister, Nina. He never found out the identity of his father. The reasons for this deception, which had a profound impact on Darin when it came to light, remain unclear, though the shame of Nina’s teenage pregnancy as part of a Catholic community might have been a factor.

Darin was a sickly boy. He suffered the near-fatal first in a series of rheumatic fever attacks aged seven. Doctors didn’t expect him to live long. Even after his recovery, Darin, too weak to walk, became an object of ridicule. According to anecdotal recollections of this period, neighbours would taunt Vivian as she pushed him around the block with cries of, “Whaddya wanna wheel that thing around for? It’s gonna die!” The singer’s own memories are of spending a lot of time “being in bed, stiff, hurting. I used to read or do colouring books. I couldn’t do what everybody else was doing.”

However, neither he nor Vivian would allow his condition to inhibit his ambition. By the time Darin passed the rigorous public entrance examination for the Bronx High School of Science, he was proficient on several instruments, among them piano, drums and guitar.

Making A Splash

Darin soon made fast friends with Don Kirshner, an early composing partner. The pair wrote and performed commercials for a New Jersey radio station, and cut some demos. “I was the lyric writer, he wrote the melodies – but he was the talent,” said Kirshner. One of their compositions came to the attention of Connie Francis’ manager, George Scheck, who secured Darin a contract with Decca, though his tenure on the label was a succession of failed singles, including a version of Rock Island Line, a hit for Lonnie Donegan.

Following the termination of his Decca deal – and his turning down Capitol Records because they wouldn’t meet his royalty demands – Darin went to work at the Brill Building on Broadway, a proving ground for pop songwriters, and signed on for one year with Atco Records, a subsidiary of Atlantic. The story goes that Atlantic chief Ahmet Ertegun heard him playing “some terrific things” on piano in the office next to his, and got Darin onto the end of a session already booked for jazz chanteuse Morgana King. “History might remember what Morgana King did on that date, but I certainly don’t. Bobby did Splish Splash and we were off to the races,” Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler recalled.

Released as a single, Splish Splash, on which Darin shared the credit with DJ Murray Kaufman, shifted more than two million copies and peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100. Further minor hits followed with Early In The Morning (a hasty rewrite of Ray Charles’ I Got A Woman) and Queen Of The Hop – singles on which, according to close friend Dion DiMucci, Darin “knew how to rock, but also knew how to have fun with it” – before Dream Lover provided him with another big seller.

Dream Lover

Neil Sedaka, another Brill Building alumnus, played piano on that hit in 1959. “I remember it well. They were losing the feel of Dream Lover, not happy with the way it was going. He asked me to sing harmony, a third above, and I believe there’s a copy of that version somewhere in the Atlantic library. Then I suggested they put the guitar part up an octave, and I believe that enhanced the record.”

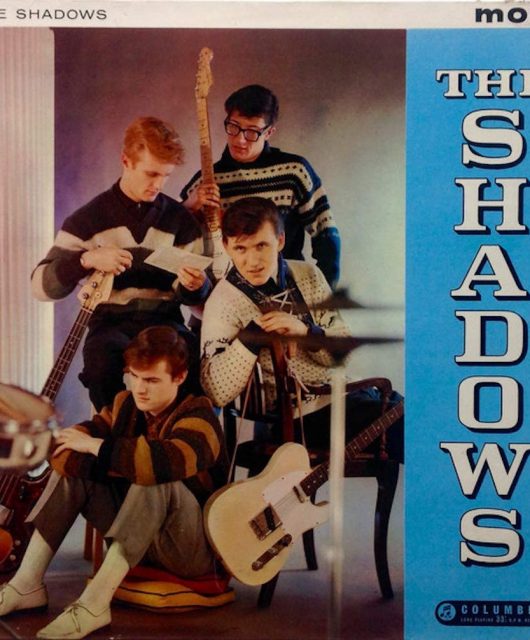

Record buyers obviously thought so, too, as Dream Lover made it to No. 2 in the US and top spot in the UK. But by the time Darin crossed the Atlantic for his first British tour to share a bill with Duane Eddy and Clyde McPhatter in 1960, he had already moved on musically into pseudo-Sinatra territory, taking Mack The Knife to No. 1 in both countries and Beyond The Sea into the upper reaches. It made for an uncomfortable experience on the opening night in London. His manager, Steve Blauner, remembered the Teddy Boys in the audience giving Darin a hard time.

“Even though I wasn’t necessarily thrilled with the music, Bobby was hot. But the Teddy Boys wanted to see him do rock’n’roll. There was a point where he took a chair, straddled it for stage effect and sang My Funny Valentine. And they started to make noise. It was really embarrassing. There was a part of the crowd that tried to quiet them, and the other part egged them on. It was unbelievable. I went backstage and Bobby lashed out at me.”

Talented Performer

Back home, Darin found himself playing Las Vegas, down the street from Sinatra’s Rat Pack, and smashing attendance records at New York’s Copacabana. As his fame increased, there were movie roles, too, including in the romantic comedy Come September, and Captain Newman M.D., for which he received an Oscar nomination.

And still the hits kept coming – You Must Have Been A Beautiful Baby, Multiplication and What’d I Say – before Darin quit Atco on a high with Things and finally joined Capitol.

This era marked a new phase in his journey as he explored new idioms. Roger McGuinn, later of The Byrds, was playing guitar in The Chad Mitchell Trio when Darin – who saw the group do a support slot for comedian Lenny Bruce on the Vegas Strip – hired him. “After our set Bobby came backstage and said that he liked my playing,” said McGuinn. “He explained that he wanted to add a folk segment to his show and wondered whether I would like to back him up on guitar and sing harmony.

“I played on some sessions around the [album] 18 Yellow Roses time. I’m not sure what songs I’m on. Live, Bobby would sing his hits for about 15 minutes, then he’d take off his tie and bring me out. We would do three songs with the rhythm section and my 12-string guitar and harmony. After I left the stage, he would sing standards. He was an excellent singer and instrumentalist. Bobby taught me a showbiz ethic that’s hard to find these days. He was extremely professional. He was always well groomed, in tune and on time.

“He commanded a great deal of respect from everyone. I learned many valuable lessons from him during the two years we worked together. It was an honour and a privilege to have worked for such a great and talented performer.”

Folk Hero

Darin immersed himself deeper in the folk scene as a social and cultural revolution surged through America in the 60s. For a while, he was making music that mattered, even if the hits – with the exception of Tim Hardin’s If I Were A Carpenter – had largely dried up. The entertainer morphed into the protester on Simple Song Of Freedom and Long Line Rider. When prohibited from performing the latter on The Jackie Gleason Show, Darin walked off set.

He addressed an anti-Vietnam demonstration at City Hall in Los Angeles and took out newspaper ads denouncing the US invasion of Cambodia. An early supporter of Dr Martin Luther King and the struggle for civil rights, participating in the freedom march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, he also threw his celebrity weight behind Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 1968. “Darin was very close to Bobby Kennedy,” said Steve Blauner. “In fact, they were up in Seattle right before he was killed. On the plane Kennedy would come over to him and say, ‘Sing my favourite song’ – it was Blowin’ In The Wind – and Bobby would take out his guitar and play it.”

Difficult Time

He last saw the candidate the day before Kennedy was murdered at the Ambassador Hotel in LA on 5 June 1968. “He was very tormented in the wake of RFK [being shot],” claimed Darin’s son, Dodd. “He went nuts, essentially, when he heard the news. That was a very hard time. It began a process of introspection about everything he did, what he stood for. He went to Big Sur, lived near the beach in a little trailer, ran his own electricity, did woodwork, had very little to do with the showbusiness world and tried to find out what was important to him.

He sold a lot of his possessions, gave a lot of stuff away and was trying to make a change. Nobody really knew who he was; he got his mail under the name ‘Cassotto’, drove a little Toyota. Basically, he just dropped out to take stock. It was his hippie period, a time to re-evaluate, but not something driven by fad or style. The RFK thing was devastating. I guess, clinically, he was probably depressed. It was a very difficult time.”

Darin established his own imprint, Direction Records, declaring that it was his mission “to seek out statement-makers”. He made his own statement with Direction’s debut, Bobby Darin Born Walden Robert Cassotto, “designed to reflect my thoughts on the turbulent aspects of modern society”.

The Great Believer

As the 60s segued into the 70s, Darin’s health deteriorated. He underwent open heart surgery in 1971 to have plastic valves inserted, and returned to the showbiz treadmill within six months, signing to Motown Records, playing bit parts on the small screen in Ironside and Night Gallery, and even hosting the NBC variety series, The Bobby Darin Show.

But it didn’t take long for those in his entourage to notice the post-operative optimism evaporating – walking up steps was a chore and Darin was often listless during rehearsals, forgetting things, repeating others.

“To me, it had gotten bad,” said Steve Blauner. “It was like he was senile. He’d be walking down the street and walk into the wall. He didn’t drink, he didn’t do drugs. He once took Dodd into West Hollywood to buy a bike and he told him he’d be right back. He never came back. He forgot. That’s how bad it was. It was just awful.”

Darin kept an oxygen tank in his NBC dressing room. Geoff Edwards, a regular on the show, would sit with him in there. “I would say something and he would say – taking a deep breath – ‘Yeah, that’s funny’, and take another deep breath. He was not a well guy.

“The last show we did was with Peggy Lee and they were standing on two podiums. Bobby would sing and they’d go to break, and he would drop his head down with his chin on his chest and his hands down and just stand there like that until they were ready to come up, and then they’d be back on.”

The Fading Star

Dodd Darin was in Vegas for his father’s last performances in August 1973. “He talked about Elvis, who was opening the next night. He joked, saying, ‘I look out there and see the room half-filled and I cry, because tomorrow night, I know the rafters will be filled. But Elvis is the king’. He was very melancholy, very emotional. He was very ill. But you never knew that when he worked. And he would never let anyone know. After the show, he’d make sure he had it together before he’d greet people. He was very concerned that people not realise how sick he was.”

Darin had a “decent relationship” with Elvis, according to Dodd. “They used to see each other. They would have a bite to eat and they were kind of friends. But they were two very different people. My dad was kind of uptown and kind of intellectual. Elvis was different, a simpler guy. But yet they had good relations. And in fact, Presley had mentioned that my dad was one of his favourite singers.

“There’s a disparity in recognition, obviously. But I think he’s been under-appreciated. He’s just not gotten the credit he was due.”

Tragic End

On 11 December 1973, Bobby Darin checked himself into Cedars-Sinai Medical Centre in LA for another round of open heart surgery to repair the artificial valves. He died on 20 December, despite the efforts of doctors who battled for more than six hours to save him.

“They couldn’t put him in a niche,” said Neil Sedaka after Darin’s passing. “He even equalled some of the Sinatra records. He didn’t have the drama and the tragedy that Sinatra went through, but we all knew that his time would come.”

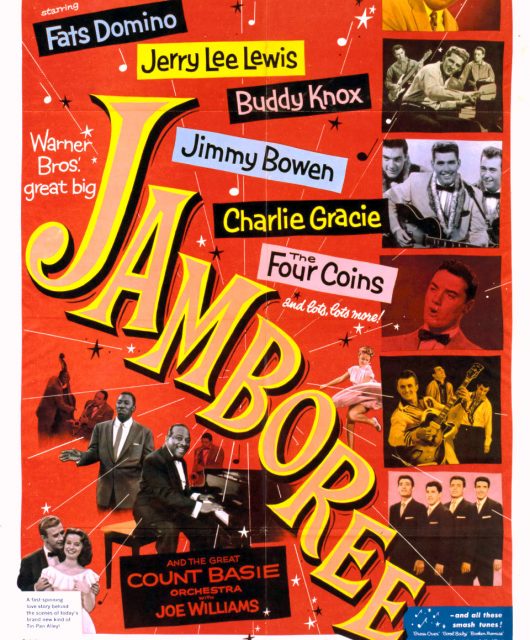

For Steve Blauner, Darin understood Al Jolson, Bing Crosby, Dion and Fats Domino. “He couldn’t stay in one place. If he did it, he believed it. Bobby did rock’n’roll, he did the American songbook, he did country and western and he had his protest time. And no matter what he did, he did really great.”

Subscribe to Vintage Rock here